This Wednesday brings the culmination of a fabled screen action star’s career. No, we don’t mean Tom Cruise in the latest interchangeable entry to a franchise based on an old TV series (although indeed, Mission Impossible: Dead Reckoning Part One also arrives June 12.) But his movies owe everything to the template established a century or so ago by Douglas Fairbanks, who also “did his own stunts” or at least said so. That original rascally athlete-hero kicks off the 26th San Francisco Silent Film Festival at the 101-year-old Castro Theater with 1929’s The Iron Mask, an Alexandre Dumas mashup that was a sequel of sorts to the star’s Three Musketeers eight years earlier.

It was a swan song in many respects: “Talking pictures” were already in full swing, so Fairbanks knew this would be his last silent. The new medium’s as-yet-onerous technical requirements and his own advancing age (he was pushing 50) meant an end to the extravagant, ebulliently physical spectacles he’d been making for the last decade, playing Robin Hood, Zorro, and the Thief of Bagdad. Those movies duly established the rollercoaster-ride conventions of such populist blockbusters for keeps, as still demonstrated by Indiana Jones, Cruise, and even comic-book movies—and they did it without computerized FX.

Directed by Allan Dwan (whose half-century career would stretch from Fairbanks and Gloria Swanson through Shirley Temple to film noir), Mask bowed to fashion by including a couple sound sequences. But it was mostly a summational fond-farewell to past glories, one overt enough to include something no other showcase for Fairbanks had allowed: His character (D’Artagnan of course) actually dies. The touch of melancholy, while alleviated by a cheerful fantasy epilogue, was prescient. This great star of the silent era dimmed considerably in the “talkies,” his legendary marriage to Mary Pickford collapsing, and the man himself dead of a heart attack at age 56 in 1939.

This year’s Silent Fest is bookended by that starry mainstream start and the closing night selection on Sun/16 of The Merry Widow, a 1925 vehicle for newly minted studio MGM’s leading lights Mae Murray and John Gilbert, based on the popular operetta. Its risque Ruritanian romance was right up the alley of director Erich von Stroheim—but so was a reputation for perfectionism and cost overruns that had kept his prior hits from turning much profit despite their high grosses. Ergo executive Irving Thalberg watched the troublesome “genius” like a hawk, keeping things on schedule and within budget.

Von Stroheim resented that oversight so much, he never worked under such circumstances again. Which is a real pity: Such obstinacy would soon end his directorial career entirely. And The Merry Widow was not only the most successful but also perhaps most enjoyable movie he ever made. It’s a lush, stylish, witty divertissement that’s often very funny, and manages to reign in the usual diva histrionics of future Norma Desmond model Murray (whom von Stroheim loathed, and vice versa).

The five-day festival is packed with mostly lower-profile but rewarding rediscoveries, most in new restorations, some films that for long years were thought lost. All will be accompanied at the Castro by iive musicians, from organ soloists to various ensembles, often playing specially commissioned scores.

Here are some highlights in the program (go here for further details, plus schedule and ticket info):

Famous Directors Before They Were Famous: Ford, Ozu

Help us save local journalism!

Every tax-deductible donation helps us grow to cover the issues that mean the most to our community. Become a 48 Hills Hero and support the only daily progressive news source in the Bay Area.

While a few directorial names such as D.W. Griffith, de Mille, and von Stroheim were selling points to audiences in the silent era, for the most part their brethren labored under-radar. A couple talents who would become legendary in decades to come have early works showcased in SFSFF this year. John Ford had already had a big hit with the prior year’s western epic The Iron Horse when he made 1925’s Kentucky Pride. It’s a comparatively minor effort, but a novel one: This “autobiographical” portrait of a champion thoroughbred racehorse is narrated (via intertitles, of course) by the horse itself.

Lesser-known even amongst the early works of prolific Japanese master Yasujiro Ozu (whose later efforts include world classics like Tokyo Story and Late Spring) is 1930’s Walk Cheerfully, a seriocomic tale of some small-time urban gangster types. Their highly Westernized ways are most amusingly demonstrated in elaborate shared body language that’s like “secret handshakes” taken to choreographic extremes. But when Kenji (Minoru Takada) decides to go legit for love of traditionally kimono-clad country woman Yasue (Hiroko Kawasaki), his erstwhile friends don’t take it well. Unexpectedly touching, this is one of the best films in the program.

Comedy, From Slapstick to Sexy to Soviet

Even when it was otherwise dismissed as hopelessly old-fashioned, silent cinema was considered a golden age for screen comedy, particularly of the slapstick sort. Two shorts programs mine that deep vein: One collects vehicles made by Harold Lloyd’s production company for Edward Everett Horton, who is much better remembered for his long sound era career as a favorite character actor (and distinctive voice artist, notably as narrator for cartoons like The Bullwinkle Show).

