Liz Hernández draws from her Mexican cultural heritage to document an autobiographical synergy of memory, present day existence, everyday domestic objects, and supernatural symbolism. Merging dual worlds, Hernández shares her story in mixed material paintings, clay sculpture, and the written word.

“I like to incorporate some mysticism into my work, to create stories that might never become real, but are nice to exist in momentarily,” Hernández told 48hills.

Hernández found a way to become an artist by her own method. Although she completed a 2015 BFA in industrial design from the California College of the Arts, she has never worked as an industrial designer.

“It was my sneaky way to go to art school, but I did not get formal training in fine arts,” she said.

Her parents would never have supported her desire to major in art, so studying design was her closest option. Even Hernández once saw art as an impractical luxury. Now, she considers it a necessity. Studying design exposed her to the many materials and techniques that have influenced her art practice.

Hernández grew up in the suburbs of Mexico City. As a child, she loved drawing, writing, photography, and playing music; activities she usually did alone, almost in secret. She realizes now that this was a period of introspection, both therapeutic and invigorating.

“I process my feelings and thoughts by creating an object, an image, or a piece of writing. Once it is out of me, I feel a huge sense of relief. It also allows me to dream up different worlds and explore the unknown,” Hernández said.

She moved to Oakland when she was 19 to attend CCA. She had no plans to stay in the Bay Area, but after graduation she changed her mind.

Hernández does not want to forget who she is and where she comes from. Her work is highly personal, and sometimes it feels scary to share it with an audience. What she has discovered, however, is that many others share the same experiences, and that art can allow a dialogue on issues that might otherwise be unapproachable.

“Whenever someone tells me they connect with something I made, it blows my mind,” Hernández said.

She is most inspired by Mexico’s history and popular culture: its crafts, pre-Hispanic mythologies, anthropology, family stories, matriarchal societies, Catholic rituals and paraphernalia, and Latin American literature.

“Another big inspiration are the quirks of life in Mexico City, because it is a place that promotes curiosity, frustration, and disbelief,” she said. “It is also a city where the past and the present interact in the same space, which I have always been fascinated by. A 16th-century church next to an Aztec temple a few steps from a taqueria is one of the most confusing things I have seen.”

She misses walking down the street and finding something that completely perplexes her, that breaks with everyday normalcy, even if not always in a positive way.

Her practice is deeply tied to this juxtaposition of visuals.

“Finding beauty in hand-painted signs on buildings or stumbling on a shrine for the Virgin Mary built with random trash and Christmas lights inside an underground parking garage—I never needed art galleries, because the streets presented me with astonishing images,” she said.

Hernández is also inspired by photographer Graciela Iturbide’s ability to capture rather than overly romanticizing reality. Iturbide’s life story parallels her own in some ways; lack of family support for creative inclinations; persistence; a fascination in Catholic paraphernalia; and curiosity as an observer.

“Iturbide resonates with me more than any other artist. You can see harmony but sometimes tension [in her work.] She is looking for something to surprise her,” she said.

In West Oakland, Hernández and her husband, Ryan Whelan, recently transformed an abandoned office space into a studio.

After cleaning and painting the walls and floors, they created an inviting space full of light, with a small kitchen and seating area, separate studios and a woodshop. It is filled with jars of vinyl paint in a small range of colors, a huge canvas roll and stretcher bars, lots of paper, sheets of aluminum and brass, boxes full of sculpting tools, and cases of embroidery floss organized by color. Arriving early and often staying late into the night, Hernández takes her time getting into work mode, often writing before stretching a canvas.

“I cannot jump right into making. I read, listen to or watch something related to the work and contemplate it deeply, which eventually leads me into production,” she said.

But though this is where she works, her home is where inspiration begins. A former convent near Lake Merritt with arches and high ceilings, plaster walls, and creaky hardwood floors, the remnants of her domestic space’s past inspire her.

“This environment allows me to be reflective. It was a space designed for that purpose and we feel it,” she said.

Hernández has noticed an evolution in her work over the past two years. In 2016, she began painting with clay and creating works about vessels. Later, as she took to showing work publicly, she turned to traditional materials to create colorful, flat, yet intricate paintings. Later, she began work on a series of still-life paintings depicting the markets of Mexico City.

“The pink canopies cast a rosy glow over vendors’ goods, often cutting into sculptural objects for display. I’m describing the experience of stepping into the market within a bustling city, so far removed that it becomes a self-contained world,” Hernández said.

Opportunities appeared to create public murals for tech companies, but in 2019, she decided to return to using clay to paint on canvas, only now with a solid idea of what she was trying to communicate. She is constantly learning new techniques to grow her vocabulary, utilizing metals, ceramics, embroidery, and papier-mâché. Recently, she collaborated with a friend in Mexico City to create a short film.

