I’ve always been fascinated by the similarities between the words sowing and sewing. I used to mix these homophones up as a child, imagining a needle and thread stitching soil together instead of seeds falling into small holes. Sowing is often masculinized while sewing, in contrast, is a more feminized tradition. The process of threading at least three layers of fabric together is ancient. But here in the United States, women were routinely trained to stitch, sew, and thread as part of preparation for domestic labor within the home.

Women deposited their emotions into the practice, including grief; for Black women, this domestic labor was also often forced labor. So it isn’t surprising then that Black women’s patchworks of colorful cloth spoke volumes, containing emblems of Africa, messages of spiritual salvation, and the promise of freedom. Fortunately, this extraordinary quilting tradition has garnered widespread notoriety in recent decades, even adoring the walls of prestigious museums like the Smithsonian.

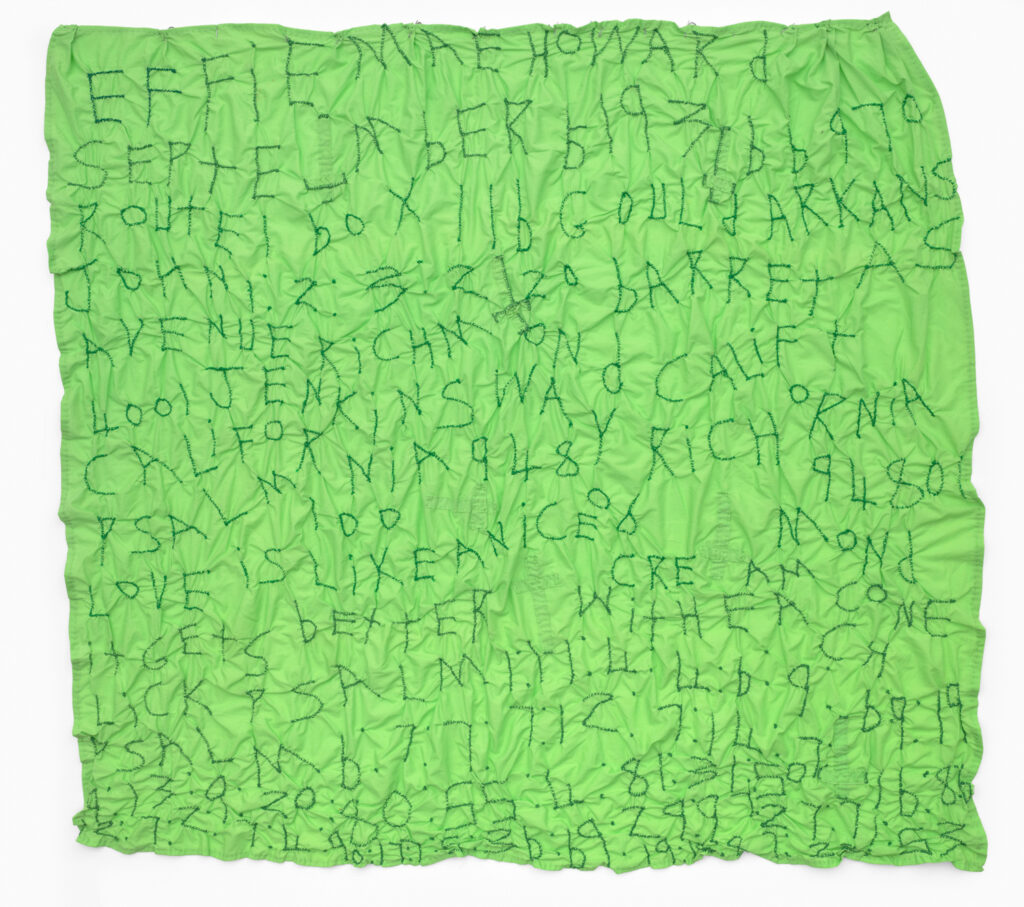

One Richmond-based quilting visionary, Rosie Lee Tompkins, is known for pushing the envelope within the African American quilting tradition itself. She appears to have been a somewhat introverted and private person. Her artist name is even a pseudonym for Effie Mae Martin Howard. Nevertheless, Tompkins’ innovative approach to the practice is loud.

