When I was writing my 2020 book Into the Streets: A Young Person’s Visual History of Protest in the United States, I figured that once I got to the protests I myself was involved in, as a very loud and proud Gen Xer, things would be easy. Surely nothing could shock me about the terrible things I’d seen perpetrated in the name of American hegemony after covering centuries of colonialism, genocide, oppression, and racism, no?

But I was blown back by the emotions that came up as I dove into the the chapter on the Iraq Invasion—launched on March 20, 2003—one of the most cynical, not to mention evil and illegal, actions in a history fraught with them. Suddenly, I viscerally remembered feeling so helpless in the build up to it all, the suffocating cultural conditions that snuffed out all dissent as “unpatriotic” (ugh), the near-universal cheerleading which saw everyone from Britney Spears to gay liberal Dan Savage supporting the Bush administration’s shady maneuverings. It’s still something to be very, very upset about. Especially as there has been zero accountability or personal consequences for those who orchestrated and preached it.

As a person of Arab descent—and queer at that—I experienced the racist vitriol that poured forth after 9/11, helping those who twisted the country’s justified anger (and moment of unified grace) into a disgusting global tantrum that killed hundreds of thousands of innocent people.

It was tiresome to be pulled aside for the umpteenth time from the airport security line to be patted down; it was heartbreaking to hear my adoptive parents warn me to be careful; it was kind of fun to wear a white hat and stand up suddenly in public places, drawing panicked gasps from the crowd around me. (As someone who was probably the exact opposite of a religious terrorist, I had been “radicalized” into anti-war activism at college in Detroit, near the the country’s largest Arab population, in the midst of the Gulf War’s “these colors don’t run” jingoist fever dream, during which I was actually and somewhat hilariously called a “towel head.”)

None of what I experienced was close to the racism that caused so many random Brown people in the country to be physically attacked and murdered in the 9/11 aftermath. The nation’s brain was rot. It honestly came as no surprise that the “USA! USA!” could so easily drum up support to invade and destroy a country that had no relation to the terror of the Twin Towers, simply because that country was full of poor Brown people, and Americans couldn’t and wouldn’t be bothered tell the difference among any of them. Kill ’em all, and let God sort ’em out, amirite?

In the 20 years since, it’s also been unsurprising that United States media and entertainment industries have memory-holed their complicity in the invasion. Has there been one book, movie, or TV show from the point of view of those we invaded? Or has it all been either Hurt Locker rah-rah-rah or quickly buried, portentous and weird prestige projects? In the 2000s, Hollywood found a way to sublimate the horrors of Abu Ghraib and guilt about the violent occupation through the extremely profitable torture porn genre. In the dozen years since Iraq in general has simply dropped from the media radar, unless it’s part of some fictional US veteran redemption story. And when was the last time, before this 20th anniversary week, that you saw a major news story about Iraq? The mainstream news media has instead invested in wiping itself clean.

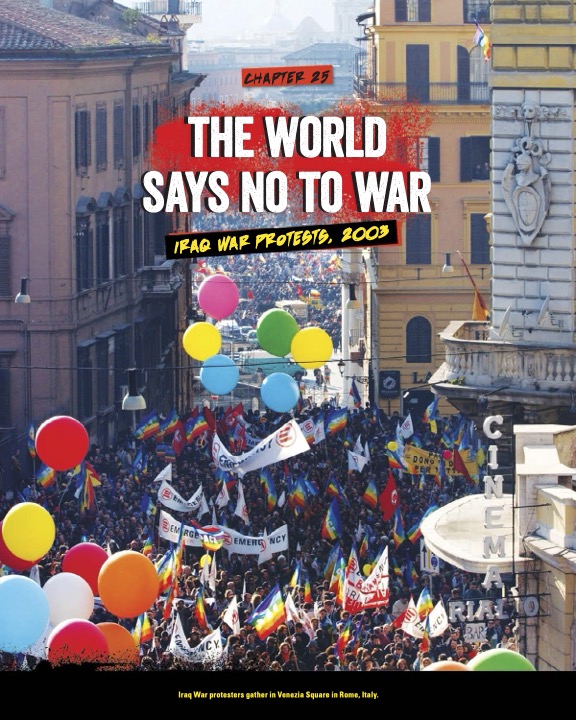

But since I was writing a book about protest, there was something inspiring to lean on. First, although there was plenty of media coverage and a very active internet at the time, it’s taken a couple decades to truly appreciate the scale of resistance that was taking place. Worldwide protests leading up to the “war” were among the biggest and most expansive of their kind ever recorded. At least five percent of the US population, a stunning number at the time, said it had taken part in a protest after the invasion. Tens of millions of residents poured into the streets in cities and towns across the globe as the world said, “no.”

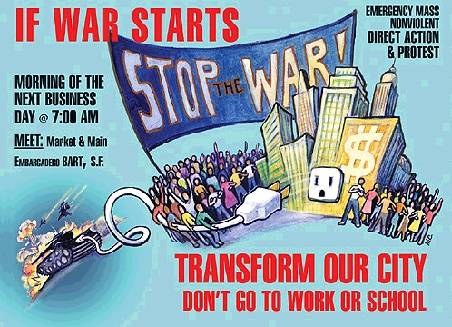

Video of a protest during the lead up to the war via FoundSF

I was in a restaurant bar in the Mission on March 20 when I started to see coverage of the heinous “shock and awe” bombardment of Baghdad broadcast on the TV, and my heart sank so much I had to run to the bathroom. (Sorry, Puerto Alegre.) When I came out, I saw a river of people spontaneously leaving establishments and marching in the streets. I joined them and ended up marching through the city streets all night as various acts of civil disobedience filled corners of the city. (Luckily, I met a cute Cabo Verdean boy who made marching a lot less hard on my feet.)

As FoundSF puts it:

On March 20, 2003, tens of thousands of anti-war protesters took to the streets to advocate against the U.S. invasion of Iraq. This became known as the “battle of San Francisco” because of the intensity and scale of the protests. Protestors filled various intersections across the city, blocking the streets, chanting, drumming, locking themselves to plastic pipes, and confronting policemen. The first day of protests continued until 4am on March 21st, and throughout this time there were 1400 arrests. During subsequent days, the number of arrests rose to 2500. Yet despite the intensity of the protests, the U.S. invasion of Iraq continued.

We shouted protest slogans—many nicked from the lively 1980s protests against Central American occupation, a strong moment of local organizing—until we were hoarse. We shut down the Bay Bridge. We kicked in a few trash cans. And although we felt we were screaming uselessly into the void, of course we weren’t. It was then, and at all the giant Bush puppet-filled protests in the years afterwards, that I was able to preciously connect with others who felt the same way I did.

That lack of isolation created networks for the future, ones that have kept people engaged, committed, and hopeful through the decades. Looking back, we planted the seeds to inspire future meaningful protests like Occupy, the Peoples’ Climate March, the anti-Trump Women’s Marches, and the anti-gun March for our Lives—just as we took our lead from the Vietnam Anti-War Movement, 1999’s WTO protests, anti-nuke marches, and others.

Iraq is horribly damaged and polluted, we are dealing with a terrifyingly expensive legacy of US military veteran PTSD, and the unjust invasion and occupation of an oil-rich country has wreaked lasting havoc on this country’s foreign policy. (It’s one of the major reasons the US lacks non-Western backing in defending the Ukraine, for instance.)

All we really have to show for the disaster, 20 years later, is that some people refused to take it all silently—and loudly spoke out.