One of the biggest hits released in 1973 was Serpico, which plays the 4Star in SF this Wed/24-Thu/25. It was not so huge as such better-remembered films also turning a half-century old this year as The Exorcist, The Sting, or American Graffiti, but unlike them illustrated the era’s penchant for gritty crime dramas that were often more focused on character than action. Like The French Connection, which kickstarted that vogue two years earlier, it was based somewhat loosely on a true story, with many names changed.

But there really was a Frank Serpico, a plainclothes officer who really had blown the whistle on widespread NYPD corruption in the 1960s, and lived (albeit barely—he was shot in a 1971 drug raid that may have been set up to silence him) to tell the tale, in a book written by journalist Peter Maas. All that made him famous, if hardly popular among colleagues; he “retired” and spent the rest of the decade keeping a low profile in Europe. But the reforms his testimony (as well as that of a few other, lesser-sung cops) forced into being had considerable long-term impact on police conduct, in NYC and beyond.

The real Serpico didn’t like the film version of his story, because it departed from facts and because producer Dino De Laurentiis fired original director John G. Avildsen (of Joe and later Rocky), replacing him with Sidney Lumet. But the latter was usually at his best in such urban-crime thematic territory, and his unfussy, docudrama-ish style befit a production that had to be shot fast to accommodate the star’s imminent Godfather II schedule, as well as a planned Christmas release.

Today, Lumet’s non-hyperbolic, procedural tenor and attention to location-shot detail (though oddly the film does nothing to convey the great cultural/fashion changes of its 1960-71 timespan) is both a great strength and a limitation. Serpico never becomes electric, as French Connection does; it is not much interested in chase scenes or violent setpieces. Instead, the emphasis is overwhelmingly on Al Pacino as Frank Serpico, as a slightly peculiar (at least by NYPD standards), straight-up but not particularly stuffy or saintly regular guy.

Graduating from police academy as an Army vet and college graduate, he’s viewed as never quite fitting in with his fellow cops—he’s not a snob, but their loutish locker room-style camaraderie isn’t his thing. Nor is the graft they routinely extract from variably shady characters on their beats something he wants any part of, a refusal that awakens their deep suspicion well before he even thinks about whistleblowing. He attends night school just to better himself, is interested in the arts. He grows his hair out like a hippie cuz he likes it, requesting undercover detective work because he’ll “fit in” with the counterculture scene as a result—then he’ll be able to work alone, rather than be partnered with some smirking nightstick.

While during the period depicted NYC was becoming notorious for crime and “urban blight,” Serpico doesn’t depict the city as some chaotically violent war zone, unlike myriad other 1970s movies from Little Murders to The Warriors. Drug dealing, break-in theft, and other matters are things its hero simply sees on the job. When he’s off the clock, he enjoys himself like any other Manhattanite, going to shows and parties, living with one girlfriend (Cornelia Sharpe), then another (Barbara Eda-Young in a large but rather thankless role), playing with his dog.

But when the embedded departmental corruption bothers him to a point where he feels he has to expose it, he’s driven near-mad by the puttering of higher-ups. They keep placing him at increasing risk, yet never make good on promises to commence an internal investigation. Out of desperation, he commits the Judas-like sin of approaching outside agencies, including the mayor’s office and eventually The New York Times. He’s well aware such actions could get him “accidentally” killed.

Written by Waldo Salt and Norman Wexler (both of whose scripts were selectively utilized during the summer ’73 shoot), Lumet’s film is a shaggy 130-minute biopic that seldom feels like a thriller, but whose unhurried pacing never feels slack, either. It’s tied together primarily by the magnetism of Pacino in his first real star vehicle, for which he got his first Best Actor Oscar nomination. (He’d skipped the prior ceremony, apparently incensed that at getting a supporting nom for The Godfather, when that film’s Marlon Brando actually won the big nod for a role with much less screentime.)

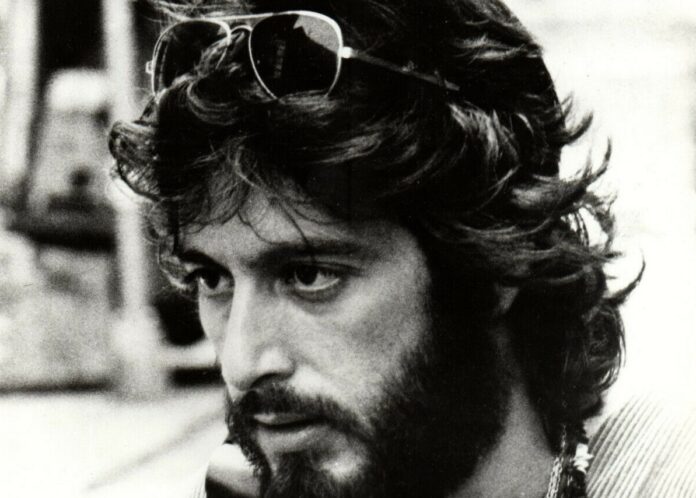

When Serpico eventually frazzles under pressure, we get a couple scenes of the actor yelling and throwing things around, going over-the-top in ways that would later become predictable mannerisms. But for the most part, he balances star turn and character with admirable conscientiousness, at once magnetic and self-effacingly low-key. He possibly never looked better than here, long-haired and bearded, eyes of a suffering Russian religious icon, but with a twinkle of hipster bemusement. He made Serpico the Billy Jack of 1973: An antiestablishment hero no longer at holy war with a redneck version of “the fuzz,” instead both against and with ‘em.

