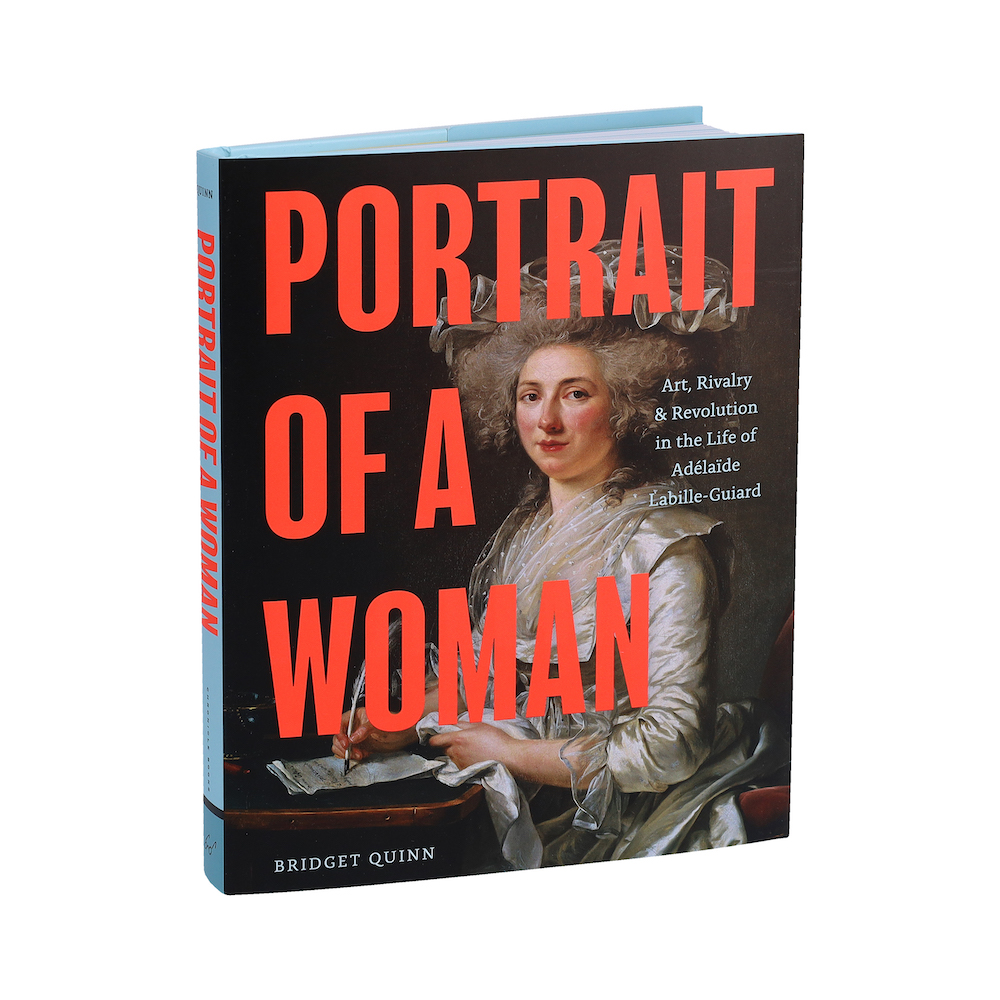

While reading Bridget Quinn’s marvelous new biography, Portrait of a Woman: Art, Rivalry & Revolution in the Life of Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (Chronicle Books, $29.95), it’s tempting to think of the French portraitist born in 1749 as a woman ahead of her time.

Don’t. Yes, Labille-Guiard defied the conventional forces of 18th century society that quashed women in multiple ways. But arguably, the story of her life proves Labille-Guiard was exactly suited to what women and the world of art needed in the late 1700s. She heralded a new era in art history, masterminded the marriage trap to her advantage, and supported the work of other women artists instead of beating them back as competitors.

Indeed, if it were not for Labille-Guiard, would there have been a Mary Cassat, Frida Kahlo, or Georgia O’Keeffe? And would Élisabeth Vigée-LeBrun, her Académie Royale counterpart, have risen to such heights if not for their supposed rivalry? Certainly, the work and life of her biographer, Quinn, would not have been the same had the Bay Area-based writer not happened upon Labille-Guiard’s paintings while pursuing a PhD in art history at the Institute of Fine Arts in New York City.

