Recent unionization drives have been all over the news, from Starbucks to Amazon—but how can the history of organizing, especially in extremely consequential places like California, be taught in a way that students will find relevant to their lives and work?

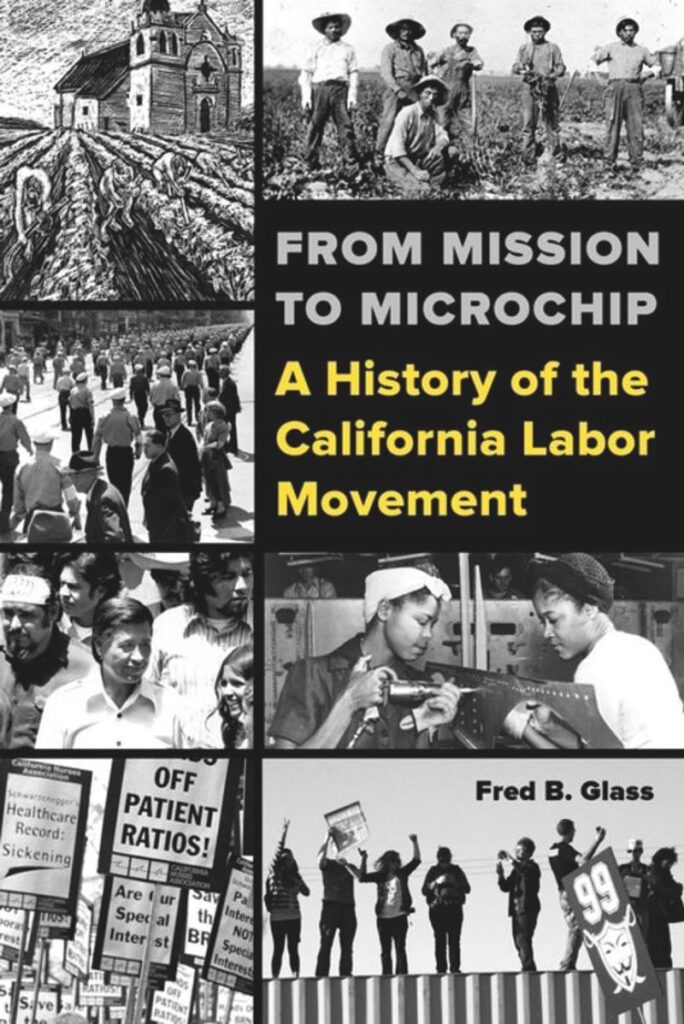

Ask Fred B. Glass, former Communications Director for the California Federation of Teachers and currently an Instructor of Labor and Community Studies at City College of San Francisco. He is the author of From Mission to Microchip: A History of the California Labor Movement and the producer of Golden Lands, Working Hands, a 10-part documentary video series on California labor history, and has a real grasp on how labor organizing history stretching back more than a hundred years applies to the here and now.

This semester, Glass will teach California Labor History at the Mission Campus of City College of San Francisco, as part of the Labor and Community Studies Department. This course is tuition-free for residents of San Francisco thanks in large part to labor and community organizing. Visit ccsf.edu/register for more information

48 HILLS Your book From Mission to Microchip tells the story of California’s working-class movements. What does this story add to our understanding of work and labor?

FRED GLASS Most Americans grow up with a weak understanding, at best, of history. Part of the problem is the superficiality of commercial culture, which treats history mostly as background for love stories or war sagas, or pop genres like science fiction TV shows that send their characters back in time. Another difficulty is that history is mostly written or commissioned by the victors, meaning the ruling class, who are not so interested in sharing the lessons of working class victories.

In our capitalist society, history is most often taught about “great men” doing “great deeds” at “great moments”: like your basic PBS documentary voiceover intoning, “On December 7, 1941, Franklin D. Roosevelt declared that it would be a day that lived in infamy.” Not only does this mean that working people, who must provide the bulk of the work that allows history to move forward, are mostly left out of the picture. It also means that most students have nothing to relate to in history told this way that matches up with their own experiences.

As a result, most people feel that history is boring and irrelevant, which is too bad, because labor history is all about “most people”—the working class majority—and provides fascinating glimpses into those moments left out of official historical accounts, the moments when workers make history.

The simple difference between “great man” history and labor history is that unlike presidents, generals and capitalists, who as individuals can flip a switch and change the direction of events, for workers it takes collective action to make history. This is harder, and doesn’t happen every day. But it does happen, and finding out about that can be empowering, and interesting, and a counterweight to the feelings of irrelevance and inevitability and “why bother?” that the other kind of history makes most people feel.

48H What inspired you to write this book?

