One of The Velvet Underground’s greatest advantages—the band’s discordant drone and jarring lyrics—was also its greatest liability.

Named after Michael Leigh’s S&M-themed novel, the pioneering ‘60s group lived up to its moniker, singing streetwise songs about homosexuality, drugs, and kinky roleplay.

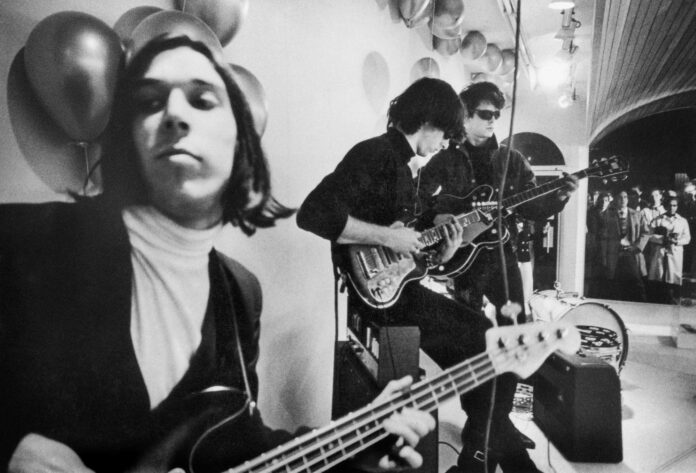

Too out there for the times, The Velvet Underground—composed of inconoclast singer/guitarist Lou Reed, classically trained Welsh violist John Cale, “sterling” guitarist Sterling Morrison, androgynous drummer Moe Tucker, and sometimes stoic German-actress-turned-singer Nico—achieved little success or critical recognition in its six-year span.

But Andy Warhol’s Factory band, which over five albums produced such now-beloved tracks as “All Tomorrow’s Parties,” “Sweet Jane,” and “I’m Waiting for the Man,” has since sparked myriad musical movements including glam rock, punk rock, and shoegaze.

The group would also go on to inspire filmmakers like Todd Haynes, whose own work—1987’s Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story, 1998’s Velvet Goldmine, and 2007’s I’m Not There—tackles similar themes of sexuality and outsiderhood.

So when an invitation came from Universal Music Group’s David Blackman and Lou Reed’s widow, avant-garde artist Laurie Anderson, to make the definitive documentary about The Velvet Underground—Haynes jumped at the opportunity.

“I was just immediately intrigued by the idea of the challenge of doing a doc on The Velvet Underground, a band that I love, which doesn’t exist in all the traditional places that we assume music subjects reside in, but so uniquely within this avant-garde culture of New York City of the mid-’60s,” Haynes told 48 Hills. “I just wanted to dive in deep.” (Read 48 hills movie critic Dennis Harvey’s review here.)

To capture the era in a more immersive way and even mirror the multi-sensory experience of Velvet Underground shows (so ahead of their time with projected films and hypnotic lights that San Francisco promoter Bill Graham’s own psychedelic presentations appeared dim in comparison) Haynes includes rare archival footage, Warhol movies, and scintillating recordings, along with interviews with surviving Velvets, Cale and Tucker, and many of their creative collaborators including Warhol superstar Mary Woronov, Modern Lovers’ musician Jonathan Richman, and experimental filmmaker Jonas Mekas.

I spoke to Haynes about The Velvet Underground movie (now playing at Embarcadero Center Cinema, the Roxie, and the Balboa Theatre and streaming on Apple TV+) about first discovering the group, their enduring impact on his work, and how the band’s extreme trangressiveness made even San Francisco hippies look positively bourgeois.

48 HILLS I know you first discovered The Velvet Underground in college. I have to imagine that hearing Lou Reed’s lyrics about gay sexuality hit you hard as a young queer man.

TODD HAYNES It wasn’t even the lyrics. It’s almost like something John Lennon once said about Bob Dylan: you don’t even have to understand the words to know what he’s talking about. I think all great music has to communicate from the inside out and hit you from within—and The Velvet Underground does that.

What they evoke is a world that’s just different from other worlds that had been explored at that point in the ‘60s, and arguably by any band ever. Sure, they opened the door to all other dark-themed music, whether it’s glam rock exploring sexual identity or punk rock or grunge, but there’s something uniquely transgressive in the work of The Velvet Underground. It’s haunting and the drones and the resonance and the echo chamber of this music pull you into it.

