The most interesting bit of data in the new report on homelessness in San Francisco is one that is hardly a surprise—but isn’t at the top of most news media reports.

Here’s that statistic: For every person or household that the city moves into housing, four more become homeless. And 71 percent of them were living, housed, in San Francisco before they became homeless.

Let’s look at the data, which you can find here.

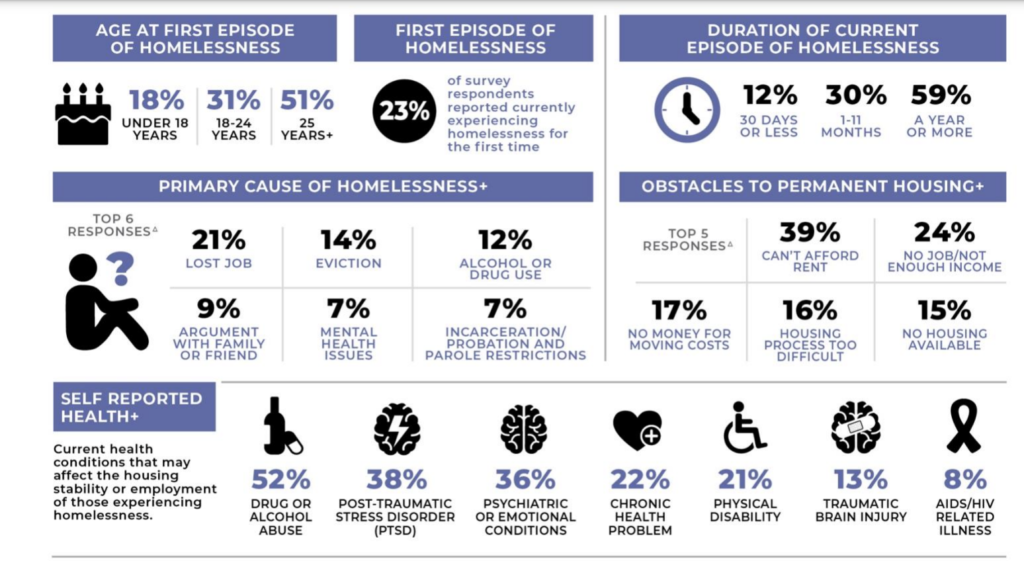

Of the top six reasons people gave for losing their homes, 35 percent (by far the largest number) cited job loss or eviction. That is: They can’t pay the rent. Only 19 percent cited alcohol, drug, or mental-health issues as their primary reason.

Then, under Obstacles to Permanent Housing, the data is even more clear: Some 80 percent of homeless people said they can’t afford to pay for housing, or can’t afford moving expenses.

Do we need any more data to make this clear?

The homelessness crisis is not, primary, a crisis of people who drink, do drugs, and have mental health issues, although these are important problems and need to be addressed. (I think it’s safe to say that many people who become homeless because they got evicted then develop substance-abuse or mental-health issues.)

The real problem is that landlords are charging too much for rent, the city hasn’t been able to prevent that, and we don’t have enough affordable housing.

There is absolutely no way in any imaginable universe that clearing obstacles to private developers building market-rate housing is going to have the slightest impact on this problem.

And the price tag for building the affordable housing that even the state regulators say the city needs is $19 billion—and nobody in the Mayor’s Office has any clue where that will come from or plan to fund it.

The community hit hardest by homelessness in this year’s study is the Latinx community, which has been hit hard by job losses during Covid. Let me make this as clear as I can: If you are currently housed in San Francisco, and you lose your job because of Covid or anything else that isn’t your fault, you should not become homeless.

There are so many ways the city can prevent this, all of them much cheaper than to cost of addressing a growing homeless population. It’s way cheaper for the city to pay someone’s rent than to take care of them when they wind up on the streets.

It’s way cheaper to limit Airbnb rentals, to impose rent controls on vacant apartments, to eliminate the Ellis Act, and to make sure that everyone facing eviction knows that they have the right to counsel than it is to “solve” homelessness.

Some of that is the fault of the state Legislature. At a demonstration against an Ellis Act eviction recently, Sup. Rafael Mandelman said that someone in Sacramento needs to make the repeal of that law their primary objective. State Sen. Scott Wiener has proposed lots of bills that make landlords and developers happy; he has never once said that his pro-developer housing agenda must at all costs include Ellis repeal.

Assemblymember Phil Ting, who chairs the Budget Committee, hasn’t said that all appropriations that could help landlords or developers are on hold until the Ellis Act is repealed. I haven’t even heard new Assemblymember Matt Haney mention it.

So the city, thanks to weak representation, is missing some of the tools it needs to protect people from homelessness.

But there is so much that we can still do. If 20,000 people experience homelessness at some point in San Francisco, and 71 percent of them had a home in San Francisco, that’s 14,000 people who the city could have kept in their homes.

The Mayor’s Office has done, as far as I can tell, next to nothing to make that a priority.

I’m still waiting to hear which taxes Mayor Breed will raise on which rich people and big business to cover that $19 billion.

That’s the housing discussion we need to be having.