LISBON – With COVID restrictions waning, it seems as if half the reporters and politicans in San Francisco are going to Europe this summer, and (of course) Heather Knight is among them. She (of course) complains that the streets are cleaner in European cities, and that there are far fewer homeless people.

She mentions only once that there might be a reason for that:

Of course, European countries tend to provide much more robust health care and have a safety net that catches people before they’re so far gone that they’re walking into busy streets in hospital gowns.

I am in Lisbon for an old friend’s daughter’s wedding, and I agree: There are fewer homeless people, although not zero. There is also national health insurance—ranked among the top in European countries—and housing is way less expensive than it is in San Francisco.

The national health service covers mental health, and psychiatric hospitals [in Portuguese] can also ensure mental health care services at the local and regional levels. Moreover, it offers long-term and specialist inpatient care to patients with serious mental health issues that have no family or social support.

Since the development of the National Mental Health Program, there has been a 40% decrease in the institutionalization rate. This health policy aims to improve patients’ life conditions, develop rehabilitation programs, promote home care, and support their reintegration into the community.

In Knight’s story Sup. Rafael Mandelman talks about how this city has “a lower tolerance for this level of disorder.” Maybe, but as far as I can tell, Portugal gives mental patients extensive rights and involuntary confinement is difficult.

All of this does not make Portugal a perfect paradise (although the beaches in Siembre are pretty fantastic, and a pint of Super Bock and a superlative ham-and-cheese sandwich costs $7). The place has a long history of political corruption, which continues to this day. I would not like to tangle with the Portugese criminal-justice system.

So let me make another comparison, which is typical not just of Portugal but of many European countries. You can read my friend Steve Hill’s book about it.

Europe practices what Hill calls “social capitalism,” where the market is tempered by higher taxes on the rich, a robust social sector—and a general, if imperfect, recognition that the entire purpose of society is not to create vast wealth for a few but to make the lives of all workers better. (Most European workers are guaranteed by law or union contact between four and six weeks paid vacation a year and at least six months paid parental leave.)

Let me give just one key example.

Under the Portugese tax code, a person who earns $150,000 a year takes home $76,000. (The Euro and the dollar are pretty much at parity today, so I am using dollars for comparison.) That same person in the US takes home $112,000.

If you make $1 million a year in Portugal, your after-tax income is $434,000. In the US, it’s $640,000.

The corporate tax rate is 21 percent—and it applies to income that a Portugese corporation earns anywhere in the world. So here, Apple couldn’t hide its income in Ireland and avoid taxes.

In Portugal, when you sell real estate, the profit is treated (and taxed) as ordinary income, not capital gains, and the rate is 28 percent. In the US, it’s 20 percent.

Most of the land and industry in Portugal was once owned by seven families, and despite the role of the Communists in the revolution that toppled a long-running dictatorship in 1974, their descendants are still wealthy. There is poverty here, especially among immigrants from outside the EU. The Gini coefficient for economic inequality ranks Portugal as the worst in Europe—but as with every European country, it is still far, far better than the United States.

Yes, in some areas the government is corrupt, and not all the money goes where it should, and I’m sure a lot is skimmed by people who don’t need or deserve it.

But in a sense, that’s not the point. French economist Thomas Piketty, who by any reasonable account is the most important thinker in that field since Marx and Keynes, argues that taxing the rich at a high rate is by nature good for society, even if you just take the money and throw it in the Ocean. That’s because high taxation reduces economic inequality, which Piketty argues is the most important threat to human society other than global climate change—and they are, of course, directly related.

If you take half the income of the very rich, they have less to spend on, say, housing, which means housing isn’t as expensive. When the US took 80 percent of the income of the rich in the post-War era, housing and many other goods that are priced based on competition were far cheaper.

Heather Knight hasn’t talked much about that.

