While Joan Brown is frequently associated with the second generation Bay Area Figurative Movement, like Manuel Neri (with whom she studied, collaborated, and was at one point married), it is difficult to place her within a single art historical movement. Curated by Janet Bishop and Nancy Lim, the retrospective “Joan Brown” at SFMOMA (through March 12) showcases the evolution of the artist’s work with particular emphasis on her unique vision after 1960. As the exhibition reveals Brown’s exploration of self-portraiture and masquerade, it suggests the artist as a shapeshifter, where formal innovations are mirrored in her expanding narratives and identities.

The exhibition is arranged chronologically, with the first gallery featuring works like “Girl Standing (Girl with Red Nose)” (1962) that firmly places Brown’s early work within the Bay Area Figurative Movement, influenced by Elmer Bischoff, her mentor at California School of Fine Arts (later named San Francisco Art Institute.) Like Bischoff’s work, Brown’s thick impasto brush strokes in a muted color palette portrays a single female figure placed in an ambiguous background.

The second gallery highlights how Brown developed her individual voice through the introduction of personal narrative. In “Noel in the Kitchen” (1964) Brown explicitly begins to reference specific individuals, in this case her son and dog, within the context of her intimate domestic space. Markedly, this work’s background becomes more representational and dimensional, with its kitchen cupboards bulging with thick mounds of paint. While the evenness of Brown’s treatment of the figure and ground in her earlier painting “Girl Standing” created a more vague sense of place, here the background becomes more important and establishes elements of her identity as mother.

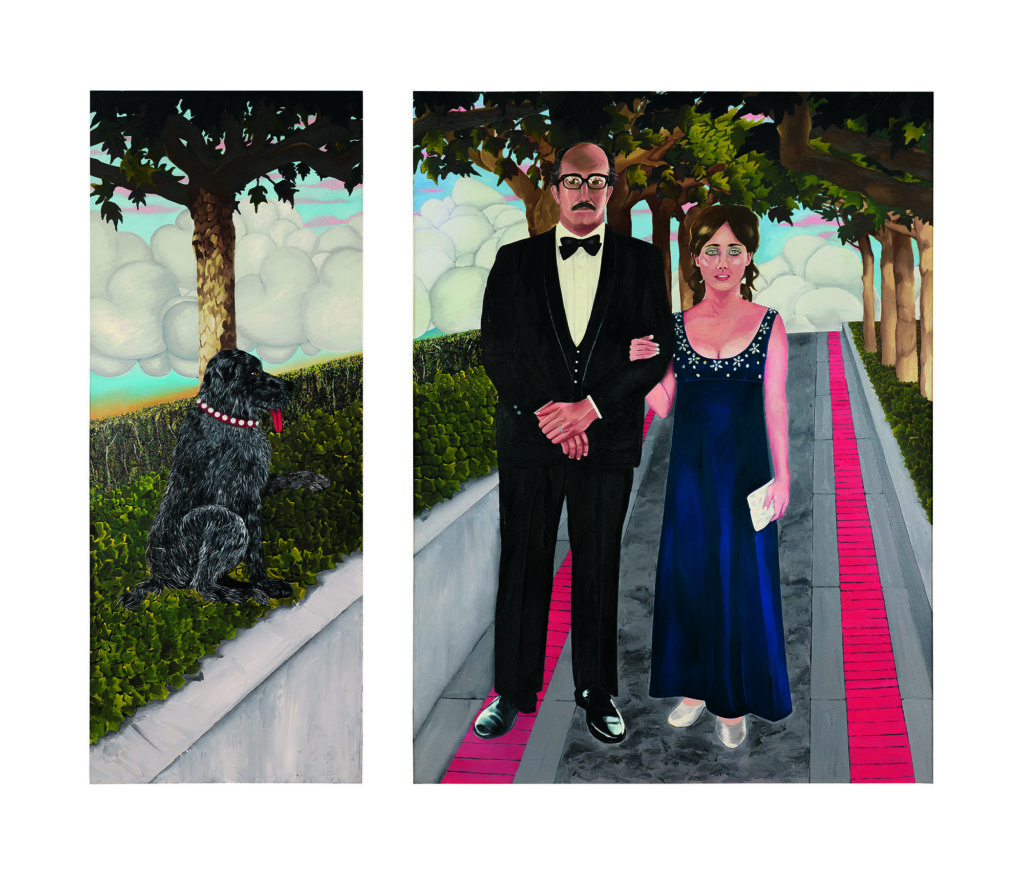

Most excitingly, the exhibition highlights a decisive formal and narrative progression in Brown’s work in the late 1960s. Influenced by the Surrealist artist Henri Rousseau, Brown replaces her impasto brush marks with more graphic shapes, flatter surfaces, higher saturated color, and surrealist imagery. In “The Bride” (1970), Brown paints a woman with a cat face in a white wedding dress politely holding a bridal bouquet. It’s unclear if this is a mask that conceals the woman’s face, like in “Woman Wearing Mask” (1972) or a feminine feline hybrid. Contextualizing Brown’s surreal figure, large fish float in the turquoise background while a giant hairy rat sits at the bottom of the picture plane and in the foreground. While not explicitly identified as a self portrait, “The Bride” strongly resonates with her recent marriage to Gordon Cook, commemorated in “Gordon, Joan + Rufus in Front of S.F. Opera House” (1969).

As Brown continued exploring her merged personae of artist, mother, wife, and cat, she also explored dualities of light and dark, life and death. In “Harmony” (1982), Brown represents herself as a bifurcated individual, half artist and half cat. Distinctly composed of two panels, Brown appears on the left side in blue paint-covered studio cloths against a sun lit yellow background. In contrast, on the right side an anthropomorphized yellow cat stands against a blue background with a moon. In “Harmony,” Brown embraces her shapeshifting identifications, where the daily artist’s life merges with the imaginative world of the mystical night.

As Brown has moved from the painterly materiality of Bay Area Figurative painting to more surreal and autobiographical content, the retrospective positions Brown as an ever-exploring and inventive artist. It provokes questions of how we categorize the artist’s career. As a woman artist, mother, and wife, Brown’s prescient understanding of the fluidity of identity and masquerade produces a complex and distinctive body of work that defies simple classification.

JOAN BROWN runs through March 12. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. More info and tickets here.