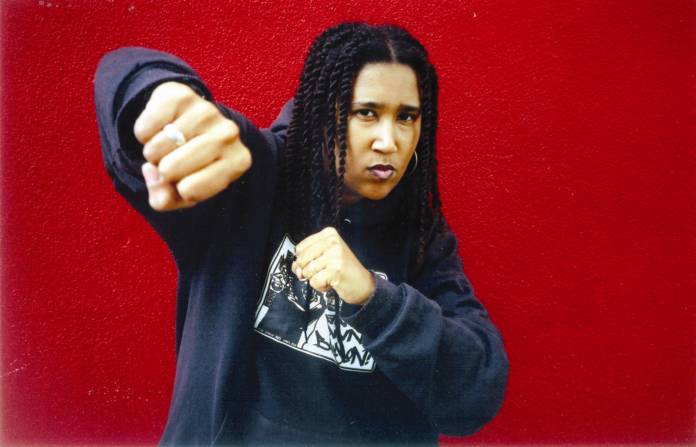

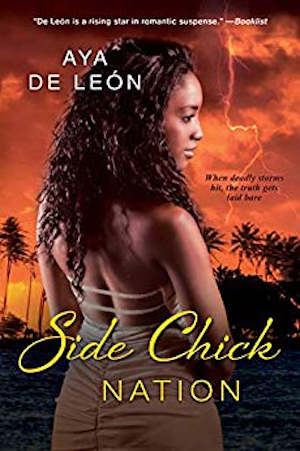

LIT Aya De León is a writer, activist, educator, spoken word poet and author of the award-winning Justice Hustlers series, including latest installment Side Chick Nation. The Director of June Jordan’s Poetry for the People, she teaches poetry and spoken word at UC Berkeley and is an alumna of Cave Canem, VONA and Harvard University. We caught up with her before her reading at Octopus Literary Salon, Tue/20.

48 HILLS Tell us about the Justice Hustlers series of books. You describe it as “feminist heist/romance.” What do you mean?

Aya De León: As far as feminist heist, this is a Robin Hood series about a group of women who are redistributing wealth from representatives of the patriarchy to low income women of color. Sometimes they use the funds in direct reparations to specific groups of women who have been harmed. Sometimes they fund institutions that meet the needs of those communities. But I see these women engaging in direct action on behalf of their communities.

As far as feminist romance, the book would fit into the category of romantic suspense. The story follows the woman, as her choices generate the central action plot. As a secondary plot, the series uses the traditional tropes of romance to plot the trajectory of a heterosexual couple where the man really loves her, but the relationship reaches a crisis where the man needs to choose between his allegiance to patriarchy and the woman he loves. Because these are happily-ever-after romances, the man is tested and initially falters, but in the end he always chooses the woman.

48H Your latest novel, “Side Chick Nation” is set in post Hurricane Maria Puerto Rico. What do you hope the reader will learn about the island?

ADL By creating a point of view character who goes through the hurricane, I wanted audiences to have a deeper level of empathy with the people of Puerto Rico and what they experienced, both in terms of the hurricane and the ongoing storm of colonization by the US. My protagonist, Dulce, is an outsider to PR, so her POV seemed a little too removed to carry the story alone.

The secondary protagonist, Marisol Rivera, is Puerto Rican. In later drafts, I added the POV of her cousins. Dulce could show us the trauma of the storm itself, but couldn’t show the devastation to a character’s home and homeland. I wanted to make sure that was part of the book, as well.

48H As a politically engaged author, do you find that fiction can do things that non-fiction can’t?

ADL Empathy is at the core of my politics. If I only write non-fiction, I can only create narratives where people empathize with my limited personal experience. But through fiction, I can create characters who live all kinds of different lives, and create empathy for their lives among my readers.

The danger of course is that I haven’t lived those lives, and I am vulnerable to writing cliche or stereotype about identities that I don’t share. Which is why I used sensitivity readers, even when writing about communities where I do have a lot of familiarity. I find there is always something that can be changed to better reflect not only the reality of those communities, but the movements that those communities have organized for their freedom and survival.

48H You are one of the Bay Area’s best known poets. How has the poetry scene changed here in the past few years now that the Slam scene is not as large as it used to be?

ADL: Sadly, as a working mom who has been writing a book a year for the last five years, I don’t get out that much. When I was in slam, in the early 2000s, it was HUGE. The Bay Area had the biggest slam in the nation. But artistic movements change. Venues close. Artists and producers shift their focus.

I see an incredible amount of energy continuing in the youth slam scene, Youth Speaks and Brave New Voices continue to have a lot of momentum. We’re also seeing lots of writers from slam communities come of age and branch out into longer forms.

Within the last decade, I also watched some of the slam and poetry momentum shift into storytelling: The Moth, Snap Judgment, and other storytelling slam spaces have gotten really large audiences and have been spaces of really good composition, even if the writing is more conversational, and isn’t always as dazzling at the sentence level, as is the case with poetry. But the storytelling form is that these need to be true stories. So there’s a different power. This is sort of the opposite of what I had said about the power of fiction. Fiction has the range. But non-fiction has the power of personal testimony.

Aya De León reads from Sidechick Nation Tue/20, 6:30 at the Octopus Literary Salon, 2101 Webster Street, Oakland.