When Bill Russell died on July 31 at the age of 88, the Oakland-raised athlete was honored by the San Francisco Giants with a moment of silence at Oracle Park. Russell was not only the first Black player to attain superstar status in the NBA, but also went on to become the best player in NBA history.

Russell’s performances on the court are unparalleled in a sports culture obsessed with statistics and analytics: his teams competed for 16 championships between 1955 and 1969, including two NCAA titles, an Olympic gold medal in Melbourne in 1956, and 13 NBA titles with the Boston Celtics. Russell’s teams won 14 of them, according to the journalist at large Bob Ryan. Not bad for a kid out of McClymonds High School in Oakland.

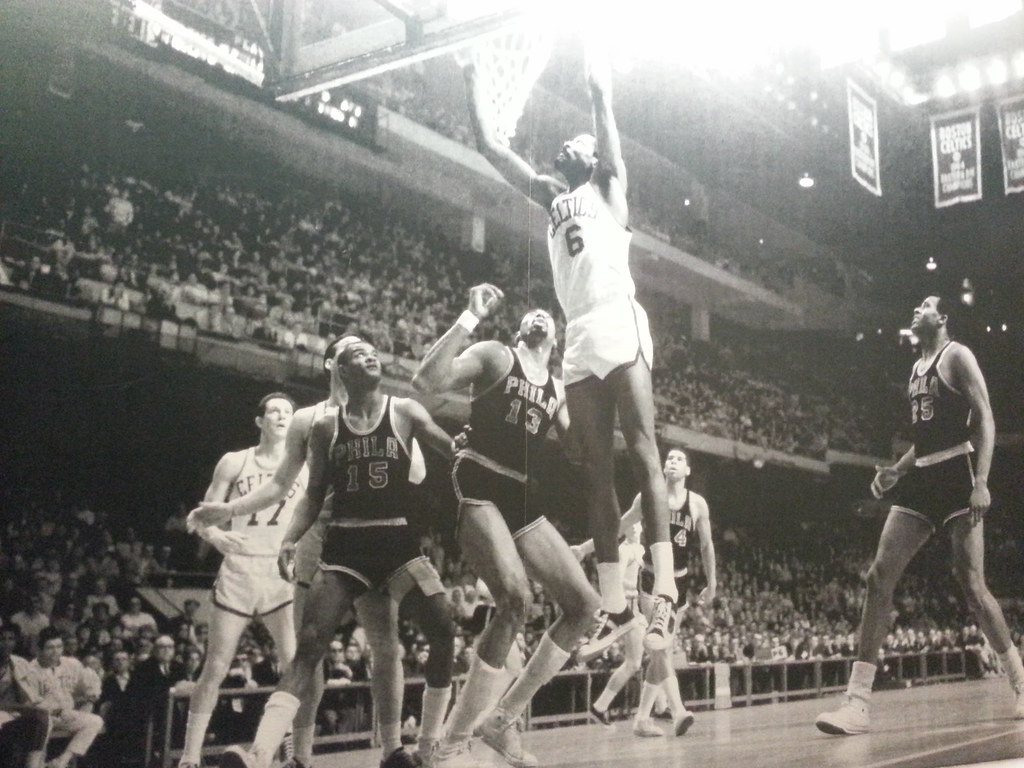

Bill Russell is 21-0 in 21 winner-take-all games, which means he has won every NCAA title game, every Olympic medal round game, and every NBA finals series in which he played. On the court, he helped his team rather than himself. Most nights, he’d wind up with more rebounds than points. He blocked shots too—though it’s hard to say exactly how many, since even through the first half of his career, the NBA didn’t even track blocked shots. Unlike in modern NBA play, where such rejections typically go into the stands, and players often taunt after making the rejection, Russell usually directed the block towards a teammate in order to initiate an offensive march up the court.

He kept it moving.

Is it inappropriate to compare eras? Yes. If you use an offensive racial term in the stands today, you will be expelled, fined, and in some circumstances, banned from the venue. But back in the day, drunken fans had their way with Russell, whether he was playing in the renowned Boston Garden or away games.

