Singer-songwriter Tori Amos is quick to applaud the first responders—the doctors, nurses, and EMTs—who are currently risking their lives to save others during the coronavirus pandemic.

But the “Silent All These Years,” “Cornflake Girl,” and “Spark” singer told 48 Hills that after the darkest days of COVID-19 have passed, it will take a second round of responders—the artists and writers—to give voice to our collective pain and, in so doing, begin a second wave of healing.

Amos is used to creating meaningful art in response to extreme personal and political traumas. Her 1991 single “Me and a Gun,” about being sexually assaulted, shed a light on the rape epidemic. Her 2002 album Scarlet’s Walk was a response to the devastation that befell the nation in the wake of the September 11 attacks and 2017’s Native Invader was a reaction against the politics of hatred that swept the country after the 2016 United States election. Her foray into theatre with the 2013 stage musical The Light Princess, a feminist take on the classic fairytale, confronted widespread sexism and misogyny.

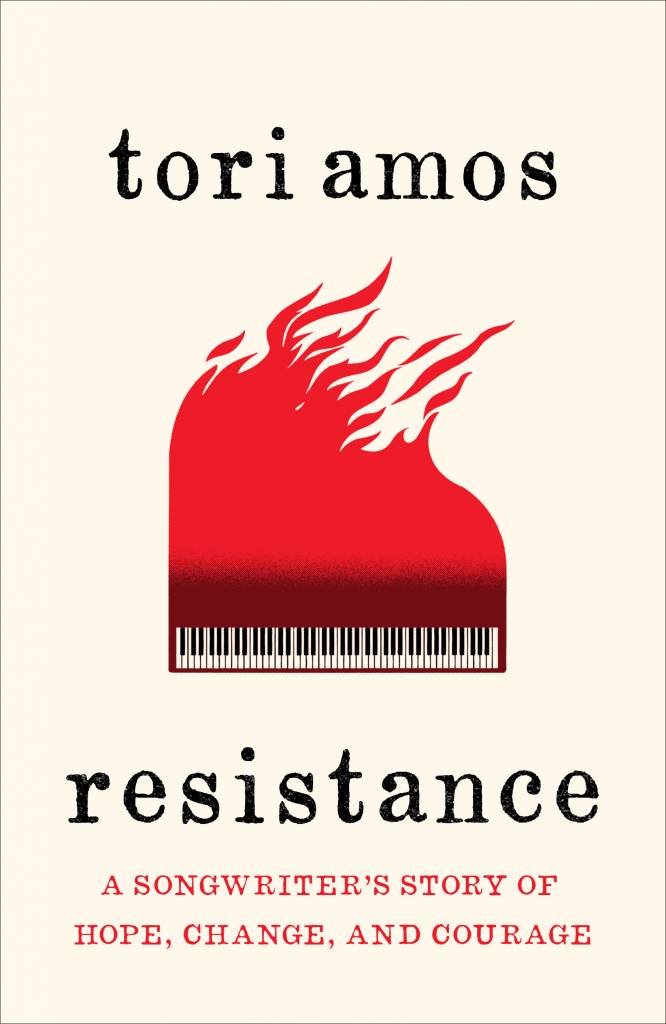

Drawing from her creative highs and lows, the experiences that inspired and shaped them, and the life lessons she’s learned along the way, Amos’s riveting new book released May 5, Resistance: A Songwriter’s Story of Hope, Change, and Courage, offers her fellow artists a blueprint for similarly pushing back against “patriarchal power structures” through art.

Tori Amos spoke to me last month from her home in Cornwall, in the South West of England, about art as a form of political resistance, her biggest artistic crisis, and how her fans continue to inform her music.

48 HILLS In Resistance, you describe the ways in which art can be an antidote to personal and political traumas. How, in your opinion, should artists be using their mediums amid the current pandemic?

TORI AMOS Once the doctors and nurses will have done such an incredible job in healing people physically, the writers and artists are going to need to be a healing spiritual and emotional balm.

