Banko has been gone three weeks.

When I worked at the Young Women’s Freedom Center, not hearing from a young person for three weeks was worrisome. We’d check in with as many friends as we could, frequent the areas we knew they hung out at, even go to wherever they were staying… that’s all useless at this moment.

Someone has permanently taken a life from our community. They are not coming back.

When I think about the why, I get enraged.

This was completely preventable. Completely.

In the last three weeks, I have learned more about MY OWN ideas of justice than I have in all 46 years of my life. There is something so different about experiencing a young person, a light in the world, go out and know that it was because no one was willing to give him the one thing he knew would save his life. Housing. A place where he could create his own safe haven, fill it with pictures of his family, invite folks over to break bread—have a space to make bread.

I have been moved by the amount of love and support Banko is receiving. It’s overwhelming. This has actually been the most support I have seen in a long time for an individual in San Francisco. At first, I thought it was because Banko was a young person, 24. But actually, it’s because people deeply understand the need for housing and the plight of struggling to survive in the city you were born and raised in.

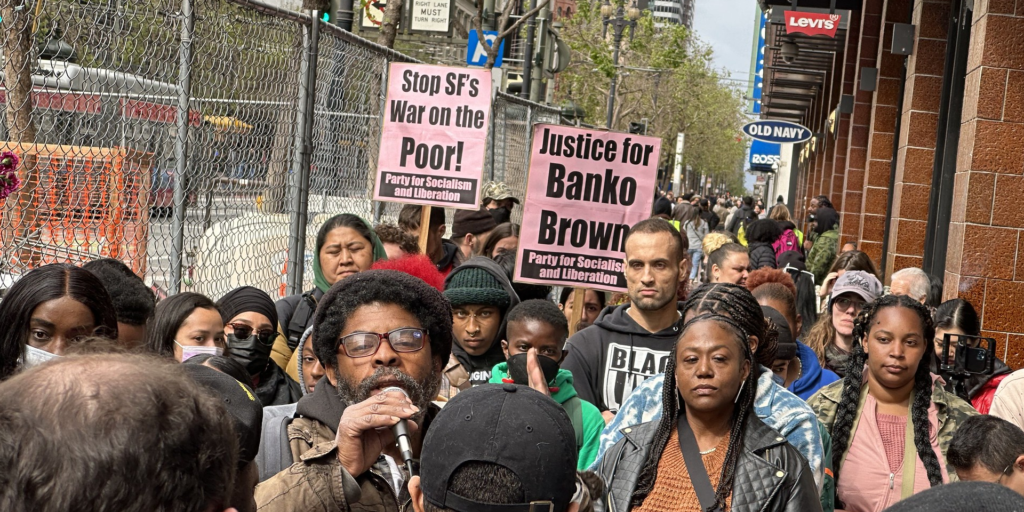

This rage is deep for so many of us who know it should not be this hard to live in your city. This support has grown nationwide since the video was released. I was brought to tears seeing a young boy at a rally for Jordan Neely in New York with a sign that said “Justice for Neely, Justice for Banko, Justice for Me.”

But “justice” is subjective and is shaped by people’s previous experiences with justice.

Right now, the “justice” being demanded is a prosecution of the armed guard who shot Banko, which requires a push for our state attorney general Rob Bonta to take this off the hands of SF’s District Attorney Brooke Jenkins, who has shared numerous times with the public that she is not prosecuting the security guard.

At the core of this demand is a request for the harm doer to be held accountable for his harm doing in a court of law and take on the consequences of incarceration for these actions.

Anytime I see a demand for prosecution, I am brought back to my time at the Community Justice Network for Youth and visiting a family with RJ Circle Master Cheryl Graves in Chicago. It was with a mom whose son was killed by his friend for getting his sister pregnant. All of them were childhood friends and it divided a three-block village that watched these young men and woman grow up since they were children.

I remember her sharing that all she wanted, in the beginning, was for this young man to go to jail, that it was all the pain in her heart allowed for her to think about. Once he was convicted, she felt so bad. She couldn’t believe she wanted someone to go away to rot in a cell. She thought about her grandbaby that didn’t have their dad or their uncle now. She shared how it did nothing to make her feel better. In the end, it did not feel like justice.

