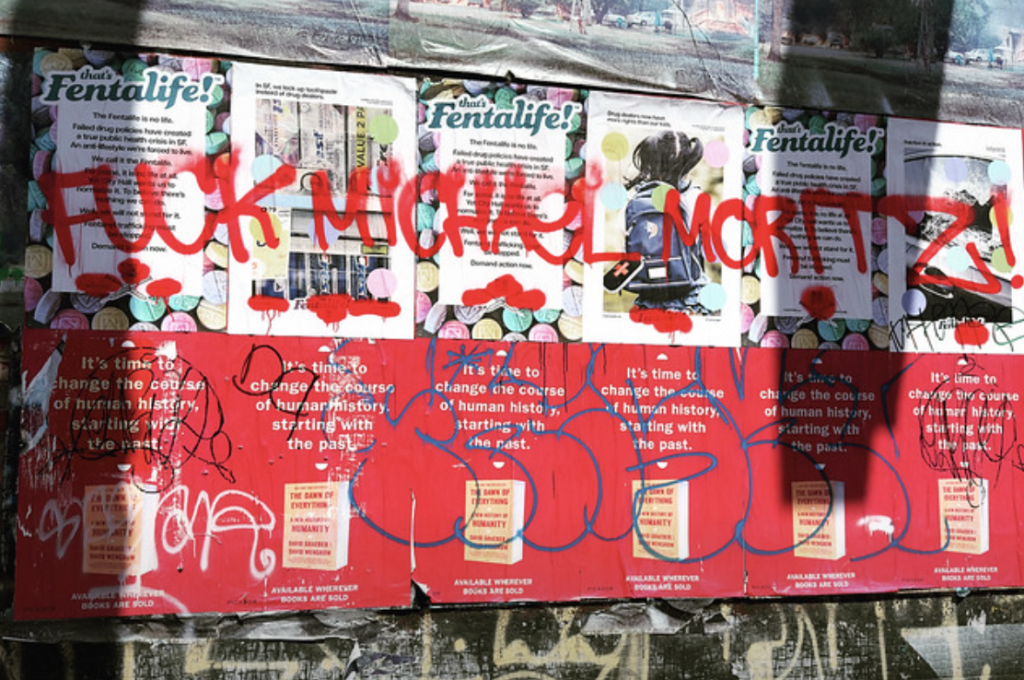

Flashy and colorful in pastel tones, the advertisements were wheatpasted across San Francisco last Tuesday, packaged with a new, briefly trending Twitter hashtag re-branding the inarguably tragic fentanyl crisis. “#That’sFentalife,” announced the PR campaign, said to cost $300,000. Fentanyl is deadly awful and highly addictive, they told us. As if we didn’t know already.

In a strictly PR sense, the campaign did grab some headlines and lots of clicks. Good metrics for the ad firm and the moderate/centrist campaign group TogetherSFAction, which, not coincidentally, aims to pour $3 million into the next two local elections, financed principally by Sequoia Capital investor and SF Standard owner Michael Moritz.

But does making headlines and proliferating online chatter equal success? Unfortunately, for all its snazzy PR creativity, the TogetherSF campaign is misleading, cynical, unnecessary, and just plain weird. I’ll get to the misleading and cynical parts in a moment. First, the weird and unnecessary.

Weird: The campaign posters look like 1970s cigarette or soda ads, as if they’re for Newport smokes or Fanta soda. The top-level messaging is bizarre and profoundly tone-deaf, clearly insinuating that fentanyl is a lifestyle choice rather than a deadly addiction spawned by a host of complex root causes. In fact, the campaign’s website even says that: “City Hall is forcing us to live an anti-lifestyle. We call it the Fentalife.” Seriously? People are dying in the streets, and this is what they come up with in the name of change?

This Reaganesque, “Just Say No” talking point is offensive on its face—nobody is celebrating being addicted to a drug that imperils their existence. Drug addiction is a disease, not a lifestyle choice, as countless analyses show. Reviving the stale and failed “lifestyle” myth only further stigmatizes substance addiction, setting back the treatment efforts the campaign claims to support.

Unnecessary: TogetherSF’s ad campaign merely repeats a much-traveled conservative talking point, pretending that they alone are acutely aware of the crisis and must “shock” and alert everyone. We already know there’s a horrible and tragic drug addiction crisis. That’s precisely why some city leaders, like supervisors Dean Preston and Hillary Ronen, are pushing hard for wellness hubs to help address the situation. It’s why there are already treatment centers and harm reduction efforts across the city—both of which urgently need expansion.

Campaign supporters insist it’s a success because, hey look, we’re all talking and writing about it now—but it hasn’t created a single new fact or argument that wasn’t already widely known and has proliferated harmfully misleading ideas that only confound solutions to the crisis.

Here’s where the unnecessary and the misleading conspire to make this ad campaign more harmful than helpful. Pretending that they must “shock” us into recognition of a widely known problem, and pretending that city leaders and policymakers are either doing nothing or, worse, enabling the crisis, simply regurgitates a conservative narrative peddled broadly by Fox News and others, most recently the deeply biased and bizarrely uninformative CNN special, “What Happened to San Francisco?”

Misleading: Among many, here’s one blatant false talking point with which the campaign has laminated the public space: “We call it the Fentalife … City Hall wants to normalize it. To believe there’s nothing we can do.” Now, PR language is intended to shock and provoke, but this is just plain false and cynical, and the campaign surely knows it. After all, TogetherSF Action’s executive director, Kanishka Cheng, is a former staffer for Mayor Breed.

