MUSIC REVIEW More than four decades into rap’s existence, the genre still struggles with how to present itself live. The bulk of rap shows I’ve seen are more like a DJ set with the rapper hosting, shouting ad-libs and entreaties as their own music blasts from the best speakers you’ll ever hear those songs on. An MC with enough energy can mitigate this problem. Young Thug and Big Boi are two of the best live rappers I’ve seen, if only because they’re so animated as they go through the motions. But when you’re going stop to stop, playing for crowds in towns you don’t care much about, it’s hard to keep up a smile.

Another approach is to bring live instruments into the equation. Live music is almost always more interesting when it’s generated on the spot, because it gives you more to look at and adds a degree of spontaneity that almost guarantees you’re getting something different from what you hear on record. It also guarantees you’re getting your money’s worth, that people are actually working to put on a show for you rather than simply showing up, collecting their cash, and getting back in the van.

Seeing Oxnard rapper Anderson .Paak and his full backing band the Free Nationals live at their 6/27 sold-out show at Bill Graham Civic Auditorium last Thursday, I noticed something curious through the dazzle of the set. There were two drum kits, one manned by the Free Nationals’ Callum Connor and the other by .Paak himself. For long stretches of the show, neither was audible. And when the two drummers synced up, it wasn’t exactly Tony Allen and Ginger Baker going kit-to-kit on Fela Kuti’s Live! Pre-recorded drum beats often did the bulk of the percussive load-bearing, and I had to tilt my head to hear the crash of Connor’s cymbals.

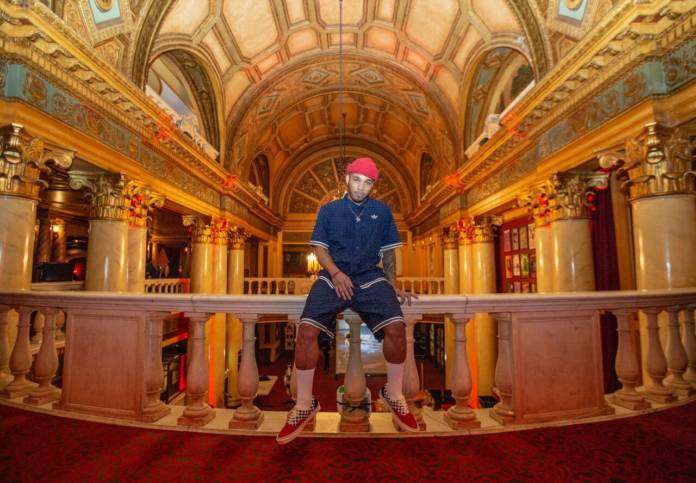

.Paak banks on his artistry. He sings and raps, and as in so much modern hip-hop, the lines between the two aren’t always clear-cut. He’s gifted with a honeyed-gravel voice not a million miles removed from fellow Dr. Dre protégé Kendrick Lamar’s. Put him behind a kit and you have a perfect image of talent and professionalism, especially in tandem with his hat and sunglasses, which make him look like a hip piano teacher, the kind of guy you expect to use words like “cat.” He’s the perfect candidate for a Tiny Desk concert, where you can see him trade grins as well as licks with his dutiful backing band.

I’m genuinely proud of @AndersonPaak for selling out his SF show. It’s lit pic.twitter.com/bYQFBxDgQv

— living deliciously (@galacticstrippr) June 28, 2019

Yet the superfluous second kit suggested that most of the artistry we saw on set was for show, that the backing band was more to have something to look at than to improve the music, that .Paak was drumming more to get a whoop out of the crowd (I saw Margo Price do something similar at last year’s Outside Lands, to much more skepticism than I saw here) than because he wanted the extra percussive heft that two drummers can provide a band.

Perhaps you need a little sleight of hand to be a showman. That word is, after all, most associated with P.T. Barnum, who was wont to do things like graft the top half of a monkey’s skeleton to the bottom half of a fish and pass it off as a new animal. But .Paak is very eager to show. During “King James” the lyrics flashed across the massive screen behind him, ensuring the crowd went apeshit when he sang “if they build the wall let’s jump the fence.” He was often less audible than his two backing singers, who were the most musically essential Nationals—and, with their turquoise suits and quicksilver choreography, the most interesting to look at.

The Bill Graham is a big venue, and big venues call for big spectacles; if you’re shelling out a ticket for a show there, you want a show. But artistry as a prop is no match for real, cold-eyed, uncompromising, take-it-or-leave it virtuosity—and that came in the form of opener Earl Sweatshirt.

The Odd Future alum is, at 25, already an elder statesman. He made his most beloved music in his teens, but he’s spent most of his ensuing career escaping the shadow of that technically astonishing but often morally reprehensible music. His most recent album, Some Rap Songs, is a swampy soup of funk bass and diseased samples that more closely resembles Sly Stone’s most pessimistic music than most of what you’d think of as rap. It’s also interesting because the drums are mixed almost into oblivion, making it impossible to really dance to.

Earl’s torrent of language was the defining fact of his performance, and when he wasn’t spitting, he swayed like a rag doll, teetering as if about to fall over, as if the act of rapping was the only thing keeping him alive. His only prop was a video loop showing images of black men, one seemingly suckling at a woman’s breast. “I’m going to rap at you for 25 minutes, then I’m gonna get out of here,” he said as he shuffled onstage. Take it or leave it. Most people took it, and the Graham was a sea of nodding heads and plumes of blunt smoke.

“He’ll play his early music if he’s in a good mood, his new music if he’s in a bad mood,” I heard one concertgoer say to his friend. Earl must’ve been pretty grumpy. Music from 2010’s EARL was off the table, and his lyrics were cryptic when they weren’t disarmingly personal. Like .Paak, Sweatshirt presented himself as a professional, but his definition of the term is more dogmatic than technical. His almost misanthropic intent was exhilarating, and all the pyrotechnics that shot out of the stage during .Paak’s set seemed pale next to the fire that burned in Earl Sweatshirt’s eyes.