Another brings together early teamings of Laurel & Hardy, including prison-break tale The Second 100 Years and Battle of the Century, famous for its ginormous pie fight. Arguably funnier than either is 1928’s Flying Elephants, in which they are fur-clad men of the Stone Age seeking mates. Then there’s the fence-straddling of Three Ages: Buster Keaton’s first starring feature, albeit one made in distinct segments (set in caveman, Roman, and modern times) that could be released separately in case it turned out 1923 audiences only wanted to see him in shorts. (This turned out to be a needless worry.)

Going for laughs in other ways is Up in Mabel’s Room (1926), in which the ill-fated Marie Prevost is a flighty flapper who’ll stop at nothing to win back the ex-husband (Harrison Ford… yes, there was a prior one) she divorced over a misunderstanding. It’s a racy boudoir farce with see-through black lingerie as a major plot device. There’s no such capitalist decadence on display in the 1931 Ukrainian Pigs Will Be Pigs. This ensemble comedy flaunts a barbed satirical distrust towards public institutions, as missing guinea pigs, much-needed grain, quarreling peasants, bull-headed bureaucrats, et al. create havoc along a tardy train’s route.

Rex Beach, Forgotten Beach-Read Titan

An Olympic water polo player and failed Alaska Gold Rush prospector, Beach found great popularity—if little critical acclaim—writing page-turners of manly action fiction. Many were adapted for the screen, including two entertaining melodramas in this year’s festival. Flowing Gold (1924) follows the travails of the Briskow family in Texas, who go from nearly losing the farm to sudden wealth via oil strike. Their nouveau riche status attracts predators, including a self-appointed adviser (the excellent Milton Sills) who turns out to be redeemable after all. There are very funny scenes as the Briskows go Beverly Hillbillies, plus a climax that’s all fire and flood. This film was remade in 1940 with John Garfield and the tragic Frances Farmer.

A more atypical story for Beach was Padlocked (1926), in that it was female-centered and about urbane “flaming youth.” A tycoon (Noah Beery Sr.) is such a pious, moralizing pill that he alienates his daughter (Lois Moran), who runs away and becomes a cabaret dance star. In retaliation, he sends her to a juvenile reformatory. But he gets his just reward: His second wife (following the one he accidentally killed) turns out to be a shameless golddigger with an entire family of tacky parasites to torment him. Directed by the aforementioned Dwan, this is another juicy story with a lot of satirical humor that particularly enjoys pricking the pretensions of religious hypocrisy.

German Expressionism and Beyond: Fantastic Visions

The vividly abstract design trends that first struck screen audiences via 1920’s Cabinet of Dr. Caligari quickly influenced filmmakers abroad, while continuing to evolve in Germany. A fairly late example there was A Daughter of Destiny, whose writer-director Henrik Galeen was considered a major force in the movement. It has Metropolis’ Brigitte Helm as a different sort of human “golem”: A young woman whose amorality is the apparent result of her unnatural origin as a mad scientist’s test-tube baby, then a very futuristic concept. It eventually bogs down in conventional melodrama, but the stylish production shows German studio craftsmanship at its peak.