Police corruption of a different stripe is under scrutiny in Nancy Schwartzman’s Victim/Suspect, which begins streaming on Netflix Tue/23. The filmmaker, whose prior Roll Red Roll dissected one infuriating cover-up of a sexual assault case in an Ohio small town, casts a wider net this time to examine why such crimes frequently go unpunished. (It is estimated only one-third of sexual crimes get reported in the U.S., and only one percent are prosecuted.)

The answer is horrifying: She and investigative journalist Rachel de Leon discover a coast-to-coast proliferation of police disbelieving victims, using “bad cop” interrogation tactics to make them doubt their own experience, sometimes hiding damning evidence or declining to interview perps at all. Worse still, some women pressing charges against attackers end up accused, even jailed for “false reporting,” to life-ruining effect.

False accusations do happen—albeit rarely. As shown here, authorities’ bias against and intimidation of traumatized victims too frequently seems driven by a desire to protect the rapists, or simply reduce officers’ caseloads. Needless to say, all this has a chilling effect on such crimes’ reportage. Though there are scattered signs of positive institutional evoution, the stonewalling response the filmmakers get from various police departments here provides yet another illustration why law enforcement agencies should—like any branch of public service—be subject to external review. This infuriating but important documentary should be seen.

Managing to find a silly, escapist side to police corruption—not to mention women, sex, and the law—there is The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas, which Movies for Maniacs is showing alongside 9 to 5 at the Castro this Sun/27 in anticipation of next month’s Frameline festival and its inaugural Colin Higgins Youth Filmmaker Grant. Higgins (whose posthumous foundation funds those grants and other LGBTQ+ youth programs) was an actor turned scenarist (Harold and Maude, Silver Streak) turned director (Foul Play, which for better or worse made Chevy Chase a movie star.) He died of AIDS-related complications in 1988 at age 47, but not before writing and directing two more big comedy hits, both shown tonight.

Neither 1980’s 9 to 5 or the Broadway musical-derived Whorehouse are among the better movies of their era. But they were popular—in fact, the latter was the most successful traditional movie musical in a decade which perhaps represented that genre’s nadir. Dolly Parton (who’d made her big-screen debut in 9 to 5) plays the latest proprietress of a century-old bordello in the Lone Star State, while Burt Reynolds is the local sheriff as well as her secret lover. When a muckraking TV personality played by Dom DeLuise decides to whip up public moral outrage over this hitherto tacitly-tolerated institution, the hubbub eventually travels to the desk of the governor (Charles Durning, whose shifty-politician ditty “The Sidestep” is a bright spot).

Though daring for its title (which had to be fudged in some markets) and for being a rare R-rated musical (there is indeed some nudity), Whorehouse hews a little too closely to Dolly’s early lyrical boast that there’s “nuthin’ dirty goin’ on.” Admittedly, this contraption wasn’t much better onstage, but in Higgins’ film the strenuously uninfectious musical numbers feel trucked in from Knott’s Berry Farm, and the schmaltz lacks any conviction—Dolly’s 11th-hour dragging in of “I Will Always Love You” seems more insulting to her own songcraft than Whitney’s subsequent vocal bombast-strafing.

The stars apparently did not get along, though both do their damndest to look like they’re enjoying themselves (even if that effort makes Burt look even more tired). The raunch here is as antiseptic as 9 to 5’s low-cal sitcom feminism. Still, it’s a pity Higgins didn’t survive to demonstrate what he could do beyond the confines of the very mainstream features he completed. Their enormous popularity would have lent him a creative leverage he didn’t live long enough to exploit—perhaps one reason why he made sure his legacy supported upcoming gay and transgender talent.

If Whorehouse demonstrates the musical form at its most effortfully heterosexual (despite that football-team shower dance), you can get a corrective dose of diva excess with Funny Girl, playing this Wed/24-Thu/25 at the Vogue. It was 150 minutes of Streisand, Streisand, Streisand—hardly bowed by the weight of carrying her first movie, by the direction of three-time Oscar winner William Wyler (Ben-Hur), or the burden of impersonating stage superstar Fanny Brice in a biopic derived from another Broadway show by Gypsy’s brassy songsmith Jules Styne. The score remains imprinted on several generations of gay men and aspiring musical-theater performers’ DNA.

If Serpico in 1973 personified “New Hollywood,” Funny Girl five years earlier encapsulated Old Hollywood—which was definitely sweating the big changes afoot in audiences and culture, but still dominated the box-office. The year’s biggest hits were such artistically conservative constructs as The Odd Couple, Yours Mine & Ours (Lucille Ball and Henry Fonda in proto-Brady Bunch circumstances), costume epic The Lion in Winter, and John Wayne’s downright reactionary The Green Berets. More popular than any of them was Funny Girl—yes, more so even than 2001, Bullitt, and Rosemary’s Baby. It was also just about the only movie musical to do well (alongside Oliver!, released just a week later) amidst the glut of expensive bombs that ensued after the bonanza of The Sound of Music.

Barbra Streisand was instantly the biggest female star of the era, that status soon confirmed by Oscar (shared with Lion’s Katherine Hepburn in a rare split). Yet it as a bittersweet victory in a sense. Because even propped up by her outsized personality and following, the musical genre would still remain on life support—this smash screen debut was an anomaly, not a resurrection.