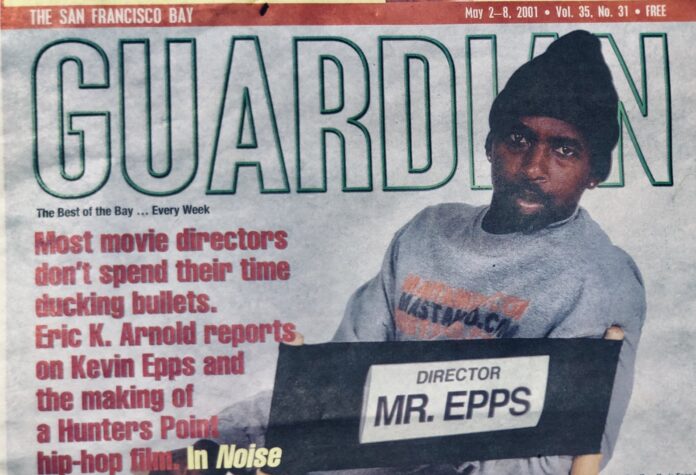

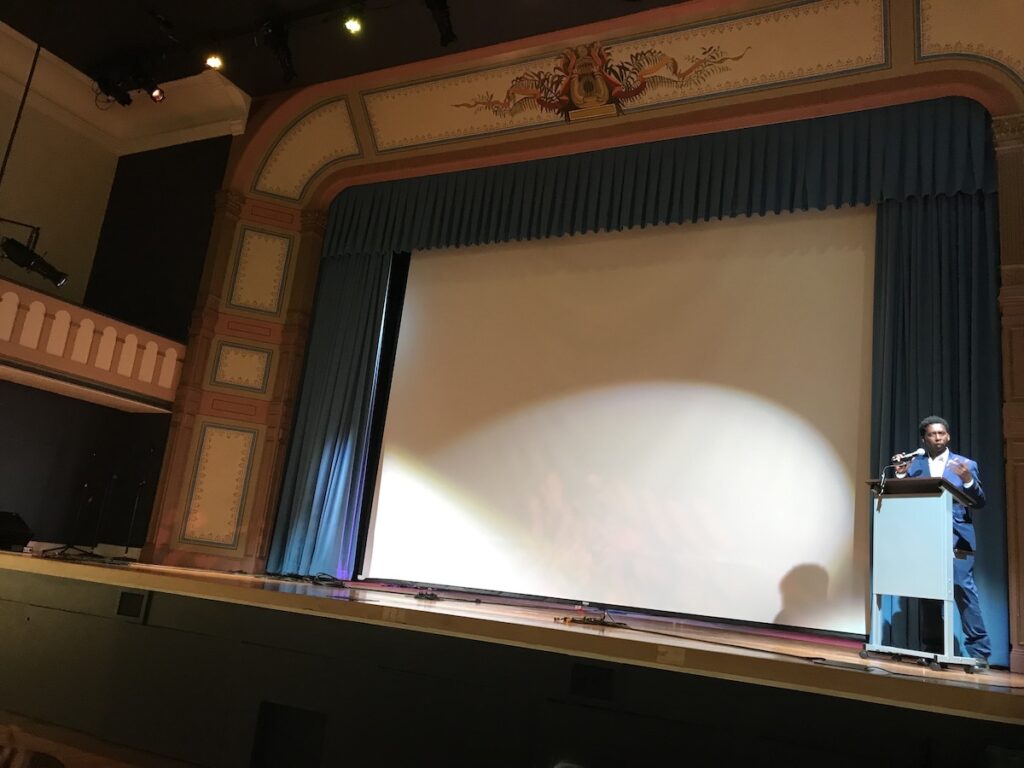

On the steps of the Ruth Williams Memorial Theatre off Third and Newcomb this past Juneteenth, Bayview Opera House Program Manager Ashley Smiley and Straight Outta Hunters Point film director Kevin Epps prepare for the night’s big event, a 20th anniversary celebration of his landmark film.

“There’s no more important place in the world to show my film than the Bayview Opera House,” Epps said, looking sharp in a blue suit and white shirt. “Home. Bayview. Means a lot to me.”

In terms of what has changed over the past twenty years, Epps highlights the resiliency of the Black community in the Bayview.

“We’re still here. We might have had some teeth pulled out, but those roots are still there, you know? Everyone is twenty years older but still here. That’s the resilience that makes the Bayview.”

Considering all that the Bayview has had to endure, both agree that the resiliency of the community is the greatest testament, a resiliency that can be traced back to 1944 when The Reporter’s Thomas Fleming’s answered San Francisco Mayor Lapham’s question of “How long do you think these colored people will be in San Francisco?”

“Mr. Mayor,” Fleming responded, “Do you know the Golden Gate? It’s permanent. Well, the Black people here are just as permanent.”

