“Bright, sneering, trashy color, that’s Joan, inexcusably exact, a source of upending forcefulness.”—from poet Eileen Myles’ essay on “City Landscape” (1955) in the Joan Mitchell catalogue.

To put together the Joan Mitchell retrospective at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (through January 17), curators Katy Siegal from the Baltimore Museum of Art and SFMOMA’s Sarah Roberts spent three years, worked with seven researchers, and viewed hundreds of paintings across the United States and Europe. Mitchell (1925-1922), known for her bold, monumental, abstract paintings and her use of color and light, had a complicated career of more than four decades, and in this show of 80 paintings or so—along with photographs, letters, the artist’s sketchbooks, and a display of her paintbrushes—the show aims to present the complexity of her work.

It would be hard to exaggerate Mitchell’s effect on the art world, and during the years the curators spent immersed in her work, they became even more convinced of the artist’s greatness. “She was not just a name we’re going to stick in the canon,” Siegal said. “She was the best, the best—almost without peer.”

As many superlatives as Siegal and Roberts throw around about Mitchell’s brilliance and singularity, the show justifies them all. The paintings, vivid and subtle, many of them massive, practically glow with startling colors that, as Roberts said, should not work together, but somehow do. In “Bracket” (1989), for example, Mitchell combined orange, yellow, brown, gold, green, and blue, making a beautiful painting that seems like it should have been ugly.

Mitchell lived and worked in New York in the ’50s before moving to Paris and then to Vétheuil, a village near the city. Many exhibitions of Mitchell’s art concentrate on either the paintings she made in the US or in France, but Roberts and Siegal say they wanted to show the whole scope of her work.

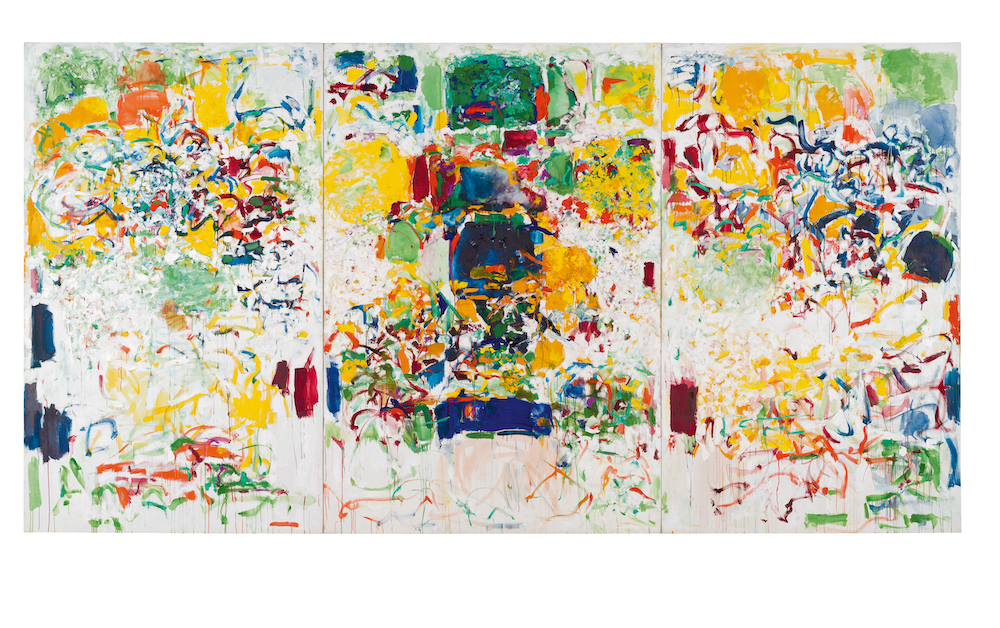

The SFMOMA exhibition (which will also go to the Baltimore Museum of Art and then to the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris) doesn’t have only Mitchell’s greatest hits, but a whole range of work, including masterpieces not seen for decades like “Sans Neige” (1969), a triptych flooded with yellow that has been in storage for four decades (Roberts calls it “one of the most gorgeous paintings I’ve ever seen in my life”), and a painting of reds and blues, “To the Harbormaster”(1957), which references a poem by Mitchell’s friend Frank O’Hara, that hasn’t been on view since the 80s.

The curators said they struggled with how much information they wanted to give about Mitchell’s life, noting that often with women artists, details of their biography get emphasized over their work. But with Mitchell what she was reading, where she was living or traveling, who she was with, and what she was listening to affected the art that was at the center of her life.

“It’s so often been the case for women artists that biography gets sensationalized and is not considered serious scholarship,” Rogers said. “But in her case the work is driven by the biography.”

Mitchell had quite a life. Raised in a wealthy Chicago family, she regularly went to the Art Institute of Chicago and said her favorite painter was Van Gogh, whose influence you can see in her work. Mitchell’s mother was a poet who edited Poetry magazine, and Mitchell wrote poetry as well, publishing it when she was still in grade school. At 11 years old, she declared herself a painter after her father sat her down and told her she needed to choose between poetry and painting.

Mitchell was also a talented athlete—a champion figure skater, a diver, a swimmer, and a competitive tennis player, and in her work, you can see the self confidence that may have come from her athleticism as well as how physical painting was for her. Roberts notes how much Mitchell loved oil paint and used it in all sorts of ways.

“You will see there’s everything from a standard brush stroke to paint thrown through the air and pulled into tight strings and flung and dabbed and globbed and squished and washed and rubbed in,” Roberts said. “The experience of seeing that in person is really just irreplaceable.”

Mitchell also complicated and expanded what it meant to be an abstract painter, Roberts and Siegal said, using it to pull the world close to her, not to push it away. They argue that she was at heart a landscape painter, influenced by her childhood staring out of her apartment at Lake Michigan, as well as her early love of painters like Monet and Cezanne.

A curator once joked to me that California painter Richard Diebenkorn (whose Berkeley paintings are suffused with browns and greens while his Ocean Park series, made in Los Angeles, are full of light and pastel blues) was so influenced by his environment that just walking around the block impacted his work. Mitchell also seems to fold the color and feelings of the landscape that surrounds her into her art. “My Landscape II” (1967), which she made right around the time she bought her property in Vétheuil, has lush greens and blues and seems to reference her views of fields, plants, and water in the country.

In a short video on SFMOMA’s website of painter Stanley Whitney talking about Mitchell’s work, he says abstract painters need to stay close to drama since they’re not telling a story. Along with beauty, Mitchell, who mixed paint right on the canvas sometimes, created drama in her work.

“I like Joan Mitchell because she was just fearless,” he says. “Someone who was really strong willed, very bright, and the paintings show it.”

JOAN MITCHELL runs at SFMOMA through January 17. More info here