Joe Dante was one of numerous filmmakers who made a name for themselves in the realm of independent exploitation cinema in the 1970s, then graduated to the Hollywood mainstream in the ’80s—Tobe Hooper, Wes Craven, John Carpenter, John Landis, and others. A born cineaste, he began compiling the epic mega-midnight show “The Movie Orgy” (consisting of old TV, serial, drive-in feature, cartoon, industrial and additional miscellaneous clips) while an art school student in the late ’60s; an ever-changing entity that at one point was 7.5 hours, it became its own kind of legendary viewing experience.

That led somehow to working for Roger Corman, the B-movie king and starter of many such careers (including Coppola and Bogdanovich earlier), who eventually let him co-direct the 1976 cult comedy Hollywood Boulevard, then solo two years later on the tongue-in-cheek Jaws knockoff Piranha, written by John Sayles. That in turn led to 1981’s The Howling, an equally witty spin on werewolf lore, by which time he had the attention of Steven Spielberg, who put him in charge of what’s probably the best segment in 1983’s Twilight Zone: The Movie. It would prove a defining moment for Dante, underlining his antic fanboy sensibility as laying halfway between Fangoria and Looney Tunes. (Indeed, 20 years later he’d direct the mixed live action/‘toon feature Looney Tunes: Back in Action.)

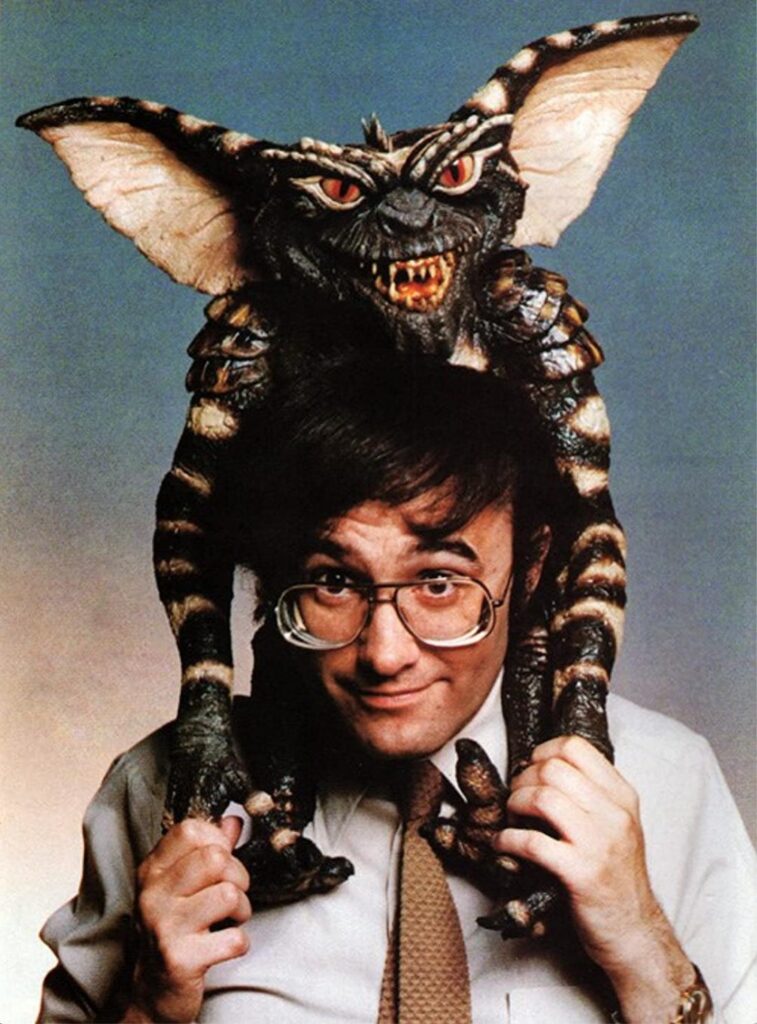

This Sat/16 at the Castro Theatre, Movies for Maniacs (no longer Midnites for Maniacs, but still the domain of our colleague Jesse Hawthorne Ficks) will be presenting in conjunction with that venue’s new owner APE “A Genuine Tribute to Gremlins and Gremlins 2.” Those are the movies that bookended Dante’s fairly short stint atop the major-studio talent pile—like the peer directors mentioned above, he was gradually less in Hollywood’s fickle favor when the ’80s were over. But he’s stayed busy (mostly via TV projects in recent years), and mention of his name still lights up the eyes of anyone who was a regular multiplex or cable viewer in that era.

Gremlins was, like Hooper’s Poltergeist two years before or Dante’s own Explorers a year later, a PG fantasy very much informed by the ginormous success of executive producer Spielberg’s E.T.—a little scary, a little sci-fi, but still cute, and family-friendly… well, sorta. Written by future Home Alone and Mrs. Doubtfire director Chris Columbus, it found various squeaky-clean suburbanites (notably teens Zach Galligan and Phoebe Cates) in possession of adorable furry “mogwai” pets who regrettably turn into malevolent monsters when exposed to water, or fed after midnight.