Fumbling around for a research topic, Quinn saw a slide of Self-Portrait with Two Pupils and learned the original art was nearby at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Thus began a more than three-decade relationship with Labille-Guiard, one so intimate that Quinn refers to her subject throughout the book as Adélaïde and writes, “Having spent the majority of my adult life with her, I like to think that at this point we are on a first-name basis.”

Quinn is the award-winning author of She Votes: How U.S. Women Won Suffrage, What Happened Next, and Broad Strokes: 15 Women Who Made Art and Made History (in That Order). Raised in rural Montana amid cows and nuclear war silos, she has taught art, history, and writing, worked in museums and galleries, become a sought-after speaker on women and art, and is an avid outdoor sportswoman.

The subject of her book’s 25 chapters is accompanied by 26 epistles that quote from Vigée-LeBrun’s three-volume memoir in letters, Souvenirs. As Quinn writes, there is no hero without an antagonist, and the more-famous Vigée-LeBrun serves here as a perfect foil, with her letters carrying a tone of privileged superiority. Sadly, Labille-Guiard was too obsessed with painting to write often, and her artwork and few written materials were burned in the French Revolution or otherwise lost.

What remains to us is Labille-Guiard’s dramatic life story. The glorious writing of Quinn is evidence of their shared heritage: self-deprecating sense of humor, love of research and craft, and fearlessness when it comes to revolutionizing their industries.

I have never before had a favorite chapter in a book—or at least, I’ve not admitted to it publicly—but Chapter 17 best displays a great art writer writing about great art. Seven close-ups culled from Labille-Guiard’s self-portrait are brought to life in swoon-worthy words that invite a reader to not just view, but to inhabit the artwork.

A conversation between 48hills and Quinn begins with her experience writing about Self-Portrait with Two Pupils.

“That painting I first saw when I had just turned 22. I visited it almost every day for years. Having looked at it thousands of times, it’s crazy I can still see something new,” she says.

Visiting the Met just prior to the pandemic, Quinn noticed for the first time that Labille-Guiard shows her teeth. Aristocratic dictums of the time disallowed exposed teeth in portraits and considered the practice crass and only suitable for the lower class. “How could I not notice that? I was always circling around it. Seeing it as an older person meant I slowed down. I had also read a book about 18th century teeth written by a dentist. I had never realized and was shocked that artists had been mocked for showing teeth in portraiture.

“I was able to look at the painting and see what’s actually there. The teeth, the worn, battered floor, the shine of her dress, the open paint box in shadow and that big lock—time deepened the looking.”

The people in Labille-Guiard’s portraits appear animated, as if they might at any moment walk right out of a painting and say “good evening.” In contrast, subjects in portraits of other artists sometimes appear staged, more like elements in a still life. Quinn says, “It’s the difference between an advertisement and an image you would cherish of someone in your family. It’s how much they reveal their soul or personality or whatever is tender. Labille-Guiard has a big heart without being sentimental, including about herself. What shows in her paintings of friends is that she cares about them.”

Quinn’s experience of living with such a painting for over 30 years and eventually writing this biography was expectedly lengthy. She confesses, “It wasn’t easy. Especially the middle; things can sag. The French Revolution provided obvious conflict and climax, but the hardest part was telling a story of the world of French art with its own language, politics, styles. How to treat those things without beating a reader over the head. I used all the storyteller’s tools: character, conflict, the senses. I wrote more than 1,000 pages to figure out the final 300 pages. It was an epistolary time in the 18th century, so the memoir runs Adélaïde’s story alongside the letters of Vigée-LeBrun.”

Writing biographical histories invites the risk that readers will think of an era or person as pinned in the past and irrelevant to today. “What more obvious comparison is there than of this time when women had status and power in society and could rise to the highest levels of art and politics and yet, all of it could be taken away, as is what happened after the French Revolution?” asks Quinn. “To see Roe v. Wade overturned in our time, it’s chilling. We look at history as an ever-evolving march to greater freedom and that’s not true.”

Notably, the definitions of 18th and 21st century feminists Quinn states are the same. “Art feminists believe women have equal rights with male artist. There is no quota on the women ‘allowed’ into the greatest theaters of art. Only actions matter and Adélaïde spoke out for the rights of all women artists.” She says the most rewarding aspect of writing Portrait of a Woman is how the magical retelling of a past story can change the present, and holds the potential of altering the future.

Buy Portrait of a Woman here.