You may know someone who tried to enroll in a class at City College of San Francisco for the fall term or during the last year, and, like hundreds, if not thousands of others, was unsuccessful.

Over the last 12 years, the college’s administration has reduced thousands of scheduled classes from the Fall and Spring terms. Not counting summer school, the number of credit classes declined from 6,384 in the 2011-12 school year to 3,538 in 2023-24, and non-credit classes during the same period went from 2,392 to 542.

For the Fall 2024 term, many classes essential to the education of students at CCSF were fully enrolled months before the start. According to an Inside Higher Education story in early June, more than two months before the school term began,

“A dearth of introductory English classes at City College of San Francisco has led to wait lists of upwards of 200 students, some of whom need the course to complete their programs and get their degrees.”

A week before the start of the Fall 2024 term, almost 400 students were on waitlists for English 1A. The waitlists would have been even longer, but they are limited to no more than ten students per class, and students can be on a waitlist for only one English 1A class.

Many other classes were also fully enrolled with waitlists. Biology classes had 402 students on waitlists, and Chemistry waitlists had 114 students.

Many scheduled classes in the arts were fully enrolled soon after the start of registration in early May. For some classes, the registration system did not allow for a waitlist that would result in students receiving a message when an opening occurred.

A counselor felt prompted to recently post on the faculty exchange,

“As a counselor, I see a constant stream of students who cannot access classes at CCSF…right now (and for the past 3 years in particular), we DO NOT HAVE ENOUGH CLASSES FOR OUR STUDENTS. I regularly refer CCSF students to other colleges to either get a full-time load [of classes] or to round out their schedule…”

Interim Chancellor Mitchell Bailey and other administrators will tell faculty we should seek to grow enrollment and, in Bailey’s words, have a “student-first approach.” But this is stymied by not scheduling more classes. When asked about adding more classes, Bailey stated that having waitlists is not unique to CCSF, and that he is working to add more classes “responsibly.” However, despite enrollment growth and the large waitlists, there are fewer classes scheduled for Fall 2024 than last year.

In recent years, the administration’s rationale for scheduling fewer classes has been the claim that the college faces serious budget deficits. Supposedly, to save money and address the deficits, they reduce the number of classes. For example, for the Fall 2024 term, there are 57 English 1A classes scheduled. As recently as Fall 2021, 78 sections of English 1A were available.

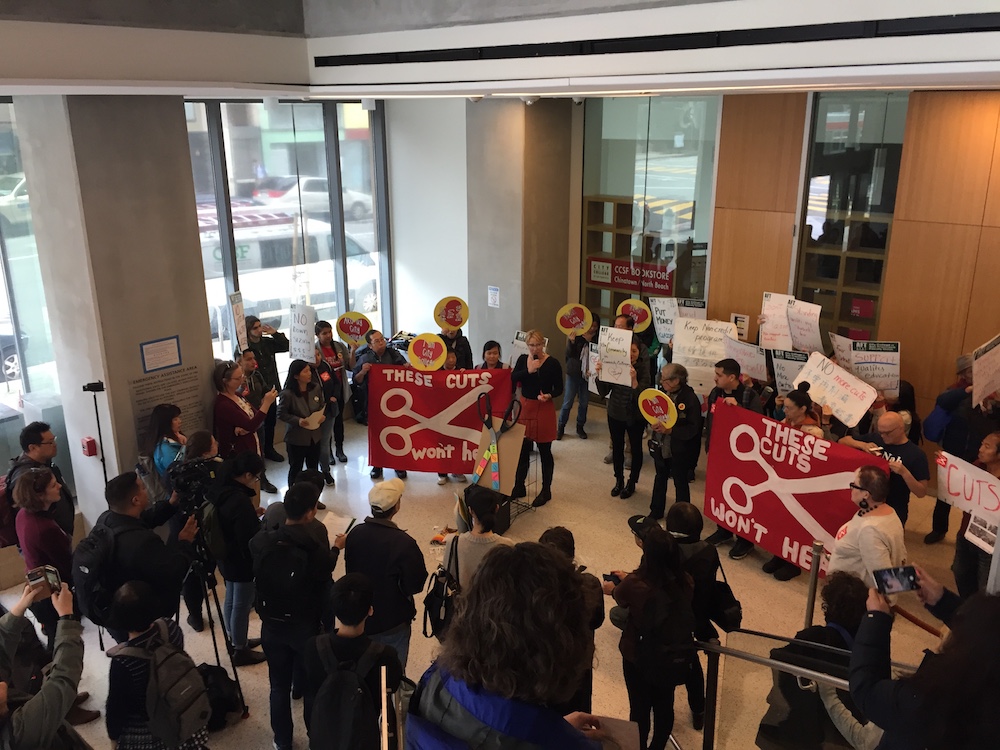

When the faculty union has analyzed the budget, they have found that the administration’s claimed deficits are actually surpluses. Yet, the union’s findings have been ignored by the administration.

The union established an alternative budget in 2022 that showed no cuts were necessary, nor was the firing of 38 full-time tenured faculty, eight of whom, surprise surprise, had been teaching in the English Department.

The administration also projects future deficits which they see themselves currently addressing by putting more money into the reserve account. Yet, the administration’s claimed future deficit is partly generated by their planning for [page 19] a 55 percent increase in their salaries from $5.76 million in school year 2022-23 to $8.96 million in 2027-28—an increase coming to more than one-third of their projected deficit for that year.

According to the administration, the reserve account holds more than $30 million, well above the legal requirement. Why can’t some of that money be spent now to provide students with the classes they need? After all, isn’t the purpose of the college to provide students with classes?

As long as the administration refuses to provide the community with classes students need and want, many students will be deprived of educational opportunities.

Most CCSF students are working class people of color. By not offering enough classes, here, in anti-racist progressive San Francisco, the CCSF administration, that claims to favor policies that promote equity, is helping to reinforce structural classism and racism as it contributes to the assault on public education.

Rick Baum has been teaching Political Science at City College of San Francisco for more than 25 years and is a member of AFT 2121 and CCSF HEAT.