I do think there will be art coming out from all kinds of artists that will express what we’re hearing at this time from what people are going through. There is a value to that and it will be needed after losing people and the grief of that. Art, like Irish Keening—where the keeners go up and sing into your ear to bring up things with their voices and their music that you’re feeling but haven’t been able to express—is important. So I absolutely believe that the artists are going to have an important role to play.

There’s a value in storytelling, so I just want to encourage artists because they are needed. We need to feel the calling. Some days I have a good cry and then it’s like, “Dust yourself off, Tor. Come on back to the piano and let’s channel this.”

48 HILLS In the book, you describe a time, early in your career, when you were chasing commercial success instead of producing music that was meaningful to you. What did you learn from this experience?

TORI AMOS I chose to believe the business suits over the piano and the muses, and that’s where I found myself at a huge artistic crisis in my mid-20s. I really then had to crawl back to a place where I asked myself that question that really smacked me back to life, “How do you go from prodigy to bimbo?”

And so there was a whole kind of grieving that had to go on and responsibility. I had to see my part in it. I made those choices. I couldn’t blame anybody else. The piano forgave me much quicker than I forgave myself, but then I never betrayed her again. The gift was I’ve been able to stand my ground because I know what it feels like when I betray her.

48 HILLS One of the most powerful chapters in the book was about how 9/11 shaped you and your subsequent tour and album. What did you learn from that experience that serves you as an artist today?

TORI AMOS Wow, what a question. Doing the Strange Little Tour after 9/11 when a lot of artists were being encouraged to cancel, there were a few things I learned. When [John Lennon’s] song “Imagine” was being banned on the radio because the drums of war were raging and nobody wanted the narrative of “Imagine all the people living life in peace,” I learned that some songs can be “dangerous.”

Also, people were coming up to me and saying my music is really a backdrop to gather, share intel, and get to the truth. Artists owe it to their audience to listen to what they are saying and channel that into their work. Art had to imitate life, so I wrote Scarlet’s Walk on the Strange Little Tour. Just like my next record is changing because of what’s happening now. Some people are talking about losing their freedoms and when the virus is gone, will all those freedoms come back? So there’s a lot to think about.

48 HILLS In Resistance you explain how meet-and-greets and reading fan mail inspire the subjects that you tackle in your music. Should more artists be doing this?

TORI AMOS Look, they are my intel. I trust them more than the CIA. There are hundreds of letters and it takes time to go through them, but I’m always amazed at what I learn from them. It’s not always tragic stories where you learn, but also you learn from somebody just sharing what they’ve learned, like, “I learned this today where I was working at a coffee bar,” and you go, “Wow, you’re my Buddha at this moment. That’s just wisdom.”

So I can’t get my head around it when I show up at a venue and someone at the door goes, “Most stars don’t [talk to their fans]; they don’t have that relationship.” I don’t know what crap they’re smoking, but then the gold is falling through the cracks because that is the magic right there.

48 HILLS Several artists have been “cancelled” for complaining on social media about how the shelter-in-place order has impacted them — when they’re already so advantaged. How does an artist find the balance between expressing themselves and coming off as insensitive right now?

TORI AMOS Wow, that is a good question. Getting that balance right is… sometimes certain artists aren’t about balance. Certain artists can take this to extremes because that’s their craft. So I feel like if it’s coming from a genuine place of expression, then people need to express themselves right now.

If you’re a non-artist, you might be feeling something similar but don’t have the platform, so so many emotions are coming up and so many issues are coming up, such as issues of control. We’re in a controlled state of being right now. When someone might say, “If you look at it like a Buddhist retreat,” my grumpy British husband might say, “I’m not in a Buddhist retreat. I’ve got a full house with two vegans and two non-vegans. I wish I could be alone. So anyone who’s lonely, trade places with me and sleep with my wife.” [Laughs]

48 HILLS What can non-artists take away from your book?

TORI AMOS For those who don’t see themselves as creative, I wanted to write a book that talks about the process and takes the lights and the makeup off of some of it, so they could have a relationship with art in a different way, so that it’s not an “us and them” kind of thing.

I really wanted to expose my personal struggles as an artist, so people who care about artists can understand it and how sometimes the only way out of the struggle is to create toward it and with it.