I just felt transported somewhere that I wanted to be and I felt like it was inviting me to respond to it in a creative capacity. That’s very unusual for even music one loves. You don’t always feel you could do something yourself that has a meaning that touches some of these other places in your own life.

48 HILLS Brian Eno once said: “The Velvet Underground didn’t sell many records, but everyone who bought one went out and started a band.” How did The Velvet Underground shape your future art?

TODD HAYNES I think it’s something about an affirmation of marginality and the sense of standing outside normative conventions about identity and sexuality and the choices that we’re supposed to make toward success. This band was describing something else, other paths that should be taken and places that don’t always feel great. That through levels of feeling displaced or marginalized or even having contempt directed toward you—there’s a certain strength that a person can gain about asserting oneself in the face of that.

To me, it’s not that far from the messages I found in the writing of Jean Genet (an important reference point for my first feature film, Poison), who basically was saying “Yeah, I accept being called homosexual; I accept being called criminal; I accept how all of those things upset the norms of society and provide a critique of those norms.”

48 HILLS So many artists connected to this story, including Warhol, Nico, Morrison, and Reed had already passed away when you began working on this project in 2017. Filmmaker Jonas Mekas, who appears in the film, died during the making of the movie. So I have to imagine that getting firsthand accounts from people who were actually there must have felt like a race against time.

TODD HAYNES That was a real poignant but urgent drive and, of course, starting with Jonas who just turned 96 when we filmed him. But in many ways, we feel like all of the people who are still here are survivors from another planet and another time. They’ve survived so much and borne witness to it.

John Cale feels like he is imbued with a goal of survival. I don’t know that I’ve ever seen anybody in his late 70s who is more glowing and handsome and ebullient than John Cale. There’s something in that, in what they’ve seen and what they’ve survived that also gives them a force on this earth. But in the lines of their faces and in the contrast of what they looked like then and what they look like now, time is a precious factor in the film—and you feel it.

And I can’t not factor in the reality that this film came out of the end of the Trump years, when we started to make it. Then, the first season of COVID hit and we’re all in isolation and the world feels very uncertain.

And here we were with this incredible moment we had with the films that survived and the amazing artists I got to speak to in person who gave of themselves and wanted to participate. It felt like something very precious that we were trying to preserve and share and keep in context, so it’s something we could access in this film—a sense of what it is like to be there.

48 HILLS In sifting through footage of The Velvet Underground and the Factory during the “first season of COVID,” I imagine that the contrast—between the mid-’60s, when so many people were coming together to engage in creative pursuits and today, when so many people are isolated as a result of COVID or even the digital era—must have appeared incredibly stark.

TODD HAYNES Some very practical changes have defined a real difference in the way we commingle as a culture, which was only furthered by COVID. But it’s already the way that digital culture and the way we live on our screens pull us apart from each other.

It was different in the ‘60s and in many historical moments that you see people smashed together physically in the same space and sharing experiences and ideas in proximity of each other, and there’s no question that there’s something really exciting and vital about that and something to not forget is a factor in rich artistic movements that produce new ideas. There’s a reason why these things happen very quickly when there’s a lot of combustion of ideas and of people in the same place.

48 HILLS One of the points made in the film is that what was happening in New York City with the amphetamine-addled avant-garde art scene that The Velvet Underground was a part of was diametrically opposed to what the hippies were doing in San Francisco during the Summer of Love. How would you compare the two scenes?

TODD HAYNES Well, sure there was a lot of personal expression going on in the ‘60s all over the place and that’s true for not just the counterculture on the West Coast, but also all the great artists that we think of like The Beatles, Bob Dylan, Aretha Franklin, and Miles Davis. There was an incredible flexing of a new sense of vitality around who you were and what you believed. The Velvet Underground just happened to be describing different kinds of experiences that weren’t always affirmative, that weren’t always positive.

And yes, I think it’s important to look at some of the contradictions in the hippie culture and how sexist it was and how conventional it was in some ways and navel-gazing and how it wasn’t necessarily directed toward positive outcomes or changes that were palpable.

It’s not as if The Velvet Underground were politically active. That wasn’t what they were doing. They were examining the darker kinds of feelings and vulnerability and doubt and transgression, and they were looking at the world through a different lens. I think that’s important to identify and it’s also a way of explaining why people were freaked out by them at the time and why it took a lot longer to be accepted than the anti-war movement was. I think it’s important to say why—and a lot of it, I think, has to do with queerness.

The Velvet Underground is now playing at the Roxie, Balboa Theatre, and Embarcadero Center Cinema and streaming on Apple TV+.