Timing is a funny thing: the day before I visited Berkeley to see this exhibit, I was part of SF’s freeway-jamming ceasefire demonstration, organized by Jewish Voice for Peace. The people of Palestine are as victimized by colonization as any other group under occupation, and walking beside them in that protest was one of the more life-reaffirming activities I’ve done this year. So, when I wound up at this exhibit the next day and saw Duane Linklater’s canvas with the painted words “Custer had it coming,” it struck my anti-colonial heart in all the right ways.

That piece, titled Boys Don’t Cry, was actually the final stop on our curated tour of mymothersside (runs through February 25 at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive). Of First Nations heritage, born into what is now Northern Ontario, Canada, the Omaskêko Cree Linklater’s work explores his birth land, both before and after European colonizers planted stakes on its sacred soil.

With that running theme of homes past and present, I suppose it’s appropriate that much of the installation involves deconstructions of the tipi. Although the installation is open to any BAMPFA visitor during regular hours, one can check the museum’s website for their infrequently-scheduled tours of the exhibit. The first stop on the tour (the day I went, we had a rather aloof docent leading us) is the 2015 piece dislodgevanishskinground. It features 12 tipi poles jutting out from a wall, each slanted to meet at a point near their tips, its linen exterior (used for the piece in lieu of traditional buffalo skin) hangs from the point at which the poles meet. It looks as if the tipi had been put on its side and began to float in midair. We’re told that Linklater was tapping into the literal and figurative sense of dislocation people have under colonialism—as if their whole world had been turned on its ear.

This carries into the next piece, wintercount (No. 215), in which tipi linens hang like drying laundry, except there are noticeable markings against the earth tones of the linens. We’re told that the seemingly random dark markings have two meanings: first, representing just a small number of the First Nations lives lost to Canada’s infamous residential school system; and secondly, the Lakota calendar. The piece’s title comes from the Cree method of counting a person’s age, “How many winters have you had?”

In fact, the exhibit’s name also alludes to how the Cree, like most Indigenous groups, had no written language. They have one now, though it’s relatively “new” compared to the written Germanic-derived scripts (English, French, Italian, etc.) or those of greater Asia. Mashing the titles of the show’s pieces together into singular words imitates the syllabic speech pattern of the Cree’s spoken tongue, one part directly leading into the other.

The importance of language in its many forms stands out in the piece What Then Remains, the latest entry of a series permanently installed in institutions all around the country. As in other editions, this one required the hosting building to remove a piece of the wall to expose the supportive materials underneath. With just a little red paint, Linklater painted the support beams to make them (sorta) spell out the piece’s title. (I say sorta because supportive beams don’t form into a traditional English alphabet. What’s “written” in red paint is more akin to ad hoc words written on a seven-segment display.) And, as with earlier editions, the paint is expected to remain on the beams long after the wall proper has been restored, leaving a permanent mark of Linklater’s contribution.

Two videos from his Cape Spear series are shown, one of which features the aforementioned cape, uninhabited. The cape was once home to a tribe that lived at one of the furthest northeast points in North America before settlers expeditiously declared them “extinct.” We’re told Linklater’s encounter with surviving members inspired the series, with the Zen-like footage of water hitting rocks suggesting ghosts remaining in a confined area, though that’s probably my own takeaway from the description.

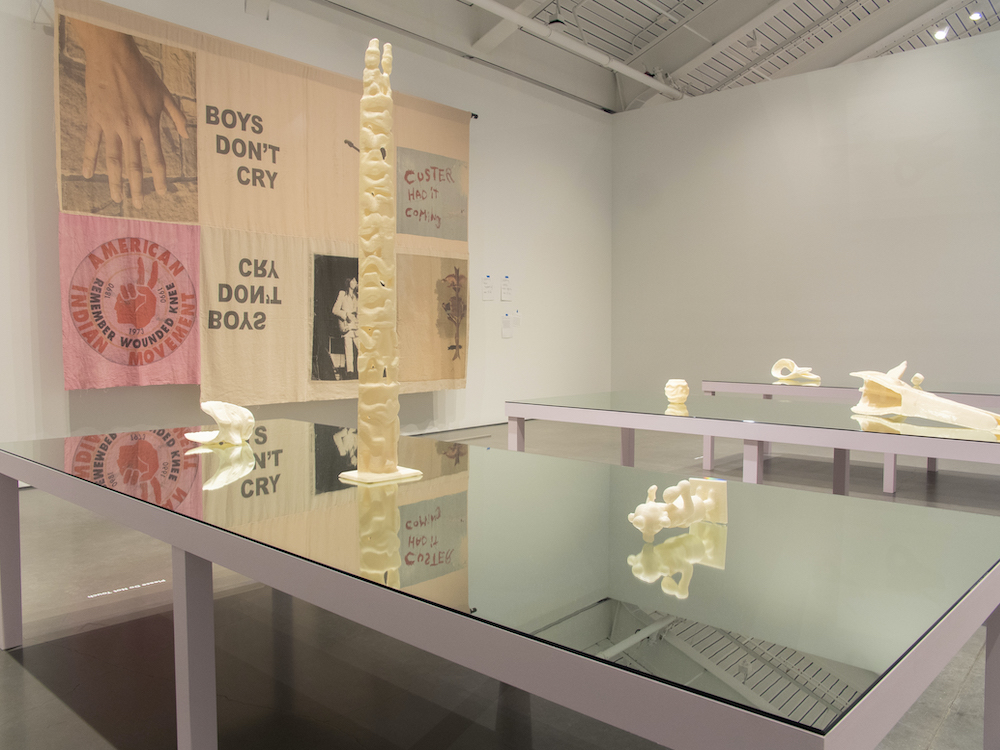

The tour ends with a few mirror-covered tables displaying 3-D-printed recreation of First Nations artifacts from the Utah Museum of Fine Art. On the wall near the tables is the aforementioned Boys Don’t Cry. The latter is the end of a trail of several clothing articles found throughout the tour. All the clothes were Linklater’s in his adolescence, and Boys Don’t Cry represents an adult recollection of how the young artist tried to process his identity; challenging ideas of white colonialism and universal displays of toxic masculinity. Indeed, the Cree heritage is matrilineal, taking pride in one’s connection to the feminine, despite one’s specific gender identity.

Help us save local journalism!

Every tax-deductible donation helps us grow to cover the issues that mean the most to our community. Become a 48 Hills Hero and support the only daily progressive news source in the Bay Area.

Absentmindedly, I’d forgotten my Aranet4 at home and was unable to take CO² readings at BAMPFA. Still, even as the only person masked (save for one custodian I saw afterward), the small size of my tour group combined with the wide-open space of the facility let me focus on taking notes more than worry about infection, especially as I was always able to put space between myself and the others.

Our novice docent notwithstanding, walking through mymothersside was a relaxing 30-or-so minutes on my first-ever trip to BAMPFA. It perfectly complemented the pro-Palestinian demonstrating I’d done just the day before. Like the Cape Spear tribe, Palestinians are already being declared extinct as they ask for nothing more than the right to live freely. mymothersside is a testament to the resilience of a colonized people who refuse to vanish like ghosts.

DUANE LINKLATER: mymothersside runs through February 25 at Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. Tickets and more info here.