It caught the attention of an Oakland-based collector by the name of Eli Leon. Leon was fascinated by Tompkins’ one-of-a-kind use of color and pattern. Perhaps he felt that her style hinted at complex emotions brewing below the surface, or psychological challenges he too faced.

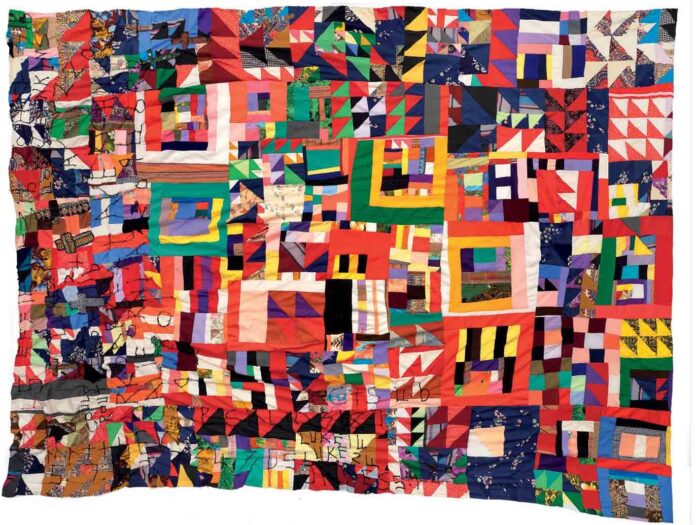

While it’s quite common for quilters to measure and plan out pieces, Tompkins’ “crazy quilts” were almost entirely improvised. They push past utility and in the direction of abstract art. In fact, her quilts are so avant-garde that The New York Times dubbed her a “radical” quilter last year.

Tompkins’ captivating works can be discovered on display via BAMPFA’s exhibit: “Rosie Lee Tompkins: A Retrospective.” Leon gifted over 3,000 quilts to the BAMPFA, which has perhaps inadvertently made the museum a leader in the preservation of African American quilts nationally.

Tompkins, who passed away in 2006 at the age of 70, incorporated recycled materials in her quilts, from men’s neckties, to denim, to velvet. She credited God for bestowing her with quilting capabilities, and you do see Jesus’ face popping up in some of the pieces. But I found myself drawn to the quilts with obvious themes, however subtle.

One large quilt appears to be an Ode to California, the state that Tompkins settled in after having grown up in Arkansas. It combines it’s bright background with many bits of beading and embroidery. It looks more like a map, a homage to the sunshine state, than a bedspread. I loved the nod at allyship, an African American woman making a quilt of love for Cali’s Indigeneity.

I am also mesmerized when Tompkins creates patchworks of lettering against a monochrome background. It feels futuristic. I can see her images on a runway model adorning a fit described as “streetwear.” And I’ve seen Black girls wearing denim-on-demin on multiple occasions, which makes me wonder if they were inspired by their mothers or grandmothers’ approach to pattern.

Tompkins was also known for using darker colors, black and dark blue. Her range is unmatched. Even after spending hours looking at the quilts, it feels like you’re merely scratching the surface. The BAMPFA exhibit is impressive, it includes a virtual tour that provides context for each quilt as well as several programs that invite other quilters to engage with the body of work.

Rosie Lee Tompkins was no doubt brilliant in her approach. I wonder what would have happened if she had used paint and canvas as her materials. How did Tompkins’ access to quilting (and perhaps simultaneous exclusion from other forms of artistic expression) impact the way she saw herself as an artist? Did she even feel like an artist, as much as a messenger of God?

You can view a selection of Tompkins’ quilts online here as well as the video tour above. And last February, BAMPFA offered a window into her contributions to contemporary art, with a conversation is called “Colloquium: Re-visioning the Art of Rosie Lee Tompkins.” It’s worth a watch to understand more of this fascinating maker’s talent and influence.