Don Ed Hardy, who became obsessed by tattoos when he was only 10 years old, hates how the artform was perceived for a long time in the United States.

“I resented the fact they were so looked down on, and it was an aberrant, antisocial thing like, ‘Oh, were you drunk?'” Hardy said. “It was so demonized. I just thought, ‘Well, that’s wrong.’ If people want a tattoo, they should be able to get one.”

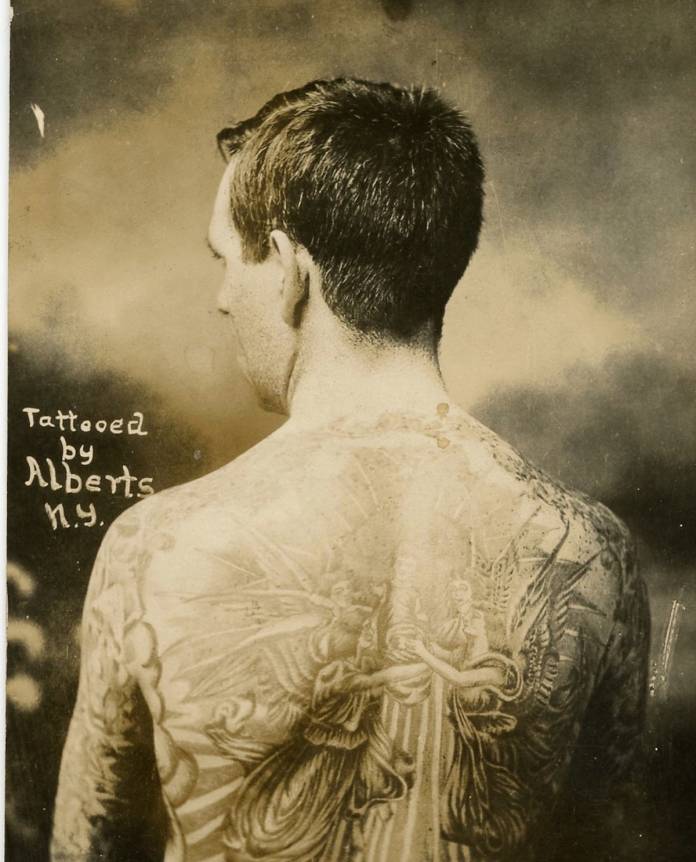

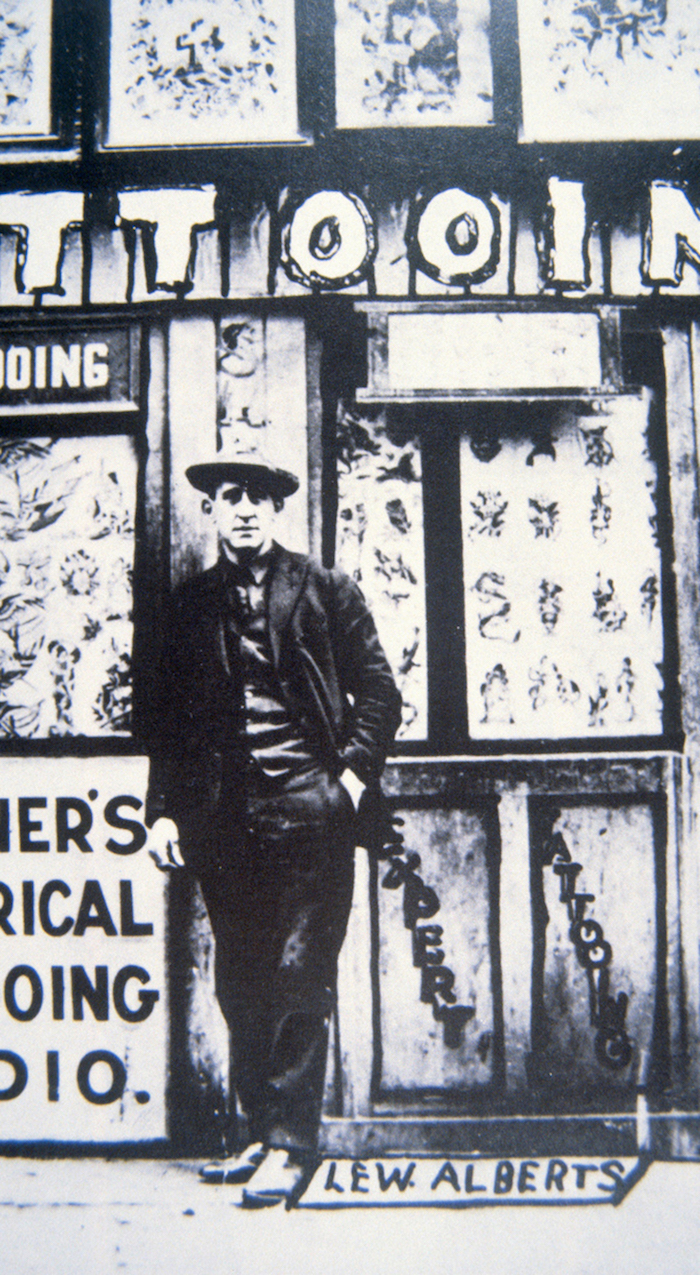

A legendary tattoo artist who splits his time between San Francisco and Honolulu, Hardy started Hardy Marks Publications in 1982 with his wife Francesca Passalacqua. They have published more than 35 books about the history and art of tattoos. His 2015 book, Lew the Jew” Alberts: Early 20th Century Tattoo Drawings, inspired the exhibit, Lew the Jew and His Circle: Origins of American Tattoo, now at the Contemporary Jewish Museum (Through June 9, 2019). About 90 percent of the material in the show—about pioneering tattoo artist and illustrator, born Albert Morton Kurzman (1880–1954)—is from Hardy’s collection, said Renny Pritikin, the curator.

That includes correspondence between Alberts and other tattoo artists, flash sheets that show tattoo designs, and samples of work by Albert’s contemporaries, such as his partner, Charlie Wagner. There’s also newsreel footage of Millie Hull, one of the only women tattoo artists at that time, working on a tattoo.

Back in the ’70s, friends of Hardy’s in San Jose called to tell him they had a couple trunks of antique tattoo material. A tattoo artist had died with no will, so his material went to the state, and they made a blind bid.

“They said you have to come down and see this, it’s incredible,” Hardy said. “It was this whole tattooer’s life—design sheets and machines and all this historic tattoo stuff. “We didn’t know it was Lew. The drawings were all on the backs of received letters and fliers and found papers. I assumed they had been drawn by some tattooer who had been in prison and didn’t have access.”

