The Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive is hosting the first major retrospective of the works of 79-year-old Chicana feminist artist Amalia Mesa-Baines. Called “Archeology of Memory,” it runs through July 23. (Read Emily Wilson’s interview with Mesa-Baines and the curators of the show here.)

Mesa-Baines was part of an important movement of artists who began bringing the cultural-religious practice of the Mexican altar—la ofrenda—into the realm of Californian art practice and art object. Beginning in 1975, Mesa-Baines began making ofrendas from found materials, debuting this work in San Francisco at the Mission District’s Galería de la Raza. The gallery became an epicenter of West Coast United States altar work when it began hosting Día de los Muertos community celebrations in the early ’70s.

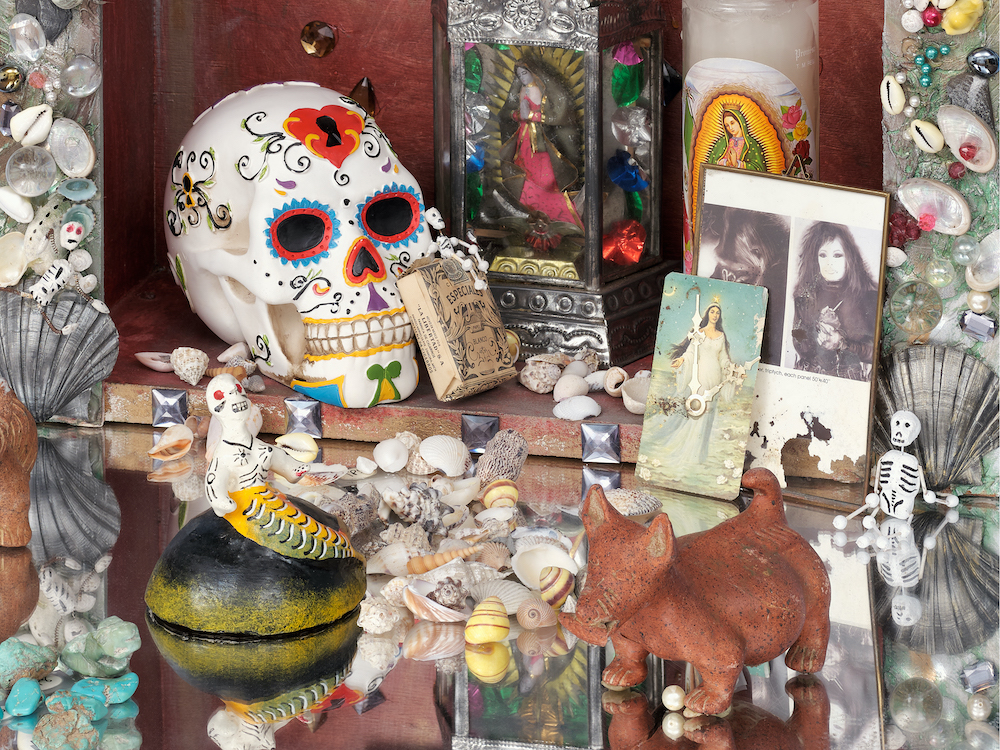

Photographs, beads, costume jewelry, rosaries, postcards, fabric, tools and instruments all feature in Mesa-Bain’s installations. These individual objects are disassembled and re-assembled to form new pieces—constantly evolving, ephemeral versions of her work. At any one time, Mesa-Baines has several suitcases of items on hand for this purpose. In the past, she has joked that she would never be able to hold a retrospective of her work because she reuses so many of her materials. And yet, and after 50 years of activity, just such a retrospective is here.

Born in Santa Clara, Mesa-Baines is the child of parents who crossed the Mexico-US border as children in the 1910s, who worked as a maid and farmworker, and remained undocumented workers until the end of their lives. Mesa-Baines met her husband, Richard Bains (now the chair of the Music Department at CSU Monterey) in the Summer of Love in 1967—the same year she held her first art show at the Palace of Fine Arts. For 20 years, Mesa-Baines worked as a multicultural psychologist and taught English as a Second Language (ESL) at San Francisco public schools.