FG Two things. First, my family. I grew up in a union household in Los Angeles. My father and his brother were both musicians, and belonged to the American Federation of Musicians at a time when that union had much more of a presence and much more power than it does today. Their union helped these two sons of immigrants become homeowners, support families, and send their kids to college.

It was a time when a third of the country’s working class belonged to unions, and there was an oral culture of unionism in families, friends, neighborhoods—anywhere people gathered—that let new generations coming up know what advances unions had made for the lives of working people. I learned about these things in my house, and in the homes of my uncles and aunts, several of whom were active in garment worker and steel worker unions.

With just 10 percent of the working class enrolled in unions, that oral culture is mostly gone today; the book, like my video series, is meant to address that hole in our state’s history where unions should be.

The other inspiration was when I was communications director for the California Federation of Teachers I got asked by leadership to write a regular labor history column for one of our publications. I got hooked on researching California labor history, and began teaching it at CCSF more than thirty years ago. I discovered that the last time anyone had written an overview history of California labor history was in the 1970s, and that little book, just one hundred pages, was pretty much useless for my students. I got tired of patching together dozens of articles for the class. So I wrote the book myself.

48H Is there a particular story you tell in your book that is instructive for young organizers, say at Starbucks or Amazon?

FG: There are so many of those. I’ll just mention one. In 1903 Japanese and Mexican farmworkers were brought in by labor contractors from their countries to work the beet fields outside of Oxnard. It was hard, dirty, often dangerous work, and the corporate beet growers consciously used racial, language, and cultural differences between the two groups of workers to keep them divided and thus unable to effectively organize against the miserable conditions of their work and lives.

And yet that’s what they managed to do, forming the first union in California’s fields, and defeating a wage cut. The number one organizing tool that the bosses have at their disposal during a union organizing drive is sowing fear and division among their workers. The Oxnard story suggests that if under these conditions 120 years ago workers could overcome divisions and organize, it can certainly be done today in a coffee chain, a logistics empire or a tech company.

48H California has a reputation for progressivism. According to the Public Policy Institute, the gap between high- and low-income families in California is among the largest in the nation—exceeding all but four other states in 2020. How should this disconnect between rhetoric and reality be addressed?

FG Much of what we think of as progressive California values comes from or is protected by organized labor.

California, like New York, has always been a gateway for immigration. California has a higher percentage of immigrants than any other state. First generation immigrant workers usually have to work their way up out of poverty. While the labor movement’s historic record on immigrant rights is mixed (and for a long time was terrible), today it is a strong supporter of immigrant worker rights. This means that if you strengthen labor laws you simultaneously raise up immigrants and all workers.

That’s one side of the equation. Another is to understand the level of wealth accumulated in this state. We have a quarter of the country’s billionaires in California. If the state were a country it would famously be the fifth biggest economy in the world. This represents an unprecedented amount of wealth, stoking economic inequality, and unbalancing our democracy.

So here we have higher highs and lower lows than in the rest of the country. That can be addressed by stronger unions in the workplace and more progressive tax laws (which are typically spearheaded by unions) to properly redistribute the wealth.

48H This semester, you are teaching California Labor History at City College of San Francisco. What can students expect to learn in your class?

FG: My students can expect to learn about the hidden history of working people’s struggles for power and for their rights. They will learn about the colorful personalities, the transformative events, the culture and the organizing strategies devised by workers and unions across a century and a half of struggles for a better world.

They will see how organized labor relates to movements for social justice of all kinds; and they will examine, decade by decade, the successes and failures of the California working class. They will also learn how those events link up with and shed light on today. Often the class helps them unearth these kinds of stories within their own families—stories that they never knew were there, or knew about vaguely but never explored before.

48H In recent years, many colleges have phased out Labor Studies. Why is this? What do you think are the consequences of this in our civic life?

FG: There are 116 community colleges in this state. Every one of them has a business department, teaching students how to run a business. There are a mere half dozen that offer labor studies courses, and only three of those currently offer a degree in labor studies.

This imbalance has to do with the decline of labor’s size, power and influence over the past several decades. This didn’t happen in a mysterious or inevitable fashion. It was the result of a concerted campaign—in the workplace, in politics, in the mass media, in the courts—by wealthy anti-union conservative forces, who have been largely successful in their aim, which is to siphon more and more of the wealth produced by the working class upwards into the bank accounts of the already rich, and roll back what power workers have through their unions.

Labor Studies has been a conscious if secondary target of these forces. Compounding the problem has been the austerity budgets placed around the necks of institutions of public higher education, forcing college administrations into zero sum budgeting games, which disproportionately affects smaller departments.