This past Saturday, while hundreds gathered in Golden Gate Park to pressure the city to keep cars off JFK Drive, a few dozen Bayview protestors asked once more for the City to remove radioactive waste from their doorstep.

“The Tetra Tech scandal was a tipping point,” Kamillah Ealom, BVHP Program Community Organizer for Greenaction for Health and Environmental Justice, said—citing the massive 2019 fraud case involving the cleanup of Hunters Point Naval Shipyard, the country’s largest superfund site. “We know stuff was there. It was a cover-up.”

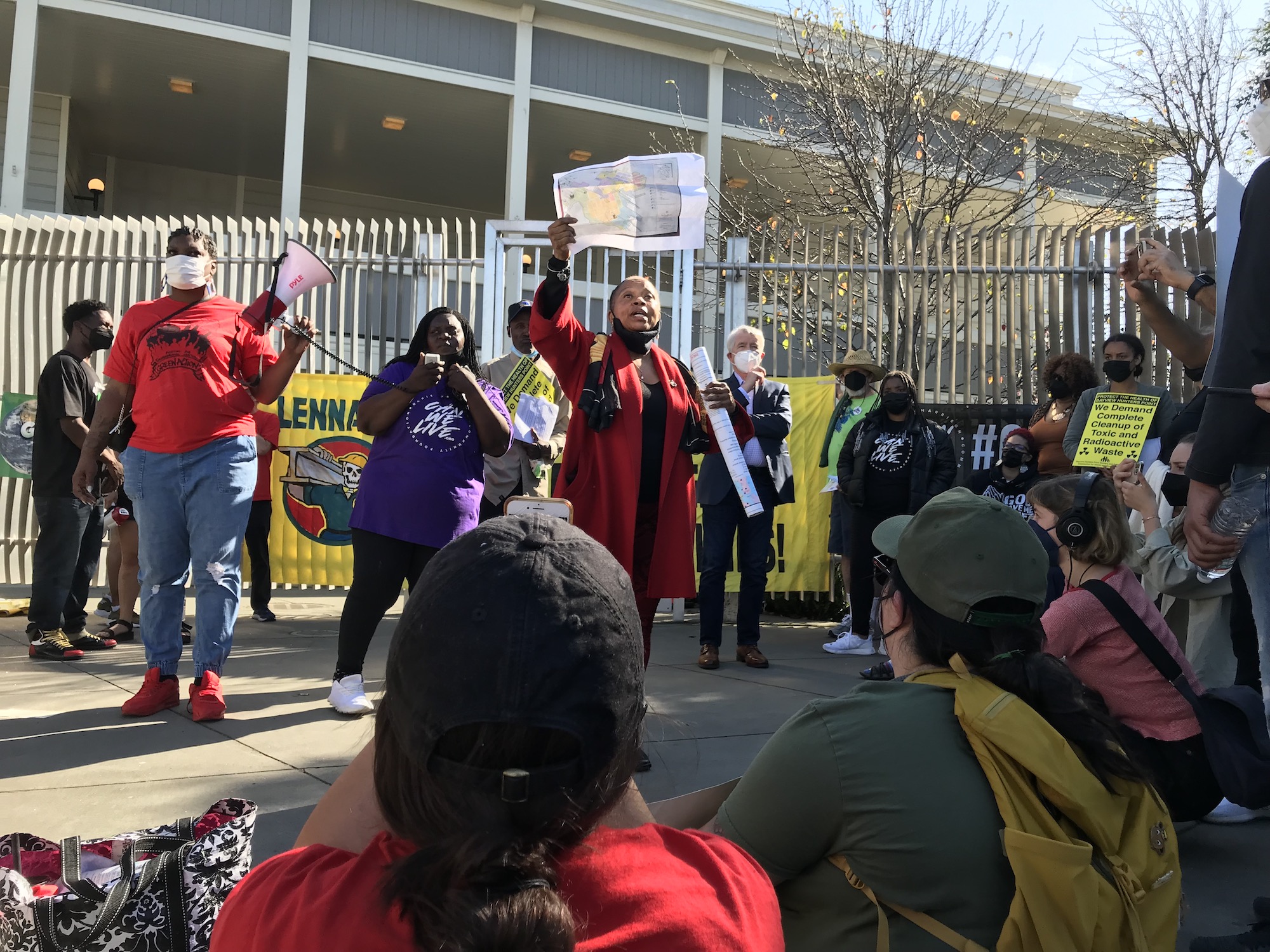

Saturday’s protest, complete with bull-horned Gospel songs of “Satan We’re Gonna Tear Your Kingdom Down” and posters like “Stop Cancer Where It Starts: Pollution,” began at noon on Third and Evans. But the fight to clean up the shipyard started generations ago and remains one of San Francisco’s most powerful but buried stories. And that story is intertwined with San Francisco’s Black history.

