Sex work is big and—unfortunately, yet again—controversial news in San Francisco at the moment, as the city fruitlessly attempts to shut down Capp Street’s thriving trade with actual concrete barriers. (What if we had leaders who fought for legalization instead of incarceration?) But sex work in San Francisco has a long and storied history in the city, especially among marginally housed young queer men in the Tenderloin and on Polk Street, many of whom have been rejected by their parents and make their way to the city to find a new life. Of course, not all turned to hustling, but a longstanding community of marginalized LGBTQ people lean on each other for survival, forming unique bonds that existed at the edge of anti-gay, anti-poor, anti-sex worker laws.

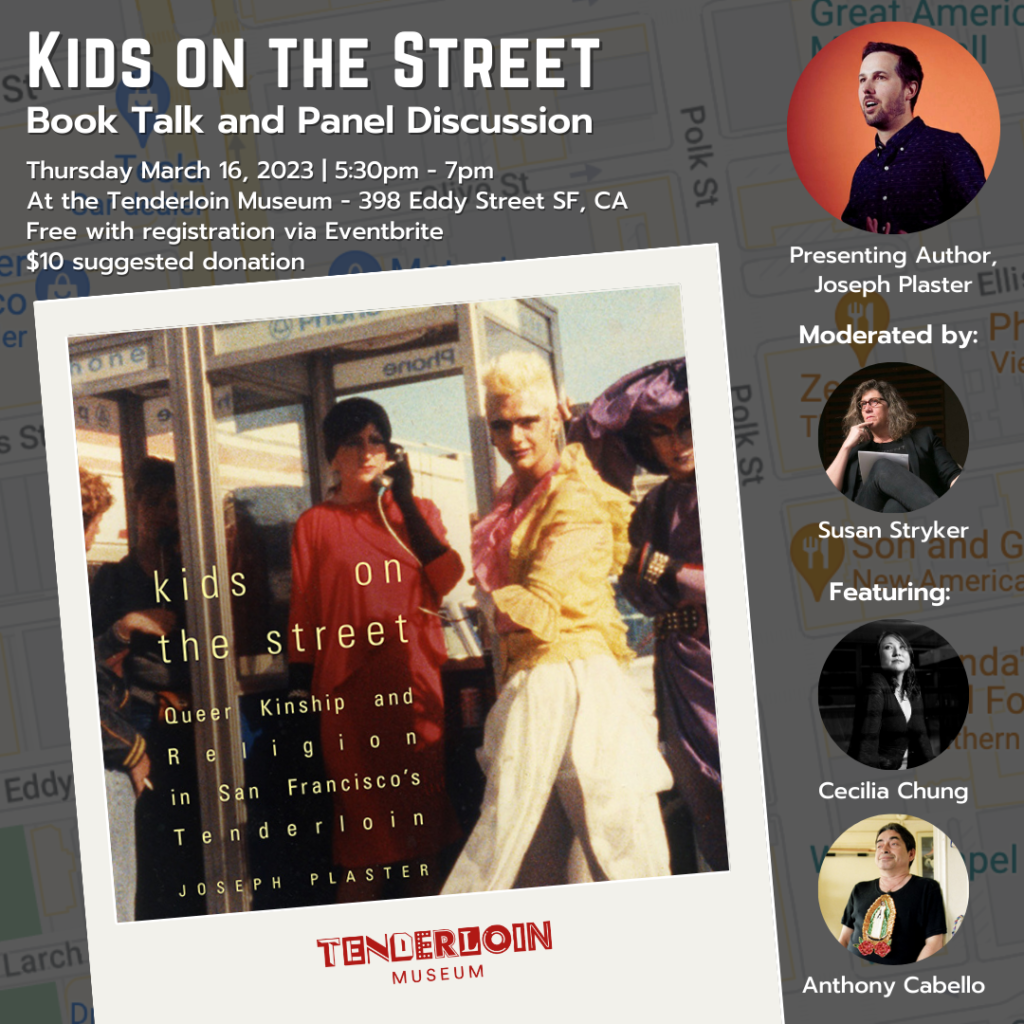

Joseph Plaster‘s academic but highly accessible new book, Kids on the Street: Queer Kinship and Religion in San Francisco’s Tenderloin (Duke University Press) ranges from the 1950s to the present to “outline the queer kinship networks, religious practices, performative storytelling, and migratory patterns that allowed these kids to foster support and mutual aid.” (Plaster will be speaking Thu/16 at 5:30pm at the Tenderloin Museum, more info here.) It doesn’t shy away from the more brutal and exploitative risks of this life, one mostly foisted on young people by a conservative society that shuns them. But it does show the remarkable resilience of poor and housing-unstable queer family—a “moral economy of reciprocity” as the book puts it—that has held strong in the San Francisco Tenderloin and other “tenderloin” zones throughout the country, and which has “been overshadowed by major narratives of gay progress and pride.

Along the way, and through dozens of fascinating interviews, we get colorful histories of organizations like Vanguard, the homophile group from the 1960s that helped organize and support those who worked the “meat rack”; descriptions of the scene around the Compton’s Cafeteria riot and other historic moments of resistance; and indelible characters like Reverend River Sims, the “punk priest of Polk Street” who helped introduce Plaster—now a Yale PhD in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies—to the hustling culture of the Tenderloin in 2007. Names of long-gone places like the N’Touch, Reflections, and the Giraffe may spark some nostalgia for the area, once a thriving center of queer San Francisco life.