“To me, Boston itself was a flea market of racism,” Russell wrote in his 1979 memoir Second Wind, according to his obituary in The New York Times. “It had all varieties, old and new, and in their most virulent form. The city had corrupt, city-hall-crony racists, brick-throwing, send-’em-back-to-Africa racists, and in the university areas phony radical-chic racists (long before they appeared in New York).”

Boston, home of the Bruins, was a hockey town when Russell joined the Celtics, and the Garden was barely 70 percent full throughout his team’s first six title campaigns. By the time he was well into retirement, Russell would see the same city elevate Larry Bird, who won three NBA titles, to God status.

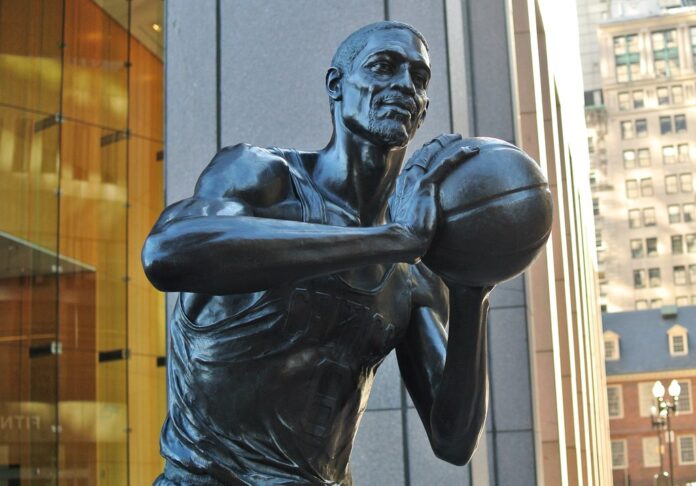

He himself wouldn’t have a reconciliation with the Celtics organization and the city until the late ‘90s. By then, Boston’s attitude had changed, as had Russell. Both had adopted new appreciation for each other, and he saw it as his duty to make a connection with these new-generation Celtic fans.

Off the court, Russell was larger than life, too. He was even a pallbearer for Jackie Robinson’s funeral. Russell once said that barrier-breaking baseball legend took “us from point A to Point B.”

Russell protested at the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, and was positioned in the front row of the crowd to hear the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. deliver his “I Have a Dream” speech. Russell went to Mississippi after the civil rights activist Medgar Evers was murdered, and at Evers’ brother Charles’ behest, opened an integrated basketball camp in Jackson, despite death threats directed at him all along the way.

Russell was also among the group of prominent Black athletes—which also included Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Jim Brown and Muhammad Ali, which today looks like a Mount Rushmore for Black excellence—who supported Muhammad Ali when he refused induction into the armed forces during the Vietnam War, citing his religion forbade him from serving.

All of these radical-for-their-time actions were carried out by Russell without fear of repercussions from commercial sponsors or The Boston Celtics. Russell lived his life his way, and damn anyone who attempted to tell him otherwise. John Thompson, famed coach of the iconic Georgetown Hoyas from 1972-1999 was a backup center to Russell on the Celtics. Thompson, who was 6’10 and 269 pounds, once told reporter Tony Kornheiser that the only time he felt safe in the city of Boston was when he was in Bill Russell’s presence.

President Barack Obama awarded him with the Presidential Award of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian award, at the White House in 2011. Upon Russell’s passing, the president spoke of the fortitude that shaped the man’s life.

“Perhaps more than anyone else, Bill knew what it took to win and what it took to lead,” said Obama. “On the court, he was the greatest champion in basketball history. Off of it, he was a civil rights trailblazer—marching with Dr. King and standing with Muhammad Ali. For decades, Bill endured insults and vandalism, but never let it stop him from speaking up for what’s right. I learned so much from the way he played, the way he coached, and the way he lived his life.”

But it was a non-quote from a basketball pioneer of a newer age that summed up Russel’s legacy.

ESPN commentator-at-large Michael Wilbon remembers that once, the SportsCentury program on ESPN voted Michael Jordan the greatest athlete of the 20th century. But upon finding out the news, MJ was angry.

Wilbon asked him why, and Jordan replied: “Do you think I am ever going to let the sentence come out of my mouth that I am better than Bill Russell?”