“Bodily autonomy!” is among the things chanted by high school-style cheerleaders who provide a running thread in Give Me An A, an anthology feature out On Demand from XYZ Films this Thurs/29. Its subtitle is A Reaction to the Overturning of Roe v. Wade, so you can guess what that “A” primarily stands for. As is typical for this sort of omnibus, the segments by 17 women filmmakers are highly variable. Some lack any clear point, while others lean on over-familiar satirical devices (a mock sitcom, mock commercials) without much wit. But the pervasive sense of outraged disbelief is apt, needless to say, and the contents cover a diverse range of takes on the issue.

Among the best bits are a fantasy of how different life (let alone hookups) might be if men had to shoulder the main burden for unplanned pregnancies; an encounter between an expectant mother in the carpool lane (she’s “driving for two”) and a traffic cop; and a dead-serious bit in which a grocery store is a front for a no-longer-legal but desperately needed different kind of business. Though not exactly star-studded, the films sport appearances by some recognizable faces, including Virginia Madsen and Alyssa Milano.

Of course abortion is not the only frontier on which the alleged political party of “small government” has striven to re-assert control over individual autonomy of late. And sneaking in at the last moment to take advantage of Pride Month, a number of other new releases this week provide disparate perspectives on how bodies, identities, sexual orientations, et al. are hardly a one-size-fits-all matter—no matter how strenuously you try to legislate them into conformity.

Among movies we were unable to screen in advance, the one theatrical release (on Fri/30) is Julie Cohen’s documentary Every Body. Using three leading activists as protagonists, it’s a look at intersex people—that small percentage (estimated as one in two-to-five-thousand) born with “ambiguous genitals” that complicate simple gender assignment. (Among the terms formerly used to describe them were “hermaphrodite.”) Many are forced into premature surgeries to “correct” the “problem,” and/or zealously hide their condition. But recently they’ve started to claim visibility and rights as a community. It is a measure of skittishness around any non-binary identity that the as-yet-unreleased film already has a pile of lowest-possible “user ratings” on the Internet Movie Database—because, no doubt, many conservative posters are triggered by the very idea. Even though intersex persons didn’t “choose” to be so, they’re born that way.

Also unpreviewed but premiering on HBO’s various platforms are two more documentaries. Arriving Tues/27 from Oscar-winning Bay Area duo Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman is Taylor Mac’s 24-Decade History of Popular Music, a condensed concert film/behind-the-scenes record of the unclassifiable multihyphenate talent’s marathon performance marching though American history and song—with plenty of cultural inclusivity and polymorphous drag fabulosity, natch.

The next day brings Stephen Kijak’s Rock Hudson: All That Heaven Allowed, an appreciation of the once hugely-popular movie star through the framework of the closet he lived in. While his sexuality was an “open secret” to much of Hollywood, such was his commitment to old-school “discretion,” he continued denying it even as he was dying of AIDS. Nonetheless, his 1985 demise at age 59 was a watershed moment in public awareness of (and education about) the epidemic.

Pushed out of the closet in a different way is the character played by Will Masheter in co-scenarist/co-star Hugo Andre’s debut directorial feature Makeup, which Red Blazer Productions releases to digital platforms on Tues/27. Dan is a handsome thirty-ish London stockbroker who’s just rented a room in his flat to fussily withdrawn French food critic Sacha (Andre). Their interactions are awkward at first, but soon become more frequent—because Dan loses his job after a couple noxious alpha-male coworkers spy his nervous maiden cabaret performance in glamorous drag, a hitherto private passion.

These actors are capable, and Makeup is stylish on slim means, reflecting the director’s apparent background in advertising. But their script sure could have used more work—very short on incident and character backstory, it’s got about twenty minutes’ worth of material that gets stretched awfully thin to ninety.

If Andre’s film affirms crossdressing in itself as a liberating lifestyle choice (we never find out if Dan is gay, or his housemate either), the French rediscovery A Woman Kills offers a throwback to the bewigged sexual repression/dysfunction terrors of Psycho and Dressed to Kill. Unlike them, however, it has the quasi-fact-based air of a docudrama, alongside elements of film noir and Nouvelle Vague.

As if we’re watching a newsreel at the start, a narrator informs of the execution of one Helene Picard, a troubled woman frequently at odds with the law. It is assumed that with her death, a rash of prostitute killings will cease. But they do not—and we increasingly wonder if Louis Guilbeau (Claude Merlin), an ex-soldier civil servant who happens to be involved romantically with a police investigator (Solange Pradel), has been the culprit all along. But his penchant for committing these brutal crimes in full female garb throws the authorities off for some time.

