Mayor London Breed personally ordered illegal sweeps of homeless encampments and the city regularly harassed unhoused people, destroyed their belongings, and violated their Constitutional rights, legal document filed today allege.

The documents, part of a lawsuit filed by the Coalition on Homelessness, include declarations by former city employees who say Breed and other officials in her administration were more concerned about appearances than about following the city’s own policies on the unhoused.

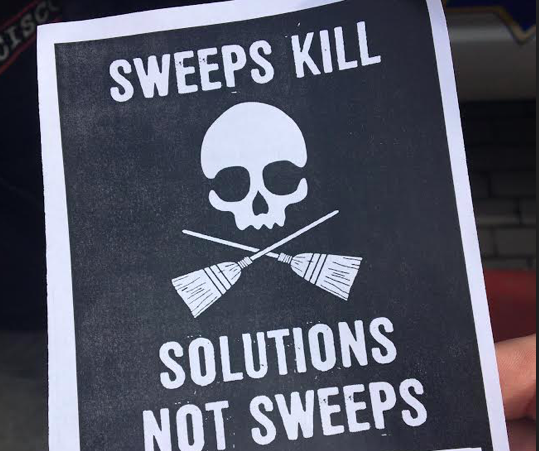

According to the declarations, officials at the Department of Public Works said they were “at war” with the unhoused.

From a declaration by Keki Marshall, former director of outreach and temporary shelter at the Department of Homelessness:

Mayor Breed sent to staff to remove unhoused people from sight. She would order us to displace unhoused people by a certain date and time just because they were in the vicinity of her planned schedule for the day. Mayor Breed ordered us to carry out sweeps because she did not want to be seen near unhoused people while she was at lunch, at the gym, at fundraisers, or at meetings on public business.

More:

Specifically, Mayor Breed would text [DOH leaders] Jeff Kositsky, Sam Dodge, or the chief of police directing them to immediately remove certain individuals from specific areas. The clear mandate from the Mayor was that the unhoused should not be visible in public, even if they had nowhere else to go. HSOC would race to respond, putting other planned and organized sweeps on hold. We would hold a special HSOC meeting to redirect resources to the areas Mayor Breed had identified for that day. In other words, rather than allocate services by need, political theater would dictate the services.

The lawsuit alleges that the city is violating federal law by criminalizing and removing homeless people from city streets when there is nowhere for them to go.

A key issue in the case: When the city sends crews to remove encampments, does it offer all the residents a safe, acceptable shelter alternative?

The declarations filed in the case provide strong evidence that the city, despite policy statements to the contrary, routinely breaks up encampments, destroys the property of unhoused people—and doesn’t or can’t provide any alternative housing.

The suit seeks an injunction prohibiting further sweeps until adequate housing is available.

In its response, the city cites its written policy:

San Francisco’s policies ensure a person experiencing homelessness is asked to leave an encampment only after the person has received an offer of shelter and declined it. And San Francisco’s policies specify that it disposes of an item only upon determining it is trash, garbage, debris, broken furniture, a discarded appliance, or presents an immediate health or safety risk such as hazardous sharps, chemicals, items soiled by infectious or hazardous materials, and items infested by rodents or insects, or is intermingled with refuse. Other items are bagged and tagged and stored 90 days at a central warehouse.

But while that may be official policy, it’s not the reality on the ground, according to extensive evidence produced in the suit:

Rather than addressing the reality of the City’s rampant misconduct, Defendants baselessly reject Plaintiffs’ dozens of supporting declarations and years of underlying data while continuing to terrorize unhoused communities with impunity.

Defendants provide no evidence to disprove that San Francisco has insufficient shelter and housing for all its unhoused residents and is at least thousands of temporary shelter beds short.

Defendants do not respond to the extensive public records that show the City has threatened unhoused individuals with criminal enforcement and has cited or arrested unhoused San Francisco residents purely for sleeping or lodging in public thousands of times over the past several years— both at [Healthy Streets Operation Center] encampment resolutions and when SFPD is dispatched independently to respond to homelessness complaints.

From a declaration by Andrinna Malone, who spent 18 years working at DPW:

Throughout my entire career at DPW—and especially in recent years—I personally witnessed many incidents where DPW conducted sweeps without posting a written notice in advance of a homelessness sweep. If there was a lot going on—like media coverage or other political pressure—then DPW would post a notice before going to a site. Additionally, if unhoused people at the location were political, meaning they knew their rights, we would try to post a notice. On a daily basis, though, there was usually no warning that we would be coming.

Although DPW employees are required to bag and tag items that they take from unhoused individuals, this rule is rarely followed. I have seen many instances where DPW personnel made no effort at all to bag and tag property and would take unhoused people’s belongings straight to the dump.

Among those belongings were essentially medications, wheelchairs, and crutches.

That confirms consistent reports we’ve seen about the failure of DPW to preserve the belonging of people displaced in sweeps.

By law, and under city policy, unhoused people can’t be swept from the streets unless the city offers them a place to go. But the evidence presented in the case makes clear that the city simply doesn’t have enough shelter beds or permanent supportive housing for everyone who is living on the streets—not even close.

So city officials pretend that homeless people have “refused” shelter, which justifies the sweeps.

From Marshall’s sworn declaration:

We gathered at HSOC the week after the first operation to prepare our report for the weekly HSOC meeting. This is when I discovered that Mr. Dodge intended to report to HSOC leadership that, of the 20 individuals we had encountered, practically all of them had refused shelter. But the HOT team would often only be able to tell unhoused individuals that the police were coming without conducting any coordinated entry assessment that would constitute a shelter offer. Mr. Dodge’s tracker logged all of these interactions as shelter refusals, but this was plainly inaccurate and a blatant attempt to work around the City’s stated requirements for enforcement.

But since there was not ever enough shelter to offer individuals at these HSOC operations, the HOT team was typically only able to warn unhoused individuals that the police were coming to force them to move— or the HOT team would advise unhoused people to leave themselves.

The picture that is emerging from the lawsuit is that even Breed Administration staffers who care about and want to help unhoused people have no choice: The mayor wants the streets cleared of homeless encampments, and everyone who works for her is forced to go along.

From the declaration:

The DPW management called the work we did a war. They pitted us against them—them being the unhoused individuals we interacted with daily. This really bothered me. I never understood why department leadership would call it a war, when we were not supposed to be fighting unhoused people but rather helping them.

The case is slated for a hearing Dec. 22 before Federal Judge Donna Ryu. As it goes forward, more and more data about how the city treats its least fortunate is going to become part of the public record.

.