Audience members start arriving outside the theatre, dressed to the nines, like a throwback to the Fillmore “Harlem of the West” days. Sincere hugs multiply easily as the crowd grows in the glorious if surprising San Francisco summer sun.

“I lace my kids up every day about community,” Epps says. “And Juneteenth brings everyone back to the Bayview who were forced out to the suburbs like Antioch and Vallejo.”

Help us save local journalism!

Every tax-deductible donation helps us grow to cover the issues that mean the most to our community. Become a 48 Hills Hero and support the only daily progressive news source in the Bay Area.

Smiley remembers seeing the film when she was in middle school and living on Quesada Street in the Bayview. “I remember being much younger and watching Straight Outta and thinking, wow, this is the most honest thing. It’s what San Francisco won’t talk about, but it’s so alive.”

With the Black population hovering around 5%, Smiley believes Juneteenth is a good day to remind San Franciscans that “Black people—and Black artists—are in and of San Francisco.” She notes that the artwork inside the Opera House is by eight local Black visual artists.

As far as how the day’s trifecta—Juneteenth, 20th anniversary of Straight Outta and Father’s Day—speak to each other, Epps becomes emotional, pointing to his young son and daughter playing on the Opera House staircase.

“Took those two to church today. I didn’t have a father, so those things mean a lot to me. That anchors my life.”

“It’s been a struggle for many Black men to represent like this. In the context of Juneteenth, there’s always a struggle because there’s always misinformation about who we actually are as a people. That builds itself into a body of work that’s a lie.”

As a documentary film maker, Epps is acutely aware of how important these stories are. If the story is a lie, that lie can be repeated and amplified by those who wish to take advantage of that lie. For people of color, the cumulative damage of these falsehoods lead to social, economic and environmental injustice.

That’s why Straight Outta Hunters Point, made by a Bayview resident for Bayview residents, is a hard but honest truth for Epps, Smiley and many in the crowd waiting inside.

“It’s deep. It will make you laugh, make you cry. But there’s hope in there.”

***

The festivities inside the Opera House kick off with a roar from Pat Wilder, the legendary Bay Area R&B guitarist whose first guitar came straight from Taj Mahal himself. She sets the tone of the evening with a joyous mix of original songs like “Follow Me” (“for the youth in the Bayview who can sometimes get lost”) and classics like her rousing finale of “I’ll Take You There” that had the crowd on their feet shouting back the chorus.

San Francisco Poet Laureate Tongo Eisen-Martin takes the stage alone but commands it no less. As emcee Smiley puts it, “If you haven’t heard Tongo’s poetry yet, what have you been doing with your life?”

Over 20 mesmerizing minutes, poetry ruptures out of Martin, who stands stock-still, transfixed, swaying only slightly as if channeling the historical pain of his people straight out of the land itself.

Our perfect confidence in the sun

In commemoration

every tambourine a thousand miles in every direction

playing in a California rent party

rattlers dancing and bleeding over God’s non-whitened skin

After Eisen-Martin leaves the stage, Epps, knowing his film is better experienced than explained, tells the back of the house to “press play.” The curtain pulls back, and Straight Outta Hunters Point explodes onto the screen.

Why Smiley described the film as an “honest thing” that’s “so alive” makes sense from the start. Epps films with a hand-held camera outdoor but in intimate spaces, from the low-rider, slung-back front seats of drug dealers to the crammed apartments converted into sound studios of several of those same dealers practicing their rapping skills as the best hope for a better life. (RBL Posse is one of the more famous examples.)

The narrative is book-ended by the life and death of Bumper Joe, a well-known Bayview Hunters Point resident whose infectious energy fills the screen but who ends up in a coffin.

In between these day-to-day struggles, Epps weaves the larger backstory of the Bayview, from the boom in the Black population pre-WWII, to the socio-economic battles led by community leaders like Bay View newspaper owners Willie and Mary Ratcliff and Dr. Ahimsa Sumchai. (They still fight for the health and dignity of Bayview residents to this day, joined in the fight by other activists in attendance, including Arieann Harrison, daughter of Marie Harrison and founder of Can We Live?)

The film ends with a postscript that “the struggle continues,” and that prompts an animated audience Q&A with Epps. Bayview audience members seem clear-eyed about the economic realities of San Francisco, the fact that boom and bust cycles since the Gold Rush have pushed people out as they draw others in.

But they also know there’s a value to the music, poetry, and film they just witnessed, art that would never have existed if they had not persisted in San Francisco.

On that note, a comment from an audience member alerts those who might change the Bayview without thinking twice to, well, at least think once.

“If you’re not from here but only work here, you don’t really know here.”

One last round of applause after nearly four hours that flew by, and the crowd spills back into the night, a clutch of hugs and goodbyes in their Sunday bests. The celebration ends but, like Juneteenth itself, the Bayview hopes San Francisco will remember its southeastern family for more than just one day.