She has published two books, Homegrown: Engaged Cultural Criticism, co-written with bell hooks in 2006, and this year’s Archaeology of Memory, featuring an essay on Chicana art which accompanies this retrospective of her work at BAMPFA.

Colorful, multi-dimensional, and evocative, Amalia Mesa-Baines works sometimes evoke the act of stepping into the private bedroom of a house that has been lost to time. Her carefully selected objects interact with one another. In one piece, a ring of chairs appears to be in conversation. She creates a destination with her works, some of which announce arrival not only visually but through other senses, as in her installations ringed with dried flowers.

Mesa-Baines work shares qualities with a number of other multi-media artists that pushed the boundaries of feminist and ethnic art. She shares a background of multicultural education and art practice with San Francisco artist Carlos Villa (whose own first retrospective occurred last year), and similarities between the two artists can be seen in their work that utilizes indigenous materials. Mesa-Bain’s furniture installations and curio cabinets create the intimacy and interiority of closed rooms, evocative of Louis Bourgeois’ “cells.” “Cihuatlampa with Mirror” from the “Venus Envy” series calls to mind the larger-than-life women depicted by French feminist artist Nikki De Saint Phalle.

The influence of Mexican painter Frida Kahlo is also present in more ways than one.

Help us save local journalism!

Every tax-deductible donation helps us grow to cover the issues that mean the most to our community. Become a 48 Hills Hero and support the only daily progressive news source in the Bay Area.

Like Kahlo, Mesa-Baines also experienced a life-threatening car accident, followed by a long and introspective period of recovery. She opted against surgery and instead embarked upon a 20-year exploration of traditional medicine, curanderismo, and “bringing the soul back to the body” through art.

In a 2018 interview in ARTnews, Mesa-Baines said, “Princely [collections] were often organized according to random or fabricated categories of meaning. In seeking to know the world at large, collectors frequently developed systems of taxonomy based on partial knowledge and preconceived notions.” She said she sought to “restore spiritual meaning” to the objects she uses as materials in her art, drawing parallels to a theoretical de-colonial process by which indigenous objects removed from their places of origin by colonial “inquiry” might be restored.

Mesa-Baines rarely sells her artwork; she views the materials that compose her assemblages as belonging to her mother, father, and grandparents. Of all her installations, she has sold only three in her career.

In the 1980s, Chicano scholar Tomás Ybarra-Frausto coined the term rasquachismo (from the Nahuatl word later adopted by the Spanish, rasquache, meaning “poor, coarse, or vulgar”) loosely defining the concept as “the view from the underdog” or “the view from below.” More broadly, it describes a working-class attitude that can be extended into an art practice, an inventiveness that arises from working with limited materials, and a DIY ethic that was once found all over, largely in art cars and at punk shows—but that now has all but disappeared from our streets.

Mesa-Baines extends this into her own concept that pertains to women’s art in which, among other things, objects and materials found within the home are elevated into art objects. In an essay titled “Domesticana: The Sensibility of Chicana Rasquache,” Mesa-Baines writes, “Critical to the strategy of domesticana is the quality of paradox. Purity and debasement, beauty and resistance, devotion and emancipation are aspects of the paradoxical that activate Chicana domesticana as feminist intervention.”

The retrospective exhibit does have a week point. Mesa-Baines’ digital giclée collage prints featuring quotes from Chicana theorist Gloria Anzaldúa, who is now regarded critically for drawing upon Jose Vasconcelos’ eugenicist text La Raza Cósmica that advocates for invisibilizing Blackness and Indigenous identities in Mexican culture, could stand to be reevaluated. Perhaps due to their medium less than their message, these prints register somewhat as filler within the context of the exhibition, and underwhelm in comparison to her high-impact installations.

Still, Mesa-Baines’ maximalist, folkloric installations are a welcome departure from a minimalist world.

AMALIA MESA-BAINS: ARCHAEOLOGY OF MEMORY runs through July 23. Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. More information here.