Mayor London Breed and Sup. Joel Engardio introduced with great fanfare in April legislation that would “streamline” the planning process for new housing.

By removing unnecessary barriers and rules for projects that already comply with existing zoning, we can get housing built faster,” Breed said in a press release. “If we want to create housing for working people and families in this City, we can’t just talk about wanting more housing – we have to take action to cut the rules and regulations to get more homes built.”

The Chron proclaimed that the bill would make the city’s Planning Commission meetings a lot shorter. (It would—by taking away a lot of the commission’s authority over development and giving that authority to planning staffers, who could make decisions with no public input.)

The measure will come before the Planning Commission June 15 then will go to the Board of Supes.

Most of the discussion has been focused on larger development projects that involved building housing on what had been commercial or industrial sites:

Had it been in place the legislation would have expedited approvals of projects such as 2055 Chestnut, a 49-unit apartment complex on the site of a Wells Fargo branch. The development was approved in 2022 after a two-year process. The legislation also would have meant that 67-69 Belcher, a former furniture warehouse set for 36 units, would have avoided a conditional use hearing; as would have 650 Divisadero, which is approved for 66 apartments.

(Just for the record, 69 Belcher wasn’t just a “former furniture warehouse,” it was a thriving artist studio community.)

But there’s another side to this that nobody has mentioned, and I think it’s critical: The bill would eliminate conditional-use hearings for the demolition of existing housing, and would pave the way for developers to tear down thousands of houses, many of them single-family homes in the Richmond and Sunset, to put up denser projects.

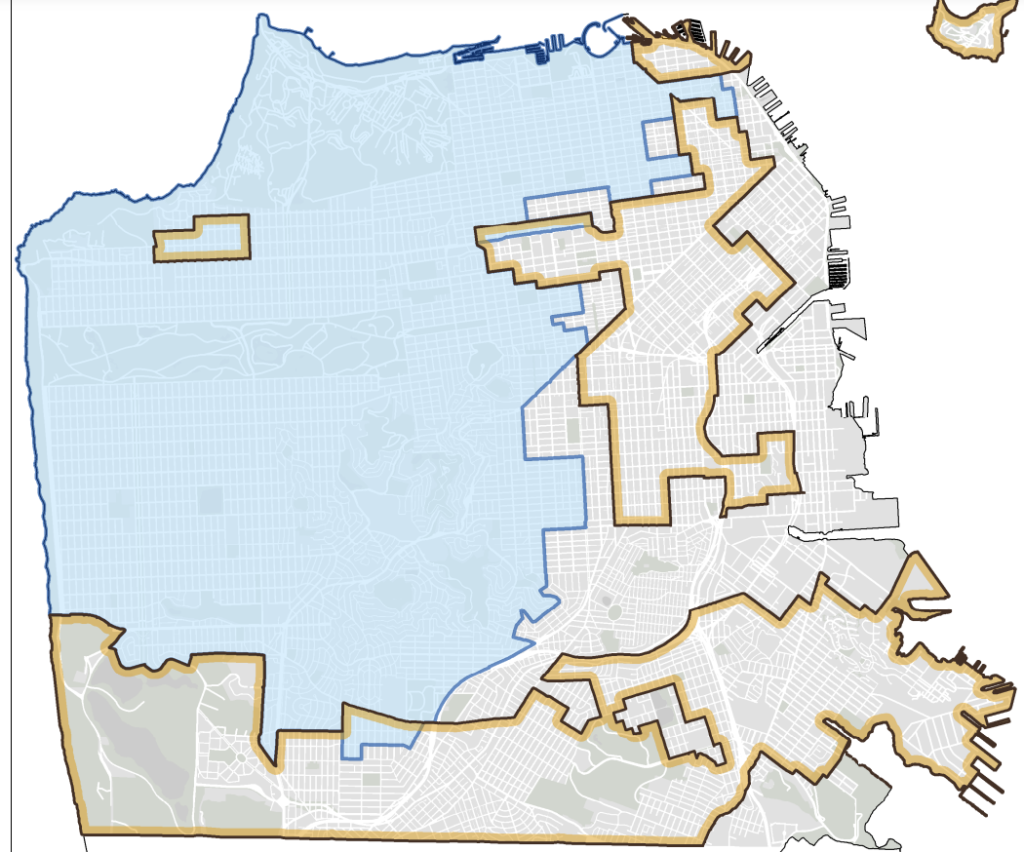

The legislation eliminates hearings for demolitions everywhere that isn’t a Priority Equity area, which means everywhere blue on this map:

Aaron Starr, legislative director for the Planning Commission, told me that the bill would allow what amounts to an over-the-counter demolition permit if

-The units to be demolished are not tenant occupied and are without a history of evictions under Administrative Code Sections 37.9(a)(8)-(12) or 37.9(a)(14)-(16) (aka No-Fault Evictions) within last 5 years.