This sticks in my head as I think about Banko.

For folks who have been impacted by the system, it’s hard to trust this form of justice. It’s hard to apply these binaries of “good’ and “bad” to an individual knowing that these same labels were applied to yourself and that it is WAY more complicated than “good and bad” when you are navigating survival, which is a spectrum many of us fluctuate on day to day, moment to moment.

Justice for many folks doesn’t look like locking this man up.

For a lot of us, getting the tape released wasn’t about proving this man needed to be prosecuted. It was about clearing Banko’s name, after he was being painted as a knife-wielding, violent, thief..

Justice for me would be Banko being here. Alive. Housed. Safe.

That’s not possible. Banko is not coming back.

So what does justice look like now?

It looks like making sure that what happened to Banko doesn’t happen to anyone else. While that means not having armed security guards in pharmacy stores that serve predominately poor communities, it starts far beyond that.

My wise cousin, Tinisch Hollins, a survivor of violence, and executive director of Californians for Safety and Justice, often reminds people that “When you meet people’s immediate needs, they’re less likely to be harmed again and less likely to commit harm.”

And that is the justice I am looking for.

That’s the justice I want.

We may not be able to bring Banko back, but we sure as hell can prevent more Black trans youth from dying—and Banko already gave us the answer to what we need to fix:

- Black and trans youth need safe, affordable housing that doesn’t take 18 months to access.

- A more coordinated ONE system, the system that homeless individuals in SF have to access in order to get services, with a deep investment in long terms solutions and services, NOT just band-aid approaches. These include shelter for trans folks exclusively or a voucher to access a decent hotel room (NOT IN THE Ls) until a bed opens up.

- It means prioritizing and flagging youth who are exiting the foster care system who have not reunited with family to be prioritized for subsidized or transitional housing so they don’t fall through the cracks. The likelihood of them getting the type of support they need after leaving foster care is slight to none.

- It means guaranteed income. Many people right now are shitting on the Trans District, a program that was established via a city ordinance by the San Francisco Board of Supervisors in 2017. The district, an entity of the City, attempted to create a guaranteed income program that is threatened with court action by Californians for Equal Rights Foundation and American Civil Rights Project saying it violate Proposition 209 and Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. If Banko would have qualified for this program, I have no doubt it would have changed his life.

- It means Black reparations for Black San Franciscans. If Banko and his family had reparations, in whatever form SF chose to distribute them, they’d have resources that could be turned into long-term income or housing for Banko and FOR ALL BLACK SAN FRANCISCANS. The power of seeing yourself as you walk your community and seeing yourself in the businesses you patronize is safety. To be able to offer your people resources it needs because you have the means is power.

- Lastly, it’s mental health services, wellness services, affinity group-specific healing spaces, and access to resources on demand with no strings attached.

While many people were digging deep into Banko’s background, I delved into Michael Earl-Wayne Anthony’s background. I know he graduated from Oakland Tech, he has a beautiful sister he is extremely close to and had a brother who is no longer here due to gun violence in East Oakland. He’s been homeless and had multiple run-ins with law enforcement and his life mirrors a lot of what Banko and his parents experienced.

The difference is, Banko had the Young Women’s Freedom Center. Banko had mentors.

When we talk about ending cycles, they must be cut off as close to the beginning of life to prevent them from permeating the body and turning into trauma and PTSD and anxiety and rage, and resentment.

If we are really about justice, we don’t just want to prevent any more Banko’s from dying, we want to also prevent any more Michael Anthonys too.

I ask you all to keep my siblings at the Young Women’s Freedom Center in your prayers and in your heart. We haven’t even buried Banko… folks are holding so much and are still out here in these streets demanding justice.

Please keep Banko’s friends and family in your prayers. When you have had a light as bright as Banko’s in your life, it can be hard to deal with the darkness their absence cast.

Justice for Banko Brown.

Krea Gomez is a long-time community organizer and native San Franciscan.