The secret sauce to Gremlins was, unmistakably, Dante: He pushed a potentially innocuous whimsy to the brink of real horror, to an extent that some found too alarming or vicious for the younger viewers being lured in. But that edge also lifted it partly out of already-familiar Spielbergiana into something more distinctively black-comedic. The result may have been a bit too much for some, but not for many: Gremlins was one of 1984’s biggest hits, beaten at the box-office only by Beverly Hills Cop, Ghostbusters and Indiana Jones.

After the interesting but commercially disappointing sci-fi of Explorers and Innerspace, as well as black comedy The ‘Burbs (plus some fine episodic work), Dante returned to the scene of the crime with 1990’s Gremlins 2: The New Batch—one of those movies so beloved since, you can’t quite believe it was originally something of a flop. He and scenarist Charles S. Haas got the go-ahead to cut loose with what seemed a sure-fire prospect, and they did, using this sequel to not just amp up the slapstick-horror elements, but also ruthlessly send up popular culture (it’s set in a cable network’s high-rise HQ).

With real roles for everyone from Christopher Lee to Dick Miller and Paul Bartel, cameos likewise (Hulk Hogan, Leonard Maltin, Dick Butkus, etc.), Looney Tunes character segments directed by Chuck Jones, and an avalanche of movie in-jokes, G2:TNB was a born cult object—one maybe too clever for the masses. (It even parodied Donald Trump with a blowhard tycoon called Daniel Clamp.) It was not the anticipated hit. Nor was Dante and Haas’ next project, the 1950s drive-in movie homage Matinee, despite critical admiration. The director did make bank with the alterna-toy story Small Soldiers (1998), but by the millennium it seemed his quirky sensibility was welcome mostly on the small screen, or in smaller-budgeted features.

Dante and Haas will be on hand to introduce Gremlins 2 at 9pm, while the former will participate in an interview/Q&A session after the 6pm screening of Gremlins, which will be shown in a rare 35mm “preview version” apparently containing scenes cut from all subsequent regular releases. Dante will also be available for autograph signing on the mezzanine as of 5 pm. For tickets and more info, go here.

(P.S. It will probably surprise no one to learn that there is reportedly a Gremlins 3 in the works, apparently sparked by the popularity of a gremlins-related Mountain Dew commercial last year, plus the imminence of a spinoff HBO cartoon series.)

Fittingly, this week also brings a number of new releases in the realms of fantasy and horror, though most take themselves quite a bit more seriously than Joe Dante is usually inclined. They also underline one thing that’s changed a great deal since the original Gremlins era: Women directors and women-driven narratives are a lot more prominent among genre films now, and I don’t mean “Final Girl running around screaming in a wet T-shirt,” either.

Probably the most interesting among them stylistically is Charlotte Colbert’s UK debut feature She Will, which stars the always-compelling Alice Krige as an imperious grande dame with a slight Norma Desmond aura. Having just undergone a double mastectomy, she journeys with her put-upon young nurse (Kota Eberhardt) to a “retreat” in the Scottish Highlands that is not at all what she anticipated. Nonetheless, they stick around, each differently intrigued by the mysterious, purportedly “healing,” sometimes hallucinogenic properties of a site where women were once burnt as witches.

Handsomely shot, rather rich in atmospheric texture, She Will is more murky and slight in scripted substance. It introduces intriguing subsidiary characters, then fails to do much with them, a pity since they are played by such impressive talents as Rupert Everett, Malcolm McDowell, and Olwen Fouere. Still, the leads give it their all, and Colbert has given them an aesthetically arresting if not fully satisfying vehicle to excel in. IFC Midnight is releasing to limited theaters and On Demand platforms Fri/15.

Equally striking in a more tersely controlled, slow-burn mode is Jenna Cato Bass’ South African Good Madam. After a falling out with other relatives, hot-tempered Tsidi (Chumisa Cosa) lands with her little girl Winnie (Kamvalethu Jonas Raziya) on the doorstep of her mother Mavis (Nosipho Mtebe), who takes them in. But it’s a complicated situation, because this isn’t Mavis’ house—indeed, she let Tsidi be raised by others while she devoted her life to serving the white “madam” now apparently bedridden upstairs.

Tsidi rarely visited here, but she has bad memories. Now they seem to be surging back, along with visions of things that may not have happened, or have yet to. Is Tsidi losing her mind? Is the house—and its legacy of racially divided service/servitude—somehow claiming her? Is the old mistress even alive? Is she a ghost, or some kind of life-sucking wraith?

Good Madam starts out looking like it will be an imitation of Get Out, but it has other things on its mind, even if they get rather fuzzily articulated. Wee Winnie aside, none of these characters are very likable; the political-historical subtext will be a lot more obvious to South Africans. Nonetheless, if it frustrates on some levels (and will irk those looking for lots of overt horror content), Bass’ film has a precision of execution and evocative feel that are quietly unsettling in a memorable way. It’s available on streaming platform Shudder as of Thurs/14.