It’s true that city leaders—principally the mayor who controls the budget and city departments—can and should do more to expand treatment on demand and supportive housing that includes treatment and recovery services. But the notion that “City Hall wants to normalize it” is just sinister and bizarre.

Also misleading is the campaign’s constant insinuation that fentanyl is a San Francisco problem—based on “a failure of our elected officials”—rather than a national one. Nobody denies that San Francisco has a serious fentanyl addiction crisis on its hands; but pretending this is about local politicians’ decisions ignores all the vast evidence of a nationwide fentanyl epidemic that crosses party lines. The “Fentalife” campaign’s fixation on local electeds (well, they do thank some, like Mayor Breed, Governor Newsom, and Rep. Pelosi, for bringing in the national guard, which, predictably, hasn’t helped anything) suggests that TogetherSF’s project is more about upcoming elections than about concrete immediate change.

As The Chronicle’s Nuala Bishari reported, those who work directly on the drug addiction crisis in the Tenderloin find the campaign counter-productive: “It’s one of the most disgusting, offensive, tone-deaf responses I can imagine to the public health crisis we’re in right now,” Laura Thomas, director of harm reduction policy for the San Francisco AIDS Foundation, told Bishari. “We are running out of Narcan pretty much every week. The numbers of people coming in for services is skyrocketing. And the best response these people can do is put up pastel ads in the neighborhood mocking people?”

Ultimately, the #ThatsFentalife campaign seems a poor use of resources. Rather than reiterate well-known realities, why not spend the $300,000 either directly on street-level drug treatment services, or seeding a huge fundraising campaign to greatly expand treatment on demand? Or, better yet, why not use the funds to create a ballot measure that taxes the city’s richest folks and dedicate the revenue to treatment on demand?

Bishari calculated that the PR campaign money “could buy San Francisco 100,000 vials of generic, injectable naloxone or 12,631 doses of brand-name nasal Narcan. It could pay for 927 days of residential substance use treatment.”

Now, imagine for a moment if TogetherSF and its allies spent that $300K launching a direct fundraising campaign for immediate expanded treatment of the fentanyl addiction crisis—tapping their vast networks of ultra-wealthy friends to kick in many millions of dollars? That would be a lot of residential treatment.

Instead, TogetherSF chose the snarky political route (no surprise, really, given its track record so far, and its funding from Sequoia Capital’s Michael Moritz, who also bankrolls other political groups and The SF Standard online newspaper). It says here, based on my decades of observing and reporting on politics in SF, that this campaign is more about saturating the public mind to set the tables for the next election cycle—elections on which their allies such as GrowSF, and Neighbors for a Better SF (also financed heavily by Moritz) are already spending vast sums to upend progressive supervisors.

Problem is—those few progressive legislators have minimal power as it is (especially compared to the mayor, who controls the city budget, department heads, and much more), and they’re the only ones actually proposing to repair the harm through wellness hubs and expanded street-level public safety measures.

Here’s where cynical comes in.

Cynical: The #ThatsFentalife campaign seems to advocate for some of the very things—such as “funding more city-sponsored recovery programs”—that are most strongly supported by the progressive supervisors that the group and its political allies routinely lambaste.

One thing that worked, despite its controversies and imperfections, was the Tenderloin Linkage Center, which, in its 11 months, “reversed 332 overdoses and linked 1,529 clients to housing or shelter,” The Standard reported citing city data. Science has repeatedly shown that harm reduction works to save lives and improve public health. Certainly, we can insist on improvements that combine harm reduction with encouraging treatment, something already being promoted by San Francisco’s Overdose Prevention Plan.

Some of the city supervisors who get attacked the most by TogetherSF—Dean Preston, Hillary Ronen, Aaron Peskin, and Connie Chan—are the very ones pushing for more wellness hubs to fill the gap, save lives, and promote treatment services. But if TogetherSF and its well-heeled allies get their way in the next election, some of the city’s strongest advocates for expanded treatment on demand would be gone.

Let’s be honest: Everybody knows there’s a deadly crisis in our streets. It’s not simple, and has multiple complex root causes (yes, root causes, not lifestyle choices). Fixing it will take time and serious money. In terms of the publicly visible, street-level addiction, helping thousands of homeless people recover sustainably from addiction requires supportive housing, harm reduction (such as safe supervised injection sites that save lives until someone can get into treatment), and treatment and ongoing recovery services. That means major funding. Existing public funds may not be enough. To truly fix this crisis may require taxing the very rich and taxing and/or suing the corporations tied to the opioid epidemic (see the city’s recent $230 million win over Walgreens).

The question is—who’s going to support these public investments in our city’s health and wellbeing? Well, the very supervisors whom TogetherSF and their allies like GrowSF consistently attack, such as Preston, Ronen, Peskin, and Chan, are the very ones with a track record of supporting those investments.

Perhaps the next six-figure investment by TogetherSF and its allies should be a ballot measure that taxes the city’s super-rich and the corporate purveyors of opioids and dedicates that revenue to supportive housing that provides treatment on demand. If, that is, they’re serious about fixing the deadly tragic crises in the streets.

TogetherSF director Kanishka Cheng and staff did not respond by press time to multiple requests for comment for this piece.

Christopher D. Cook is an award-winning journalist and author who has lived in and reported on San Francisco for nearly 30 years. He also writes for Harper’s, The Atlantic, The Guardian, Mother Jones, The Los Angeles Times, and others. Contact him through www.christopherdcook.com.