Read part 2 of Lucas’ photo-essay here.

A wind-swept bluff overlooking the Pacific Ocean. A grotto of impossibly luxe mansions. An overgrown canyon carved by a modest creek, adjoining a district made isolated by the highway on one side and the steep hills on the other. A working-class neighborhood on the edge, both geographically and socially.

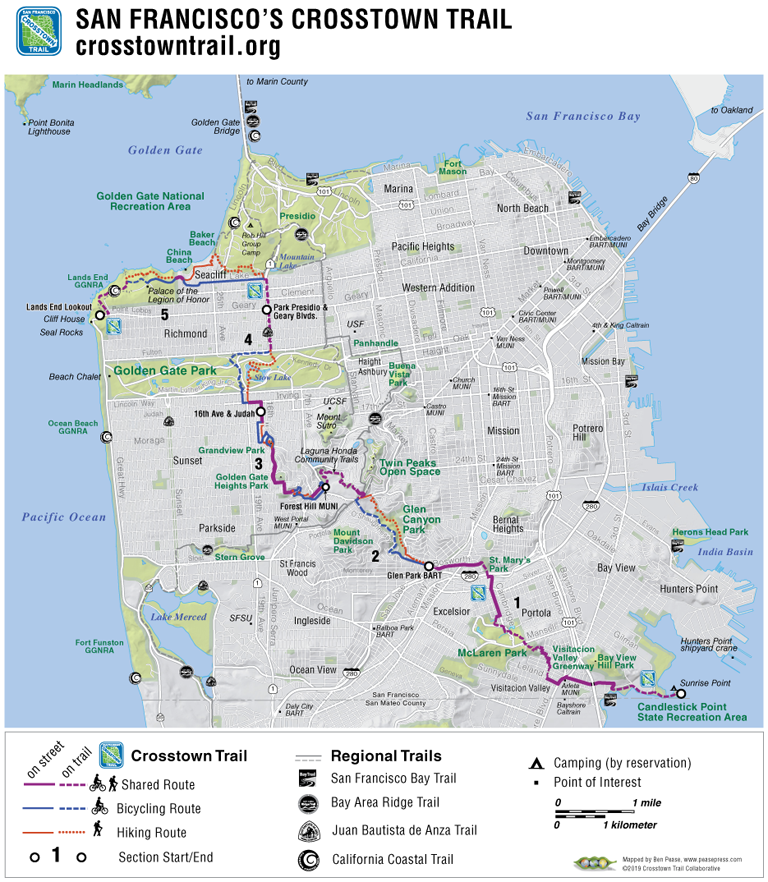

Somewhat implausibly, all of this exists squeezed into an area of less than 50 square miles, in that most implausible of cities, built over hills on a chilly, foggy peninsula: San Francisco. And it can all be seen on the epic, 16.7-mile journey that is the San Francisco Crosstown Trail.

The Trail, which officially opened in June of last year, is a continuous network of parkland, dirt paths, and sidewalks, connecting the southeastern corner of the city, Candlestick Point, to the northwestern, Lands End. But the Trail is more than a series of stunning views and neighborly walks. From end to end, the Crosstown Trail reveals much about San Francisco.

The Crosstown Trail reveals, in subtle fashion, the ills facing the city. Starting the trail from the southeast, the first neighborhood one passes through is Visitacion Valley, rare in San Francisco for being virtually untouched by gentrification. The neighborhood has been outpaced by the rest of the city in many ways, but doesn’t feel “depressed” or “neglected”—Leland Avenue, which lies along the trail on the way to McLaren Park, is lined with mom-and-pop storefronts. In Visitacion Valley, one can see San Francisco as it once was, and can still be: a vibrant home for the working class and people of color.

One climbs through McLaren Park, the third largest park in the city, and then down Cambridge Street. Here, a luxury condo development hints at the housing crisis that looms over the city. The Portola development is anticipating prices starting at “the low $1 millions.” A footbridge brings you across I-280, crossing both a literal and metaphorical threshold. Across the bridge is a quiet neighborhood, with low, detached houses with neat lawns. It has a suburban, “anywhere in America” feel, contradicting the typical idea of San Francisco architecture. At the aptly-named Grandview Park, a panorama unfolds, and the mesmerizing beauty that has attracted generations of Americans smashes you over the head. A realization: the city’s unique architecture is both a blessing and a curse; it bestows the city with its beauty, but also leaves it starved for space.

Seeing the massive shifts in the layout of the city, from the humble Visitacion Valley to the sprawling mansions at Sea Cliff, has a strangely dissociating feel. It’s not an unwarranted feeling: 50 years after its official end, the effects of redlining are still obvious in San Francisco. A “residential security map” from 1937 shows the neighborhoods on the southeast portion of the Trail bathed in red, “hazardous.” At the time, the boundary between the “D-grade” and “C-grade” neighborhoods was Mission Street. Today, that boundary roughly defines the gentrification that slowly creeps across the city.