Another house of women under threat is the Glasshouse of Kelsey Egan’s first feature, another South African production. It’s set in a dystopian future that looks like a colonialist past: A virus known as “The Shred” has decimated most human and animal life with its memory-decimating virus, but the residents of the titular old-fashioned greenhouse they call The Sanctuary wear bonnets and muslin dresses as they sing English folk-type songs in over-refined voices. It’s all very Picnic at Hanging Rock meets Flowers in the Attic, with Mother (a rather hammy Adrienne Pearce) stern keeper of the collective mythology for a flock of three young girls and one Shred-afflicted teenage boy.

As in the various versions of The Beguiled, this polite if tedious tea-time seclusion is interrupted by the arrival of a Real Man, when eldest daughter Bee (Jessica Alexander) fails to shoot on sight an intruder (Hilton Pelser). Though wounded, he is apparently immune to the general contagion. He is reluctantly taken in, tended to, and put to work—including, well, the work of assisting procreation. But needless to say, Dude party-crashing Matriarchy = Trouble.

The “epidemic that wipes out most of humanity” hook was getting tired even before COVID, and Glasshouse doesn’t bring much new to the table beyond pretty aesthetics, pretension, and sloppy internal logic. Shot at the 140-year-old Pearson Conservatory in Port Elizabeth, it wasn’t my cup of twee. But it has won some fans of the genre-festival circuit, so it may well be yours. Glasshouse is available on US digital and On Demand platforms as of Tues/12.

Very much set in the here-and-now is Diego Fried and Federico Finkielstain’s Argentinian The Silent Party, which offers a somewhat more blunt critique of the class, gender and other divisions probed by the films above. Laura (Jazmin Stuart) and Daniel (Esteban Bigliardi) are introduced quarreling on a long drive—en route to her family’s ranch, where they’ll be married, which doesn’t seem a great idea. Nor does her boorish, gun-wielding father (Gerardo Romano) inspire much confidence.

Still, things don’t really begin to boil over until Laura goes for a walk, intending to cool down her irked mood. She stumbles upon a nearby outdoor “silent party” where she’s given her own set of headphones for dancing, and a drink that is very possibly spiked. Soon she’s really, really getting into it, booty-shaking leading to sex with strangers that afterwards she’s not at all sure was consensual. When she recalls enough to decide it wasn’t (at least not entirely), she is furious—leading to reckless actions that soon also involve the fiancee and trigger-happy dad. Needless to say, whatever hasn’t already spiraled out of control then rapidly does.

Well crafted, The Silent Party plays insidiously with the notion of consent, leaving no one entirely innocent—or sympathetic. While none of these people is entirely bad, they all behave badly, their degrees of complicity keeping them from calling the cops as they should have done in the first place. It’s a skillful movie, but in the end more simply misanthropic than it is clever, ironical, suspenseful, or pointed as social commentary. Outsider Pictures is releasing it to US streaming platforms (including iTunes, Amazon, Vudu and Google) as of Tues/12.

On the other hand, it’s the very soul of conscious storytelling compared to a relic of retro exploitation cinema like Fair Game, a 1986 Australian joint that Tarantino is a fan of, and which purportedly influenced his “Death Proof” (the second half of Grindhouse). Cassandra Delaney plays Jessica, an outback babe who lives in a wildlife sanctuary with her husband. Unfortunately, he is away on a road trip when she begins being terrorized by three itinerant goons (Peter Ford, Garry Who, David Sandford) who graduate from poaching to human-hunting in a hurry.

A first narrative feature for Mario Andreacchio, who later worked mostly in TV and family entertainment, Fair Game is energetic trash; you can see why it might have cult appeal to someone like QT. There are elements of Mad Max, Razorback, I Spit On Your Grave (rather oddly minus the rape element, though Delaney gets run through every other kind of mill), Straw Dogs and The Most Dangerous Game. It’s loud, giddy, not high on plausibility, with lots of structures apparently built from popsicle sticks (so vehicles can crash through them), and the requisite ’80s soundtrack of dumb synth-rock. It’s over-the-top, all right. But it stays there so long, things get kinda monotonous.

It doesn’t help that the lead actress (who soon left the profession to become John Denver’s wife, strangely enough) is made to look silly even when her character is resourcefully resilient, forever squealing and running through the brush as if in high heels. I enjoyed a few yoks, but felt kinda soiled nonetheless. (For what it’s worth, the director now says he always meant the film to be a “cartoon,” though that smacks a bit of Tommy Wiseau claiming The Room is intentionally funny.) The biggest laugh came at the end, when everyone is dead but our heroine, and she triumphantly fluffs her hair as a closing power ballad exults “Now stars are in my eyes instead of tears/I can fly! Fly so high!/And this feeling inside makes me glad I’m alive!”

If Fair Game remains more watchable than it should be, one can probably largely credit the participation of late cinematographer Andrew Lesnie, who’d go on to shoot most of Peter Jackson’s larger-scale films, and win an Oscar for his first Lord of the Rings installment. Dark Star Pictures releases it to US On Demand platforms Tues/12, with Blu-rays and DVDs available next month.