>>We need you! Become a 48hills member today so we can continue our incredible local news + culture coverage. Just $20 a month helps sustain us. Join us here.

It’s sadly inevitable that the US will not only experience another horrific mass shooting sometime soon, but also that the only headline to really make sense of the tragedy will be from The Onion. They’ll rerun their infamous headline of “‘No Way to Prevent This’, says Only Nation Where This Happens Regularly.'” There were so many shootings in 2022, that the outlet’s front page was briefly overcrowded with several versions of the article. It happens in this country so often that we risk becoming desensitized to it. No wonder other countries think of it as our real national pastime.

Kaija Saariaho and Sofi Oksanen’s Innocence (with multi-lingual libretto by Aleksi Barrière; US premiere through June 21 at the War Memorial Opera House, SF) takes place in one of those other countries: Finland, to be precise. It should be a happy day as Stela (Dutch soprano Lilian Farahani) has just married the privileged Tuomas (US tenor Miles Mykkanen) in a lavish-but-sparsely-attended ceremony. Stela is new to the country, but feels she’s been warmly welcomed by her new in-laws, Patricia (Canadian soprano Claire de Sévigné) and Henrik (US baritone Rod Gilfry).

What none of them seem to notice is that one of the servers, Tereza (Romanian mezzo Ruxandra Donose), has a personal connection to the groom’s family. She’s a last-minute fill-in who knows that Patricia and Henrik lied about Tuomas being an only child. She knows that Tuomas’ absent older brother was responsible for a horrific school shooting 10 years prior. Of course, that’s public knowledge. Yet what Tereza also knows is that one of the victims of the massacre was her daughter, Markéta (Finnish soprano Vilma Jää).

This sends us on a dual string of events: one reliving the moments leading up to the shooting; the other in the present day, as the ghosts of the victims (Beate Mordal, Julie Hega, Rowan Kievits, Camilo Delgado Díaz, and Marina Dumont) refuse to stay silent.

It’s only right to issue a warning for those sensitive to the topic of shootings: Although the direction by Louise Bakker spares us the sight of anyone being shot, there are several scenes of folks running around covered in blood, of blood being smeared on windows, and even lifeless bodies lying in pools of blood. Furthermore, the entire one-hour-45-min runtime is marked by a persistent sense of dread. This is a story about people with PTSD who are constantly in mourning, save for the one person (Stela) who doesn’t know why anyone would be sad on her happy day.

I can’t speak with experience about the European reaction to mass shootings, but the way it’s presented here is disturbingly similar to the way we Yanks only make a deal of it for a short time. The ghosts of the victims recall a lot of post-shooting political bloviating without any real legislative results. They saw countless think pieces about what the violence says about them as a nation, only for the story to be forgotten by the next news cycle. Eventually, the candles went out at the memorials and the public-at-large forgot about the shock of the tragedy. “Until the next shooting…,” one of the victims says.

Perhaps the best line of the libretto comes when Tereza steps away from her serving duties to voice her disgust at the affluent refusing to have their lives disrupted by a little national tragedy: “Time has not come to a standstill for these people.”

It would be well enough for the story—with its dirge-like compositions by Saariaho, who passed away from cancer in 2023—to be about the lingering dread around an horrific event, but Oksanen’s libretto (as translated by Barrière) aims for greater complexity among its ensemble. The majority of the opera seems to take the traditional stance of simplifying both killer and victims. As the work nears its climax, we learn that the killer may not have been so monstrous, nor the victims so angelic.

It’s a tricky gambit for which the results are mixed. It’s a great to see everyone given shades of humanity, but without spoiling, it veers dangerously close to leaning too heavy on the side of the shooter in the latter scenes. It’s one thing to empathize with a character who does a bad thing (it’s why Stephen King’s Carrie resonates 50 years later), but quite another to try and justify the bad thing. And make no mistake: The shooting was an unforgivable act, no matter what personal pain inspired it.

But perhaps the opera simply stirs so many emotions that plot points are misinterpreted? Sans intermission, the production holds you in its grip and forces the audience to live with its actions the way its characters do.

Said characters are all performed well, yet the livestream I watched from home (the last stream I watched from that particular home) seemed to have mixed the vocals a bit too low. The music came in clearly, as did the pre-show curtain speech, but the proper arias seemed just above whispers. Still, the stream was edited well from the overture to the final bow.

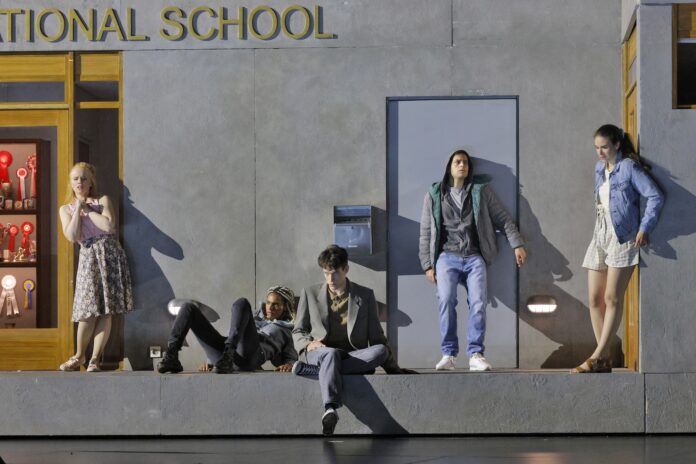

Chloe Lamford’s cube-shaped set is reminiscent of Es Devlin’s similar set from ACT’s recent production of The Lehman Trilogy, as well as Christopher Fitzer’s set for SF Playhouse’s production of The Paper Dreams of Harry Chin. Lamford’s set makes all the scenes and settings fit like pieces of Jenga or a Tetris pattern. I’m growing fond of the set that literally stuffs a lot into a limited amount of space.

When conductor Clément Mao-Takacs took the stand in striped French shirt under a sport coat, it gave me the odd impression that there would be some sort of light-heartedness to the story’s heavy material. To my surprise, the music is as consistently melancholic as the story it accompanies. That’s probably for the best. I can’t say that Innocence is a happy story by any means, but it’s certainly a well-produced one.

INNOCENCE runs through June 21 at the War Memorial Opera House, SF. Tickets and further info here.