When you walk down the street in San Francisco, it is clear that homelessness is one of our most pressing issues. Yet sexual assault has largely been absent from the homelessness conversation. In reality, sexual violence, in all its forms, is deeply intertwined with the experience of homelessness.

Sexual violence is an overarching term that includes, but is not limited to, domestic violence, child sexual abuse, and sexual assault; sexual assault is a spectrum of nonconsensual sexual contact that ranges from verbal harassment to attempted and completed rape.

Jennifer Friedenbach, executive director of the Coalition on Homelessness and a longtime advocate for San Francisco’s homeless population, told me that sexual violence comes up in a lot of different ways in her work. One such way the intersection of sexual violence and homelessness is most typically discussed is the impact of domestic violence on women losing their housing.

Friedenbach explained that a lot of women become homeless fleeing physical and sexual violence. In fact, a 1997 study, which Friedenbach cited, found that 92% of homeless mothers experienced severe physical and/or sexual violenceduring their lifetime and 43% experienced child sexual abuse.

Clearly, sexual violence plays a part in homelessness.

What is less often discussed, however, is the role of sexual assault in the lives of homeless women. Friedenbach acknowledged that discussions about trauma from rape and other forms of sexual assault does not come up often in her work, but that it does come up in terms of homeless women sharing survival tactics. She describes that:

women will tell us that they prefer to stay in a tent because people walking by can’t tell what gender the person is inside the tent or if there is a knife waiting for them.

That feels a lot safer than sleeping exposed. We have a lot of women tell us that they don’t sleep at night so that they can sleep during the day to avoid sexual violence.

Whether or not these women experienced sexual violence before becoming homeless, it is unquestionably a part of their lives now. As the Connecticut Alliance to End Sexual Violence puts it, “…sexual abuse increases an individual’s probability of becoming homeless, and homelessness increases the risk of sexual victimization.”

Even though there may not be a causal relationship, the threads to sexual violence are everywhere and its impact is life-altering. This means that to address homelessness, we can no longer view sexual assault as a separate issue, but as one that further compounds the experience of homelessness.

How is San Francisco addressing sexual violence, and in particular sexual assault, in its efforts to combat homelessness?

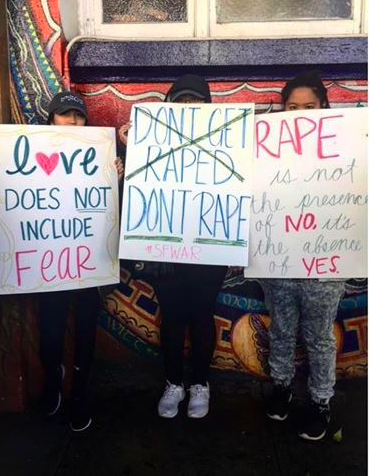

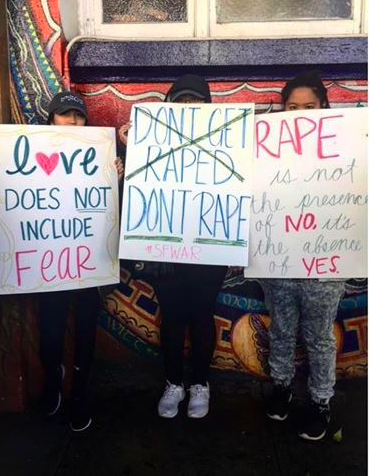

Friedenbach said that there has been some collaboration in the past. In particular, she says there has been work done between the Coalition on Homelessness and San Francisco’s rape crisis center, San Francisco Women Against Rape. The Mission Neighborhood Health Center, in partnership with the Women’s Community Clinic and Homeless Youth Alliance, runs a program called Ladies’ Night which SFWAR attends. Ladies’ Night represents a concerted effort to reach out to and support homeless survivors. Nevertheless, Friedenbach said she doesn’t know how homeless survivors experience the city’s sexual assault response system, since her organization has not focused on this conversation.

From my time as a sexual assault counselor in San Francisco, I can say that there are major barriers to providing rape crisis services to homeless survivors. For one, many homeless survivors don’t have regular access to a phone to even call a rape crisis hotline to initiate services. If they do gain access, the lack of housing and consistent contact information can make it extremely difficult to connect homeless survivors to additional services. Similarly, homeless survivors who do somehow make it to San Francisco General Hospital for medical services in the immediate aftermath of their assault face the same challenge in receiving the follow-up required for continued support.

Obviously, many homeless survivors’ major concern in the hours following their sexual assault is having a safe place to stay that is free from more sexual violence. This brings up a crucial conversation about shelter access for survivors of sexual assault and survivors of domestic violence.

Friedenbach told me that shelters for domestic violence survivors are very specific. If the person did not experience intimate partner violence, then they are not able to stay at that shelter. However, as Friedenbach explained, this construct doesn’t really work for women who are without housing; a woman whose home is on the street experiences proximity to sexual violence in the same way she would if she lived in an actual home with the offending partner.

Typically, women are waiting for five to six weeks for a bed to open up according to Friedenbach. She said women seeking shelter should never be turned away because the safety issues are too profound. The Coalition on Homelessness has always fought for continuing to have a 24-hour drop in shelter, that Friedenbach says exists now through A Women’s Place Drop-In Center.

San Francisco needs to confront homelessness in its efforts to combat sexual violence just as much as it needs to confront sexual violence in its efforts to combat homelessness. Conversations and policy reform concerning the city’s response to sexual assault should include advocates for the homeless population, and vice versa. To do so, San Francisco should consider asking advocates from homeless service provider organizations to join the Sexual Assault Response Team. This should be done in order to better coordinate services for homeless survivors and build a more comprehensive system that is accountable to homeless survivors.

It’s obvious to me as a sexual assault counselor that trauma from sexual violence – whether that be domestic violence or sexual assault — has a lasting impact on people’s ability to live and work. It impedes one’s ability to get up in the morning, to execute a job well, and to carry out the never-ending responsibilities of being an adult. At times, I’m sure we all feel we are barely keeping afloat in the rushing river that can be our lives. Add deep trauma from a violent sexual assault on top of the uphill battle San Franciscans face in maintaining a sustainable livelihood – it is no wonder people are sinking.

If you are disturbed and moved to action by homelessness in San Francisco — and I hope you are — you should be moved to end sexual violence in our city as well.