I spoke with Plaster over the phone before his coming talk and panel discussion.

48 HILLS I know this book has had a long gestation, from way back in the 2000s when you were a Bay Guardian intern! Tell me a little about how you became involved with the subject?

JOSEPH PLASTER I’m a little fuzzy on dates, but I know it all began between when I graduated Oberlin in 2001 and was at the Bay Guardian in 2007, when I made my way to San Francisco. The first thing I did was walk around the city to get some idea of what it would be like to live here as a queer person. I walked around the Castro, which didn’t call to me, and then SoMa with the leather bars and the Stud, which I loved. And then I went down to Polk Street and the Tenderloin, and it just felt like the area that did call to me. I knew it was romanticized as a place of outsider queer culture, and it fit right into where I was at the time, rejecting the norms of growing up in a conservative family in Florida. I loved dancing in the bars, and hanging out with the people there, the feeling of it.

This was after the first dot-com boom and bust, when social media coming up and there was this wide-scale gentrification of the city, a hyper-gentrification. Neighborhood associations, business owners, and the police were trying to “clean up” the area and basically demolishing the queer culture that had been there for decades. All the bars and clubs were closing, and the people left there were being further marginalized and criminalized. I wanted to document that history that was in danger of being erased, but in an ethical, engaged way that didn’t feel like it was exploiting the community.

48 HILLS I love that you waked around San Francisco to find out about queer life, it seems so quaint and romantic in the Age of Apps. I also completely remember that period of “de-Polkification”—like business groups “rebranding” the legendary Polk Gulch area as “Polk Village.” How did you approach the documentation of it all?

JOSEPH PLASTER It was really essential that the community be engaged in telling the story through the people who lived it. I conducted about 70 oral histories, some of which I made available along the way as audio portraits and listening projects. There were major contemporary themes like the criminalization of homelessness with the Sit/Lie Law and the closure of the queer clubs, which was a phenomenon happening in queer neighborhoods around the country at that time, mostly due to real estate and rental prices.

Gentrifiers were coming in and saying that Polk Street was unsafe for families. But who were they really trying to make the area safe for? Who were they putting in danger? The queer kinship networks and family that had formed over decades—what about their future in the neighborhood? That helped me focus and start pulling the book together.

It took me a while to figure out what this book was actually about, but as I researched in archives like at the GLBT Historical Society and panned out to look at other downtown “vice districts,” what emerged was that queer street kids from as far back as the 1920s formed this politics of mutual aid and reciprocity. “I’ll watch your back and you watch mine” was necessary for mutual survival.

The other part was that street kids found ways to embody and instantiate these politics though performance, with kinship terms like drag mother or daddy or uncle [for patrons and Johns], or religious ritual in the context of street churches and other performative acts.

48 HILLS What was a particularly colorful interview that comes to your mind?

JOSEPH PLASTER I immediately think about Alexis Miranda, a drag performer, bartender, and former Empress of the Imperial Court. I would go day after day into Divas bar, order drinks, and chat with her. She would sometimes lecture me about newspaper reporters coming in and writing sensationalist stories about the drag and transgender scene. [laughs] You really felt the impact of queer family in her stories. She talked about her drag mothers who mentored her way back when, and taught her to embellish rhinestones on her clothes and make money as a female impersonator. She spoke so fondly of all of the drag daughters she was mentoring. She was even living with her drag grandmother at the time. Divas was such an important space for kinship, and now it too is gone.

Another fascinating interview was Coy Ellison. I met him through Sweet Lips [longtime nightlife columnist for the Bay Area Reporter]: Coy became Sweet Lips’ caretaker through the end of his life. He started telling me his own story of coming to San Francisco in the ’70s. When he arrived, he passed himself off on the streets as an illegal Irish immigrant, and he used that persona for at least a decade. It was a fabrication, but he used that story to reinterpret and reevaluate the abuse at home that he was running from. It’s a really powerful example of how he was able to transform himself through re-invention, and become the kind of queer person he wanted to be. When Coy told me that story he said that his life was basically Emperor Norton syndrome—you tell a story and people play along until it becomes true.

People in the Tenderloin are the most powerful and creative storytellers. Storytelling is a survival strategy, it creates kinship and transforms their circumstances.

48 HILLS I think most readers will be surprised to see the word “religion” in the subtitle of the book, especially considering that organized religion was one of the major things these kids were running from. Yet Vanguard was formed in the basement of Glide Church by Protestant reformers who wanted to help street kids, and there are so many other examples throughout the book of how religion and queer kinship intersect… including the veneration of Stonewall uprising veteran Sylvia Rivera as a saint.

JOEY PLASTER That’s the things that surprised me most in my research, I saw religion and Catholicism everywhere I looked. Catholicism was a common frame through which acts of reciprocity could be viewed, along with the elaborate rituals and ceremonies that were performed on the street and between people. There were street churches, headed by ordained queer ministers, that helped guide newcomers and sustain people who lived very hard lives.

Sex workers and street kids themselves lived their lives outside the bounds of middle class sensibilities, and in fact denouced the “respectable” world as immoral—that, in a way, elevated them from feeling society’s judgement. They created their own moral framework, their way of reinterpreting the world. This culture has been incredibly creative and surprising in the ways it has sustained itself.

KIDS ON THE STREET: BOOK PANEL AND DISCUSSION Thu/16, 5:30pm-7pm, free with RSVP; $10 suggested donation. tenderloin Museum, SF. More info here.