More than 40 percent of union workers in San Francisco have been forced to leave town because of high housing prices, a new report by the Council on Community Housing Organizations, San Francisco Labor Council, and Jobs with Justice concludes.

The report, which represents an historic collaboration between labor and affordable housing advocates, gathered income and residence data from roughly 50,000 union workers, creating a map of geographic dispersal of workers across various income levels.

The report concludes that the city needs more non-market housing to create new units that will affordable to its workforce.

Workers surveyed include custodians and janitors, hotel and stadium workers, security guards and airport workers, educators, transit workers, electricians, health workers, firefighters, and nonprofit and public sector workers.

Of all workers surveyed, only registered nurses were considered not to be “rent burdened,” as defined by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development, under San Francisco market-rate rent, meaning having to pay more than 30 percent of their pre-tax income on rent. Registered nurses in San Francisco on average earn $162,469 annually.

Only 4.6 percent of households could afford the monthly payments for a median-priced home in San Francisco, according to the report.

The median annual income for workers surveyed in the report was $67,350, equal to 73 percent of San Francisco’s Area Median Income, placing half of surveyed workers well below the city’s benchmark for “low-income,” which is 80 percent of the city’s AMI.

San Francisco’s overall AMI is $93,250, and the average rent for a one- bedroom San Francisco apartment is $3,289 according to Zumper data used in the report.

District 7 Supervisor Myrna Melgar said that the lack of affordable housing forces lower-income workers to commute into San Francisco from the Bay Area’s outer fringes, and said this has negatively impacted local communities and the environment.

“When people can no longer afford to live where they work, we lose them and their families as active members of our San Francisco community–and our schools, churches, unions,” Melgar said. “Failing to house our workers also worsens our carbon footprint, forcing people to commute to their jobs from ever greater distances.”

The report also found that the city would need roughly 2,000 affordable housing units annually, triple its current production of affordable housing to meet the needs for housing workers.

According to a 2019 Budget and Legislative Analyst 2019 report, San Francisco will need an additional 11,869 affordable housing units by 2026 to accommodate growth in lower-wage jobs, but the city already has enough market-rate housing already built or planned to be built to accommodate the workers who would fill growth in higher-income jobs.

Supervisor Gordon Mar said that focusing housing development on creating market-rate housing will not address the lack of housing for low and middle-income families in San Francisco, and that the city must enact local policies that foster the creation of affordable housing.

“I think we can all agree that the housing and development policies the city has followed in the last decade has failed to address the housing affordability crisis…that’s going to mean focusing on meeting the actual unmet housing needs for our workforce and not just relying on more and more luxury condos and apartments and hoping this will have a trickle-down effect,” Mar said.

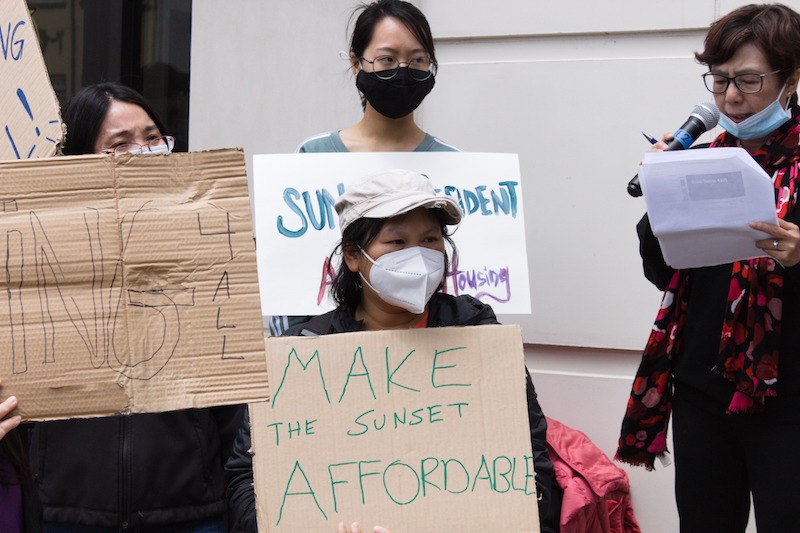

Some local policies Mar has backed include converting single-family homes to duplexes and quadplexes with incentives to keep rents affordable for middle-income families and a pilot program to allow homeowners in the Sunset to add accessory dwelling units to their homes. There are also two 100-percent-affordable housing projects in Mar’s district, one at the site of a former Police Credit Union Branch at 2550 Anza Street and another targeted towards housing local educators at the site of the Francis Scott Key Elementary School in the Outer Sunset.

“I am looking at other opportunities to create 100 percent affordable housing, but I am also looking at new models for financing and developing affordable housing for moderate-income households, whose needs have not been addressed through our housing development strategies until now,” Mar said.

Some of the report’s recommendations included fostering 100 percent affordable housing development through use of housing co-ops such as the ILWU-sponsored St. Francis Square, down-payment assistance programs for prospective homeowners, and preventing the privatization of public land, turning it over for affordable housing development instead.

“There is certainly a place for market-rate housing in San Francisco, creating jobs and supporting the economy, but…what San Francisco working people face is a crisis of affordability,” the report read. “To truly provide housing stability and long-term security for workers such as those featured in this report, in proximity to their workplaces, depends on solutions that de-emphasize land and housing as commodities, that support housing production that is needs-based rather than simply market-based, and that reduce incentives for speculation—with a goal to achieve a true jobs-housing fit.”