A no-budget B&W feature that was originally unable to find distribution amidst censorship issues, Jean-Denis’ first feature is rough-hewn, uneven, yet full of adventurous idiosyncrasies. It’s got a lot of female nudity without feeling exploitatively prurient; has an eccentric soundtrack of original songs commenting on the story; and is vividly filmed on downscale locations revealing a hidden Paris made even more alarming by being partly shot amidst the chaos of May 1968. (Intriguingly, Bonan also acted in Jean Rollin’s own notorious debut feature Rape of the Vampire, released during that same turmoil.) It is perhaps more of a fascinating curio than any neglected classic. But Merlin throws himself into his tortured role with impressive commitment, bringing pathos as well as madness. A Woman Kills is surely worth a look for anyone who treasures such odd, obsessive cult indie noir nightmares as Blast of Silence and Daughter of Horror. It has just been released by Flim Movement on Blu-ray, and to their streaming platform.

The same label is also releasing (albeit just to streamer Film Movement Plus at the moment) the much less hair-raising Lola on Fri/30. Receiving news that her mother has died of cancer, the titular pre-op teenager (Mya Bollaers) is despondent, not least because mom was her primary financial and emotional support. Providing neither is dad Philippe (Benoit Magimel), who threw his only child out two years earlier and seemingly has no ability or desire to grasp the pink-haired skateboarder’s trans identity. A volatile reunion turns into a shotgun marriage of a road trip, as Lola nee Lionel insists on going along as dad drives to scatter ashes at a beloved shoreline.

You know where a movie of this general type is heading: Though a lot of old-wound-tearing arguments to reconciliation and a new level of mutual understanding. While admittedly she’s had more than her share of hardship for an 18-year-old, Lola is a bit of a brat—at times you wish she’d make the effort to talk to her father and overcome his prejudices, rather than impulsively ramping up their conflict. Still, Laurent Micheli’s 2019 Belgian feature is well-cast and well-crafted, a solid journey on familiar terrain that earns points for resisting easy sentimentality.

Some Kino Lorber reissues recently put on the Blu-ray market provide guilty-pleasure reminders that movies in less evolved times tended to emphasize the body in two very traditional ways: As girly-mag pinup cheesecake, or occasionally as grade-A beefcake. The Italians (despite their peplum interlude 60 years ago with toga-clad muscleman epics) have long specialized in the former.

A prime example is Gianfranco Angelucci’s 1981 Spanish co-production Honey, in which a wide-eyed jeune fille (Clio Goldsmith, slumming spawn of a famous German-Jewish banking family) checks into a mysterious pensione where every other guest provides her with fodder for fetish-y fantasy. It’s like Paul Bartel’s Private Parts, only this time the voyeuristic goings-on tilt away from suspense toward softcore erotica. This arty, plotless daydream was the sole narrative feature made by its writer-director, a sometime Fellini collaborator. He certainly doesn’t have that master’s touch, but this gauzy oddity is still passably diverting.