Hardy and his friends pieced things together by seeing who the letters were from, like, “Brooklyn Joe” Lieber, who worked in Alameda, and C.J. “Pop” Eddy. Alberts’ legacy should be better known, Hardy said.

“He was really a terrific draftsman, and he invented some of these designs,” Hardy said. “He was enterprising in that he was one of the first people to produce commercially printed flash sheets to sell to other tattoers, so he established kind of an image bank that became central to what American tattooing looked like.”

Hardy thinks tattooing was his destiny. He studied printmaking at the San Francisco Art Institute, and he had a scholarship to go to Yale University for graduate school. Then he met Sam Stewart, whose “needle name” was Phil Sparrow, and had moved out from Chicago to Oakland. Hardy calls Stewart, a part of Alice Toklas’ circle, a renegade who changed his mind about going to grad school.

“He was educated and articulate, and he showed me a book of Japanese tattooing,” Hardy said. “When I saw that, I thought, ‘Oh, my God, if tattoos can look like that, I think I want to do this.'”

Hardy who describes himself as a “book nut,” started publishing books about tattooing because he wanted documentation. After his book about Alberts, he ended up meeting his great niece, an attorney in New York, who came to San Francisco for the opening of the CJM show.

“It was a neat connection,” he said. “She remembered meeting him when she was like five or six—he was way retired then. It’s great she came out from New York with a bunch of her family. That really feels good to give some honor to this guy.”

LEW THE JEW AND HIS CIRCLE

Through June 9, 2019

Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco

Tickets and more info here