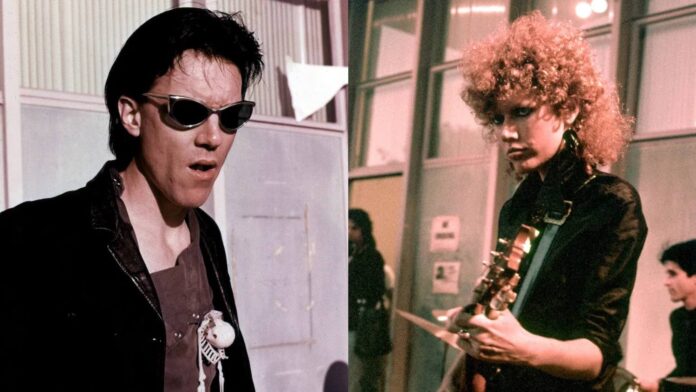

It may not be quite so prominent an occasion in the annals of popular culture as Johnny Cash playing Folsom Prison a decade earlier, but June 13, 1978 is a date of legend in punk rock history. Having apparently traveled from the East Coast for a San Francisco show that fell through, psychobilly pioneers The Cramps called on locals to orchestrate an alternative show in a hurry. Somehow that wound up being an afternoon set at the then-103-year-old California State Mental Hospital in Napa (originally called Napa Insane Asylum), with SF’s own The Mutants providing the other half of the bill. The festivities were, like much of the No. Cal. punk scene at the time, recorded in B&W by personnel from Joe Rees’ Target Video.

The Cramps footage has been available for home viewing as a cult favorite ever since, though it’s probably never looked or sounded as good as in the remastered material being presented at the Roxie this Thu/29 through July 6. (Check here for a screening schedule.) In addition to that extended, unedited material, the same treatment has been given to The Mutants’ previously unreleased set, thanks to the Punk Media Research Collection.

The Roxie program also features a newish half-hour documentary, Mike Plante and Jason Willis’ We Were There To Be There. It has input from surviving band members, hospital staff, and other witnesses (including Re/Search Publications’ V. Vale, 415 Records’ Howie Klein and Survival Research Laboratories’ Mark Pauline) recalling the experience. There’s brief discussion of the SF punk scene’s flourishing status at the time, as well as consideration of what an institution like Napa State then offered.

Patients could then commit themselves, if desired. Like many such facilities then, this Hospital was designed to be largely self-sufficient, its expansive rural acreage allowing for produce gardens and livestock. But three years later President Reagan, who had already laid siege to mental health funding as California’s governor, repealed national legislation supporting community-based care, then aggressively pushed to privatize existing asylums. Their subsequent drastic reduction in services (and self-sufficiency—all that land was mostly sold off) was without a doubt the largest single cause of the explosion in mentally ill homeless populations that’s only escalated in four decades since.

The Cramps and The Mutants: The Napa State Tapes is hence not exactly The Snake Pit or Titicut Follies—while we get a very limited sense of the overall institution, it hardly seems a dire or even high-security place. The musicians and their entourage were struck by the casualness of their welcome. Hospital administration were apparently not especially pleased about the raucous performance afterward (it’s unclear how it got approved in the first place), as several inmates chose to “escape” during its duration. But the shows themselves are chaotic in a good way—everybody is having a good time, patients are free to come up on stage and caterwaul into the mic, the music is clearly energizing.

The Mutants’ art-school New Wave pop seems made for such participatory fun, while The Cramps’ more down-and-dirty style likewise has a liberating effect. This being 1978, some of those in attendance look like hippie acid casualties, but nobody is freaking out—whether they’re pogo-ing, frugging, wandering about or just wanting to give Lux Interior a hug, the inmates are clearly enjoying themselves. It’s infectious, even if the audiovisual quality a Portapak videocam afforded at that point can only be improved so much by latterday remastering.

Members of The Mutants will be in live conversation with KXSF’s Carolyn Keddy after the first show this Thursday.

There’s also a liberating quality to the art on display in another Roxie opening this weekend, Will-o’-the-Wisp. Portuguese writer-director Joao Pedro Rodriguez is one of those rare screen talents—not unlike Wes Anderson, Quentin Dupieux, and Roy Andersson—who’ve managed to carve out an actual career path of surreal humor and narrative illogic, in an era where such eccentrically personal cinema is no longer supposed to exist. (And in which some prestigious like-minded practitioners, like David Lynch, can no longer get feature funding.) This is a concoction even more oddball than his 2016 The Ornithologist, which at least started out looking somewhat conventional.

The framework here is an elderly monarch on his deathbed in 2069, recalling his youth—mostly the stint spent as a trainee fireman, where his lofty background and physical ineptitude were a source of amusement for the precinct veterans. But Alfredo (Mauro da Costa) got a more supportive welcome from Afonso (Andre Cabal), one that soon turns erotic—then graphic, albeit via some of the most obvious penile prosthetics seen since The Brown Bunny.

Short (at just 67 minutes), episodic and wayward, Will is really just a goof, without much cumulative or lingering impact. Still, what a goof—this “musical fantasia” encompasses inspired interludes that are all entirely different from each other. There’s a station-house ensemble dance number, a fado song at a funeral, a series of tableaux vivants in which near-naked firemen playfully recreate classical artworks. The sum effect may be merely diverting rather than indelible—but still, it’s refreshingly original and frequently delightful. It opens at the Roxie Fri/30, more info here.

I’d love to know more about Rodriguez’s creative process—but presumably all that would take is looking up a print or TV interview. We’ll never get that kind of insight towards the elusive subject at the heart of Close to Vermeer. Susanne Raes’ documentary, which opens Fri/30 at the Opera Plaza and Rafael Film Center, centers around preparations for an exhibit at Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum. It will be the largest-ever for Johannes Vermeer, whose work went nearly forgotten some two hundred years after his death, before critical rediscovery beginning in the 19th century began raising him to the current level of international reverence.

Yet almost nothing is known about the artist, save that he lived from 1632 to 1675, primarily made his living as an art dealer rather than a painter, and set nearly all his own canvases within two rooms of a house in Delft. Those domestic scenes would be interesting enough for their peeks at middle-class Dutch life. They’re made revelatory by compositions, detail, use and portrayal of light etc. that remain a mystery—not only “ahead of their time,” but their technique still puzzled over by experts.

We don’t even know how many Vermeers survive, since several paintings attributed to him continue to be debated in an era when X-rays and other modern technologies have made an artwork’s backstory easier to uncover. He left behind no letters or diaries, so one can only guess if he had apprentices or assistants who might partly or wholly be responsible for a “Vermeer” that somehow isn’t quite.

This engagingly low-key inquiry globe-trots to extract wisdom from conservators, dealers, collectors, restorationists, curators, and others obsessed with this artist’s legacy. We glimpse the negotiations required to pry loose a Vermeer on loan from an institution reluctant to leave their physical possession. We see analysts determine that a particular image isn’t (or isn’t entirely) the master’s—for reasons that seem perfectly obvious to them, but can’t fully shake the personal convictions of professional superfans. (One admits that when he first saw a Vermeer many years ago, he was so moved that he fainted.)

While you may know what you think you know from the imaginative fiction of Girl With a Pearl Earring—either the novel or movie inspired by that most-famous painting—Close argues that sometimes not knowing can be art’s most compelling quality of all.