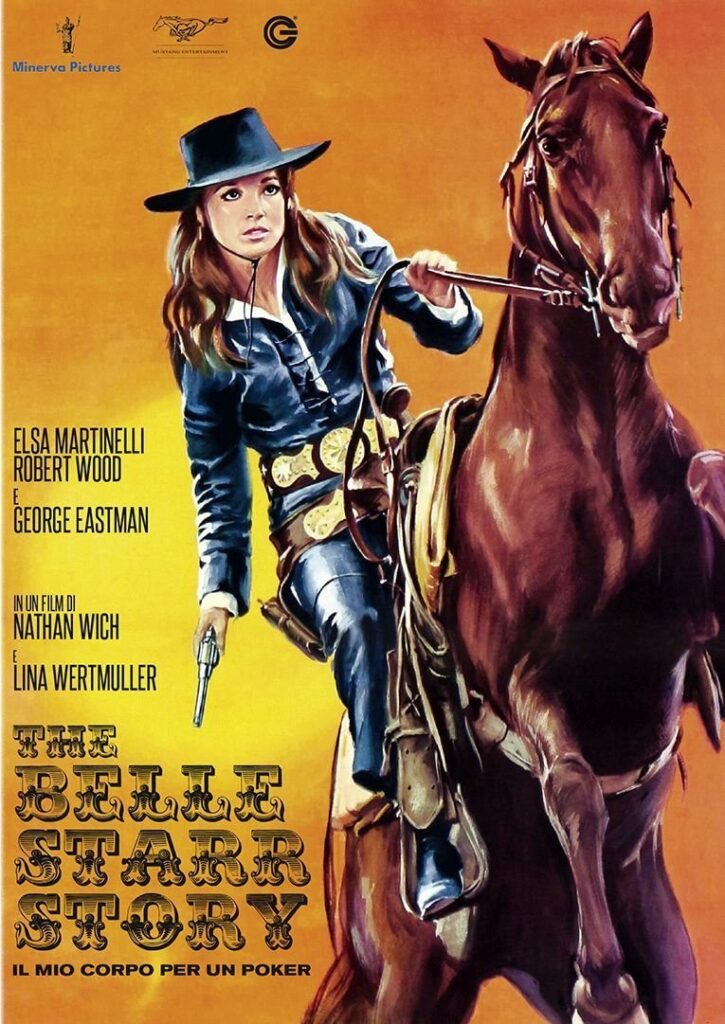

The copious nudity in Honey could only be hinted at 13 years earlier, when The Belle Starr Story was released. Among hundreds of “spaghetti westerns”—the European shoot-em-ups that briefly flourished after Sergio Leone made a star of Clint Eastwood—this has the distinction of being the only one directed by a woman. And no less than Lina Wertmuller, albeit several years before she found her own distinctive style with such international hits as Swept Away… and The Seduction of Mimi. She was, in fact, only brought on this project when the original (male) director didn’t work out. But she handles the somewhat convoluted, flashback-laden progress with sufficient lively aplomb.

Gorgeous fashion model turned actress Elsa Martinelli plays the titular real-life Wild West outlaw in this heavily fictionalized account, where she’s introduced smoking a cigar and playing poker in black leather. No man can “have” Belle—though several have violently tried—until she makes the acquaintance of Colt-carrying fellow gambler Larry Blackie, played by my favorite Italian exploitation-cinema actor George Eastman aka Luigi Montefiori. Equally dominant, smirking and trigger-happy, of course they drive each other batty in and out of bed.

Other hunks also turn up to complicate our heroine’s life (including ones played by Robert Woods and Dan Harrison aka Bruno Piergentili), and a faintly kinky air is enhanced when bad guys flog shirtless Blackie. There’s also an unusual action sequence in which a whole bunch of would-be jewel robbers stab each other to death… yet no one makes a sound, for fear of alerting the authorities just one floor below. This isn’t exactly a good movie, but it’s fun, and even in its semi-exploitative female perspective notably different from other westerns being made at the time.

Practically achieving Iggy Pop-level resistance to shirt-wearing is 1980s sports celebrity Brian Bosworth, whose NFL career was short and his movie stardom likewise—the first ended by injury, the second curtailed by the flop of a 1991 debut vehicle. But hoo man: That costly bomb, Stone Cold, turns out to be a solid-gold camp classic I had no idea I was missing out on.

“The Boz” plays an Alabama cop on suspension (because he’s just so badass!!) inexplicably drafted by the FBI to infiltrate the “Brotherhood,” a band of public-terrorizing, Mafia-connected, drug-dealing very bad hombres. Why? Because he’s “arrested more bikers than anyone in Alabama.” Uh, wouldn’t that make him extra-conspicuous to such criminals, even without his frosted blond mullet and perpetually bared pecs as identifers? Never mind. This is the kind of reality-rejecting action opus whose extravagant stunts include a motorcycle hurtling from a high-rise window so it can crash nto a helicopter that happens to be hovering outside, and which naturally explodes like a bomb on contact.

This movie has everything: Incredibly cartoonish villains (the main ones played by Lance Henriksen and William Forsythe), Rottweilers, strip clubs, a metal bar band, a pet Giant Gila monster, machine guns sneaked past guards into high-security courtrooms, plentiful gratuitous flesh displayed of both the siliconed and steroided variety. Directed by former stuntman/stunt coordinator (natch) Craig B. Baxley, it is the missing link between 1980s action excess of the Rambo-imitative ilk and the bombast soon to come from Michael Bay & co. As slick as it is trashy, originally slapped with an NC-17 rating (one can only imagine what got cut for that “R”), it makes even the then-recent macho blowhard likes of Road House and Over the Top look classy by comparison.

And even if he doesn’t “act” so much as smirk and flex, Bosworth isn’t bad—at least he’s not a block of wood like, say, Steven Seagal. While $25 million-budgeted Stone Cold proved you can go broke underestimating the intelligence of the American people (despite H.L. Menken’s saying), it belatedly deserves celebration as the Roller Boogie of yee-haw, high-octane action tastelessness.