****

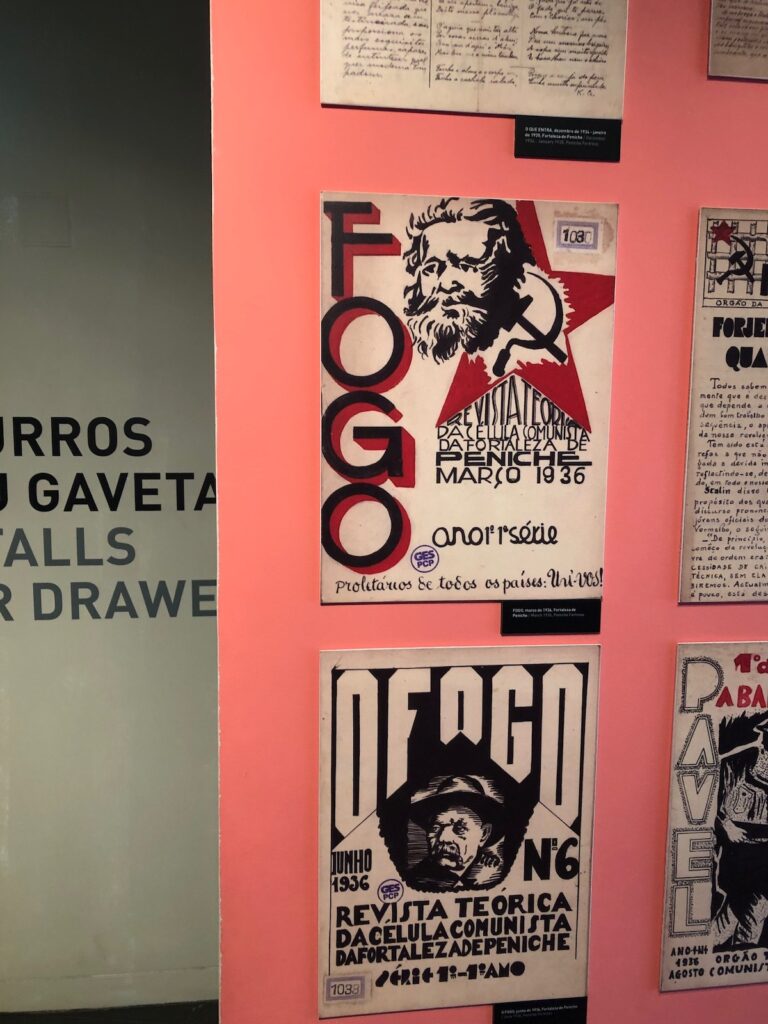

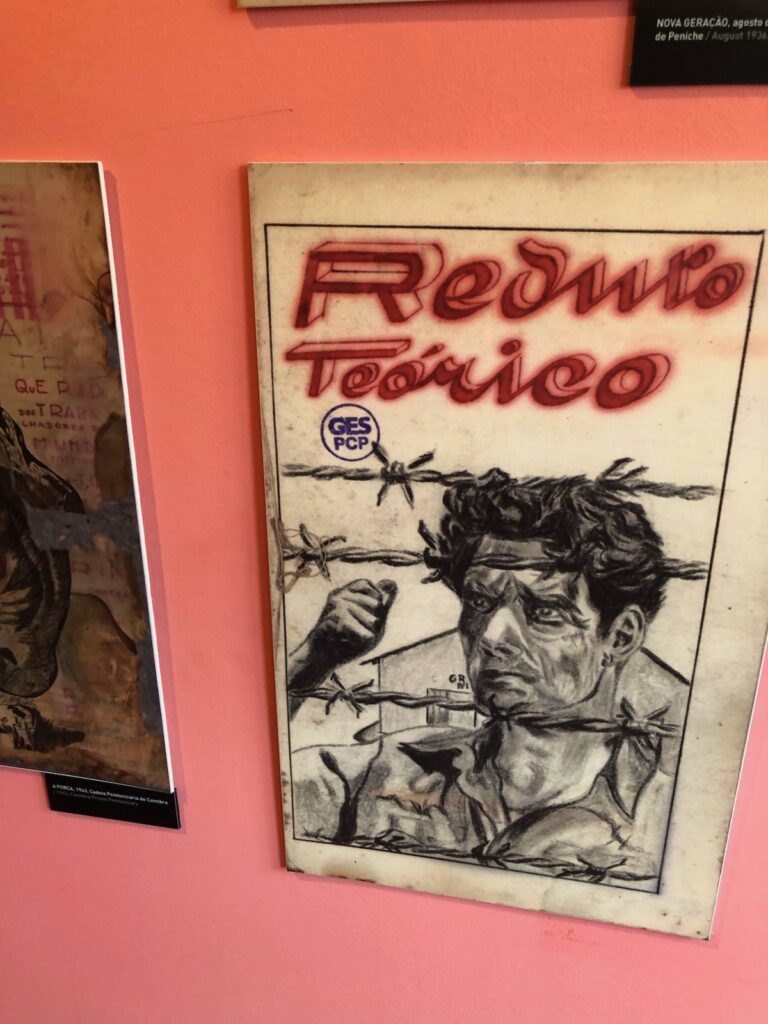

There’s a museum in Lisbon that’s dedicated to the history of fascism and resistance, which this country has experienced in a serious way. I have learned a lot about Portugese history in the past week. (Yeah, I’m a nerd that way—I didn’t know, for example, that during World War II the British and the Nazis fought a secret, often bloody underground battle over access to Portugal’s tungsten, which both sides wanted for armaments. Portugal was officially neutral, but both sides had spies and operatives who bribed everyone in sight for access to a mineral that was at one point more valuable than gold.)

From 1926 to 1974, Portugal was under the thumb of a brutal dictatorship, run for most of that time by Antonio Salazar, who had a stroke in 1968. Salazar was a corporatist; under his regime, land, industry, and finance were consolidated to the point that the seven families basically controlled all of the country.

The museum is in one of the old prisons where critics of the regime were tortured and killed.

I saw all sorts of Communist posters: The Communists were leaders in what would become the Carnation Revolution in April, 1974. They were not the only ones; the revolution was led by young military officers from the academy who were left-leaning but also pissed that Salazar was promoting untrained officers for political purposes.

But after the revolution, the new government gave up all the colonies, and created, in fits and starts, a semi-stable multi-party democracy. (The socialism gave way in the 1980s to Cold War anti-Communism.)

My son and I watched some of the old video footage of Salazar’s speeches. He talked about “truths” that “could not be challenged,” including loyalty to family (in which women didn’t work and were the subject of their husbands) and the nation that he led.

“You know,” my son said, “He sounds just like Trump.”

Perhaps there is a lesson here.