As a deep thinker who finds comfort in being alone, Hernández was very productive during the isolation of the pandemic. But she was not immune to seeing others suffer. It reminded her to look beyond herself, and a natural inquiry about death and one’s purpose in life emerged.

She made more effort to reconnect with family, and with the syncretic fusion of spirituality she learned as a child. Though attended Catholic school most of her life, but her maternal family was also part of a religious movement called Espiritualismo Trinitario Mariano, which originated in Mexico City in the 19th century. A mixture of religions, traditional medicine, and spiritism, the faith inspired Hernández to examine it more deeply. In 2020, Pt.2 Gallery in Oakland, the gallery that primarily represents her work, exhibited “Talismán,” a show based on this research.

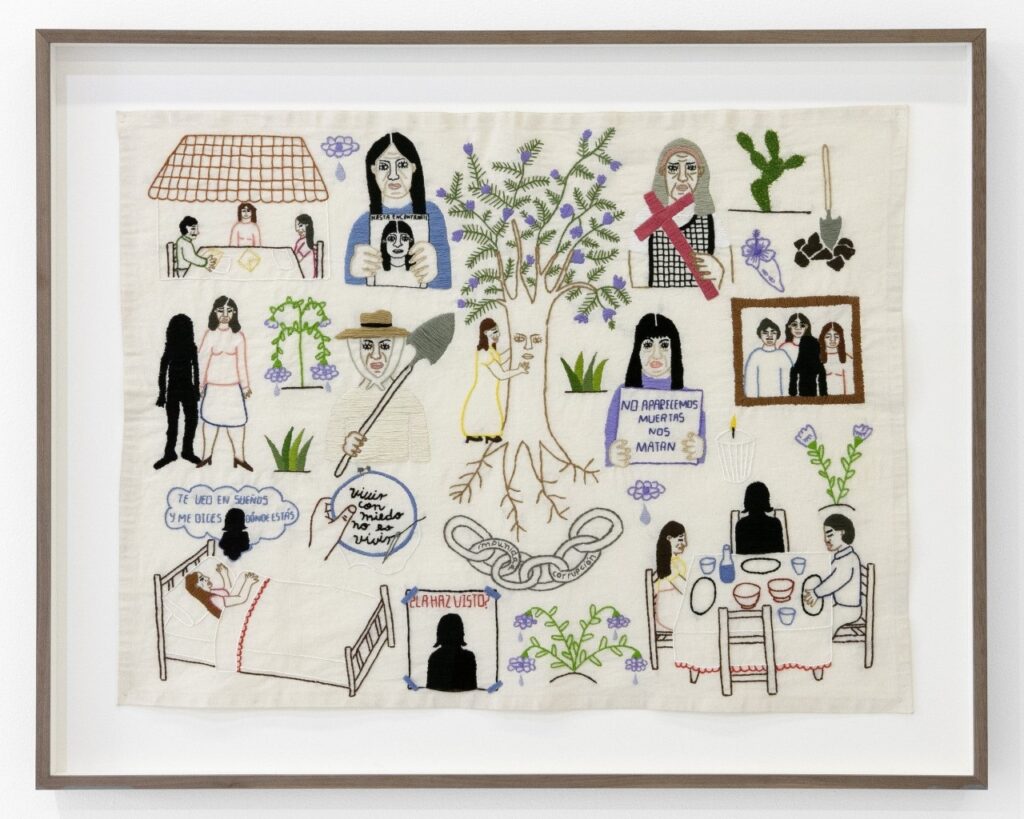

More recent exhibitions include “Shifting the Silence” at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; “Bay Area Walls,” a commissioned mural also at the MOMA; “Tikkun: For the Cosmos, the Community, and Ourselves” at The Contemporary Jewish Museum; a solo presentation at the ZSONAMACO fair in Mexico City; and “Donde las flores moradas lloran (Where the purple flowers cry)” at Pt. 2 Gallery. Hernández also participated in the FOG Design + Art Fair in January 2023 and collaborated with Whelan on mixed-media paintings for the exhibition “A Weed By Any Other Name” at the new Institute of Contemporary Art San Francisco (ICASF), which runs through June 25.

“In this show, we consider the blackberry, humble and wild, as a symbol of resilience and a vehicle to invoke the unease, precarity, and networked resistance of people who live in the Bay Area,” Hernández said of “A Weed By Any Other Name.”

The work was triggered by the couple’s fear of displacement. Realizing this experience is not unique to them, they questioned if it is a local rite of passage.

Liz Hernández will continue to blossom, and is learning the importance of dedicating herself to the things about which she feels most passionate. In 2023, she aims to slow down to let new ideas incubate and develop, to envision what she wants for her life and her art. She urges us to do the same with this simple apopthegm:

“Always stay true to yourself.”

For more information, visit her website at liz-hernandez.com and on Instagram.