– No more than two units that are required to be replaced per subsection (E) below would be removed or demolished.

– The building proposed for demolition is not an Historic Building as defined in Section 102;

– The proposed project is adding at least one more unit than would be demolished; and

– The project complies with the requirements of Section 66300(d) (aka SB 330, replacement relocation and first right-of-refusal) of the California Government Code, as may be amended from time to time, including but not limited to requirements to replace all protected units, and to offer existing occupants of any protected units that are lower income households relocation benefits and a right of first refusal for a comparable unit, as those terms are defined therein.

If you are located within the Priority Equity Geographies the existing rules apply, CU for any demolition of housing.

Engardio told me that

Significant landmarks, significant buildings, and contributory buildings listed under Article 10 and 11 (historic preservation codes) cannot be demolished.) … If there is something historic that needs protection and being overlooked, I’m happy to advocate for the necessary adjustments.

Here are the current landmarks and landmark districts under those planning codes.

As far as I can tell, none of them apply to anything on the west side of town.

Heather Knight apparently loves the plan, saying it would make the Sunset more like Paris. (She doesn’t note that in Paris, 100,000 new units of non-market social housing have been built since 2001, and 550,000 Parisians live in housing that is protected and never goes on the speculative market. That might be a great model for the Sunset. It’s not what city officials have in mind: The future of this housing will be entirely in the hands of profit-seeking developers, landlords, and speculators.)

Her lofty vision:

Think spots where seniors downsize, young couples buy starter homes and lower-income families afford a tiny corner of our pricey city.

There is no example, ever, in modern SF where this has happened through the free market.

In fact, according to Zillow, rents in this particular place where “lower-income families could afford a tiny corner” are currently about $4,200 a month for a two-bedroom apartment, and $5,200 a month for a two-bedroom with a den.

She gently approaches what the plan actually means:

Domicity involves slowly turning single-family homes — about 100,000 of which, he estimates, sit on cookie-cutter lots measuring 25 feet across and 120 feet deep — into small apartment buildings with a community space on the ground floor and five stories of housing above.

“Turning [100,000] single-family homes … into small apartment buildings” means massive, widespread demolitions of existing housing.

We saw this before in the 1980s, when the Residential Builders Association members demolished dozens of vintage Victorians in the inner Richmond to put up ugly, cheap, six-unit buildings. Rents in those units are not affordable today.

I don’t know how much we all care about the mass-produced post-War Sunset houses, which provided affordable home ownership to a couple of generations. Some of them maybe have some historic value. The Planning Department thinks some of them represent “extraordinary architecture by master builders.”

It’s not just the Sunset and Richmond; much of the Haight and the Castro are included in the area where demolitions can happen. District 8 Supervisor Rafael Mandelman asked me last year: “Do we really care about some buildings from the 1950s?”

I don’t know.

I’m not arguing that the west side of town should remain single-family homes; the city’s already changed those rules. There’s clearly room for more density in that part of town. Does that mean developers should be able to bulldoze 100,000 units, transform the west side of town, and make new and bigger buildings?

Whatever the answer, it’s a pretty big deal. And according to the current approach, there is no reason to believe the new housing will be cheaper than what is torn down. We are not talking social housing. We are talking market-rate development. (Oh, and by the way: Even in “Paris” the places that aren’t social housing, the lovely private, for-profit housing above the shops, is really, really expensive.)

The demolitions of existing housing will not lead to new affordable housing; that’s simple market logic. Developers don’t build unless they can make money, and if the new units won’t rent or sell for a hefty price, they won’t get built.

The law would, in theory, protect tenants from being evicted to make room for a demolition—except that landlords have been very, very good at finding ways around these laws. I think opening up big parts of the city for demolitions of existing housing by speculators and developers is going to lead to a lot more evictions.

That’s just how the late-stage capitalist housing market works.

And when the bulldozers arrive in the Sunset, tearing down housing without any community input, I think a lot of folks are going to be very unhappy.