Recruited from the south in the 1940s to the shipyards to aid the war effort, the Black population in San Francisco rose from around 5,000 just before the war to 32,000 by 1945. Part of the “Great Migration” astutely chronicled by Isabel Wilkerson in her Pulitzer-Prize winning Warmth of Other Suns, this seismic cultural influx created Fillmore’s legendary “Harlem of the West” and brought global influencers to San Francisco such as Maya Angelou and Bill Russell.

When the war ended and the base eventually closed, the Bayview community lost their financial footing in one fell swoop. The protestors on Saturday were living with that legacy, as well as the contamination left by the Navy and the pollution churned out daily within the Bayview.

Ealom, “born in SF General 43 years ago, raised in the Bayview and living in Alice Griffith,” knows the history well. She feels a “duty to educate and mobilize and galvanize my community to know we are surrounded by pollution.”

“We want a deep survey, with excavation and removal of any radioactive residue,” Ealom said. “And this time, because of the Tetra Tech scandal, we’re demanding community oversight of the process to insure we have a full clean-up of all the contamination.”

Although the demand is not a new one, one addition is putting the plea into the context of reparations.

“It ties in as a form of reparations because we are dying out here,” Ealom says. “We’re begging for clean air as a reparation at this point. As well as quality living, housing, education and employment. The basic needs that people right on the other side of the City don’t have to worry about.”

“We just feel abandoned out here in no man’s land.”

Arieann Harrison, Founder of Marie Harrison Community Foundation Inc., emphasizes that capping the contamination won’t protect the new residents of Lennar’s new condominiums if sea levels rise as projected.

“Sea level rise is real and prevalent for us in all shoreline communities,” Harrison says. “We’re in earthquake country, too. If we don’t address this now, we’ll be one natural disaster from the situation being completely out-of-hand.”

“I don’t want to see the next generation have the same health issues that we’ve had.”

Harrison is continuing her mother’s fight for the Bayview, an important history of activism that goes back to the Bayview’s “Big Five” Black women protesters of the 1960s. The question on her purple T-shirt, which is also the title of her newly formed non-profit, is one she’d like the rest of San Francisco to consider during Black History month, and beyond: “Can we live?”

Part of that question requires acknowledging that Bayview has been at best neglected, if not abandoned, since the shipyard closed. From adequate healthcare to education and transportation, the southeastern part of the city has mostly been treated as the place to treat waste. The community feels treated likewise, which Harrison illustrates through the recent settlement that awarded millions to those who bought certain Lennar properties.

“What a slap in the face to us long-term residents, that people who just came here and bought property can get a financial resolution for their property value going down because they found out they were on toxic land.”

“When it comes to our community ills, people love to holler, well, money doesn’t fix everything,” Harrison says, then chuckles at the irony. “But it only doesn’t fix everything when it comes to us, right?”

The protestors start their march south down Third Street, passing Bayview institutions drenched in rich history, such as Sam Jordan’s Bar and Grill (closed in 2019) and Auntie April’s Chicken Waffles and Soul Food. The group stops at Newcomb and Third in front of public housing and just down the street from the iconic Bayview Opera House, the oldest theatre in San Francisco.

Dr. Ahimsa Sumchai held up a map to point out what’s next to all of this rich culture and history. “Everything from Evans, where we started our march, to the southern end of the slough, is within 6-7 blocks of a system of federal superfund sites.”

Sumchai, a Stanford trained physician whose father was a long shoreman at the shipyards and died of pulmonary asbestosis, runs a biomonitoring clinic that checks for contaminants in patients that can be linked to the superfund sites. She introduced her “guardian angel” in the fight, Dr. James Dahlgren, who was an expert witness in the famed Erin Brockovich case against PG&E.

“Let me just say this. We know there is a cancer cluster in this neighborhood,” Dahlgren said. “It’s iron-clad. We don’t need another study.”

Dahlgren noted that a 1995 study by the City’s Health Department proved this.

“The Department of Health documented an increase in breast cancer in this zip code that was twice as high as the national rate. What did they do about it? They stopped measuring. They stopped measuring the cancer rate in the neighborhood.”

Another moment when the people of the Bayview felt abandoned. As the protest wound up, community members milled around, exchanging hugs before heading back to their homes. Amid the appreciation of a spirited march lingered the worry Bayview has carried for generations: being forgotten yet again.