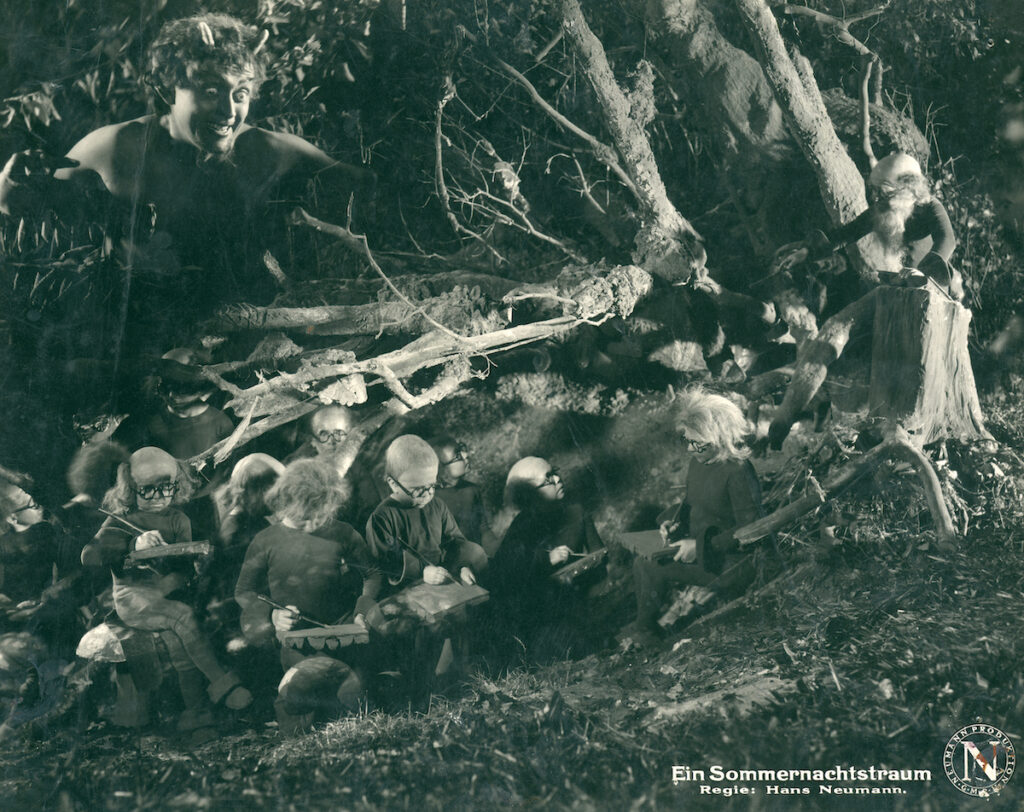

In a different way, so does Hans Neumann’s long-lost 1925 version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, a gauzy fantasia whose scenes in the enchanted forest of fairies and elves make considerable use of double-exposure. This “merry carnival drama” is pretty loose Shakespeare (“Holy Zeus! It’s a busy night in Athens today!” one intertitle reads), but it does give good eye candy—some awfully similar to the sights Max Reinhardt would conjure in his all-star flop version for Warner Brothers a decade later.

Such European talent was eagerly sought by Hollywood. Among those who took the bait was art director, animator, and macabre horror classic Waxworks creator Paul Leni. Landing at Universal, he immediately made a splash adapting the full paintbox of Expressionist tricks to populist ends in 1927’s The Cat and the Canary. This classic “old darke house” meller—involving trap doors, hidden passageways, clutching-hand ghouls, and the reading of a wealthy recluse’s will—balanced jump scares with comedy to trend-setting effect; it remains a riot of playful visual invention.

Poetic Realism, French and Czech

Two of the stronger dramas revived this year anticipate neo-realism in naturalistically detailed chronicles of hapless protagonists ground under by forces beyond their control. Based on an Anatole France novel, Jacques Feyder’s Crainquebille finds an old, simple Parisian produce peddler (Maurice de Feraudy) thrown into jail after a needless dispute with a bullying gendarme. Once out, he’s shunned by customers, leading to the bottle and homelessness.

Another solitary soul is the Organist at St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague. Played by songwriter and theater director Karel Hasler, he’s a victim of cruel fate whose downward path is briefly brightened by a friend’s orphaned daughter (Suzanne Marwille). As in Crainquebille, last-minute salvation—as well as exceptionally graceful filmmaking—comes to the rescue. There was no such happy ending for this 1929 release’s leading participants offscreen, however: As a leading patriotic figure, Hasler was arrested by Nazis and killed in a concentration camp 12 years later, while ailing director Martin Fric committed suicide the day Soviet tanks invaded Czechoslovakia in 1968.

There’s much more in the Silent Fest, including a vehicle (The Dragon Painter) for Sessue Hayakawa, the first Asian man to achieve Hollywood heartthrob status; dramas shot in rural Appalachia (Stark Love) and on the Amalfi Coast (Voglio a Tte!); disaster flick The Johnstown Flood, whose special-effects-aden climax was so exciting, the footage got re-used in several subsequent features; Phantom of the Opera screamer Mary Philbin playing dual roles in the treacly Stella Maris; and Man and Wife, a 1924 tearjerker in which runaway farmgirl Norma Shearer’s discontent (“I’m tired of bringing up the cows! I want life! Happiness!”) triggers a whopping pantsload of melodramatic contrivance.

That last film is rather oddly paired with what may well be the revelation of the entire festival: The Great Love of a Little Dancer, a 21-minute German marionette novelty (also from 1924) that’s like a George Grosz drawing come to life, or a Lon Chaney movie in wooden miniature. Its bizarre carnival-set adult nightmare is very twisted and surreal, to a degree where one wonders just who the intended audience was. But it’s hard to imagine this obscurity did not somehow get seen by Jan Svankmajer, or even Tim Burton—the bug-eyed villain is rather a ringer for figures in the latter’s animated films.

The 26th San Francisco Silent Film Festival runs Wed/12-Sun/16 at the Castro Theatre. More info here.