The works of Carlos Villa, the visionary Filipino artist, instructor, and community organizer born in San Francisco’s Tenderloin, are on view at two major San Francisco institutions. Villa is the first Filipino American artist to have a major museum retrospective.

The San Francisco Arts Commission is hosting “Roots and Reinvention” in its new gallery space on the first floor of the War Memorial Opera House through Sat/3. The three-room exhibit “Worlds in Collision” at the Asian Art Museum focuses on Villa’s works, mostly from the 1980s-’90s, and is up through October 24.

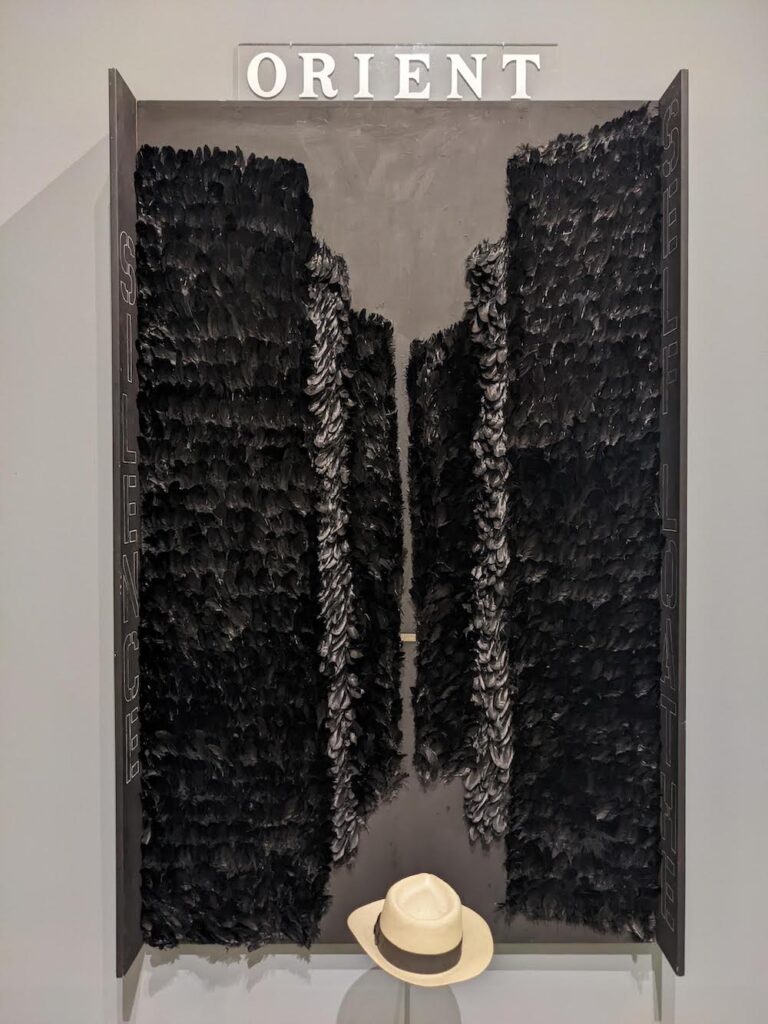

Villa’s unusual body of work includes large-scale mixed-media productions made from uncommon materials such as feathers, chicken bones, and human blood. He painted using his own face as a brush, and constructed talismanic figures such as wings, snakes, masks.

His forms deal with a number of inter-related concepts: ritual, ceremony, the evocation of ancestors, and the corresponding catharsis and self-discovery that arises from all the above.

At the San Francisco Art Institute, where he was a student and longtime member of the faculty, Villa created a multicultural arts curriculum program—regarded by many as the first of its kind in arts education—called “Worlds in Collision” (from which the Asian Art Museum exhibition takes its title), beginning in 1976.

Villa created inclusive curriculums and symposiums associated with “Worlds in Collision,” such as “Rehistoricizing Abstract Expressionism in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1950s–1960s” at the Luggage Gallery (a project highlighting the work of lesser-known women artists and artists of color) until his death in 2013.

“Back in the sixties I started with my own art,” Villa said in a 1995 interview with the Smithsonian Archives of American Art. “I started trying to recuperate some of these things. And not to do a Filipino art but to do an art of my own. To do a visual kind of excavation of things to bring me closer to my own root—whatever that root was, being Filipino American.”

Born in 1936 and raised in an apartment on Geary Street between Polk and Larkin, Villa was first introduced to art through an older cousin, abstract artist Leo Valledor. It was Valledor who encouraged Villa’s enrollment in SFAI (then called the California School of Fine Arts) and helped organize Villa’s first gallery show in 1958. Villa spent time in New York making minimalist art before returning to San Francisco. Here, he befriended classmates and other working artists such as Joan Brown and Bruce Connor. In 1969, he took a position as an instructor at the Art Institute, where he would work as a faculty member in the painting department for the next 40 years.

Villa saw his Filipino community as having been shaped by two major policies that deeply impacted San Francisco history. One was federal and state anti-immigrant legislation (such as the 1875 Page Act, the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, and 1913 California Alien Land Law), laws that limited the number of Filipino immigrants, particularly women, preventing the development of the Filipino community. Decades later, 1940s redevelopment programs bulldozed areas that were home to many of the city’s Filipino families, such as the Fillmore, Western Addition, South of Market, and the Chinatown-adjacent Manilatown.

The artist later witnessed the militant-but-failed resistance to the eviction of the aged Filipino residents from the I-Hotel, the place where his father once told him he could go if he ever felt lonely and in need of connection to his Filipino culture.

“I believe that art and life have to interface,” Villa told the Smithsonian. “Otherwise, art doesn’t make any difference. I mean, it’s just another object, or it’s just another idea. But when it becomes part of life then it becomes cherished, it becomes valued.”

He was inspired by much of the community organizing taking place at the time, including the growing Chicano community mural movement in the Mission District and the Third World Liberation Movement. The latter, Bay-Area-centered political consciousness was originated by the multi-racial coalition of students who fought for the creation of an ethnic studies department at San Francisco City College (which became the first such department in the nation) and San Francisco State University.

Villa cataloged his experience of growing up Filipino in San Francisco by integrating family history, geography, and cultural signs and signifiers into his work.

“He was from the neighborhood,” San Francisco poet Tony Robles told 48hills. Robles’ uncle Al collaborated with Villa on a number of art and cultural projects. “He grew up seeing and hearing the manongs [the first generation of Filipino men to immigrate to the United States], and the voices and smells of their lives stayed in his skin. He was a man of contradictions and complexity whose legacy provides as many questions as answers.”

Indeed, Villa’s work seems to successfully grasp something otherwise ineffable. “My Father Walking Down Kearny Street for the First Time” (1993), which is on display at the San Francisco Art Commission, is a mixed-media piece registering somewhere between a surrealist painting, a shadow, and bird of prey. The piece captures the gravity of the immigrant’s arrival, the first walk into the heart of the neighborhood where he will spend the rest of his life.

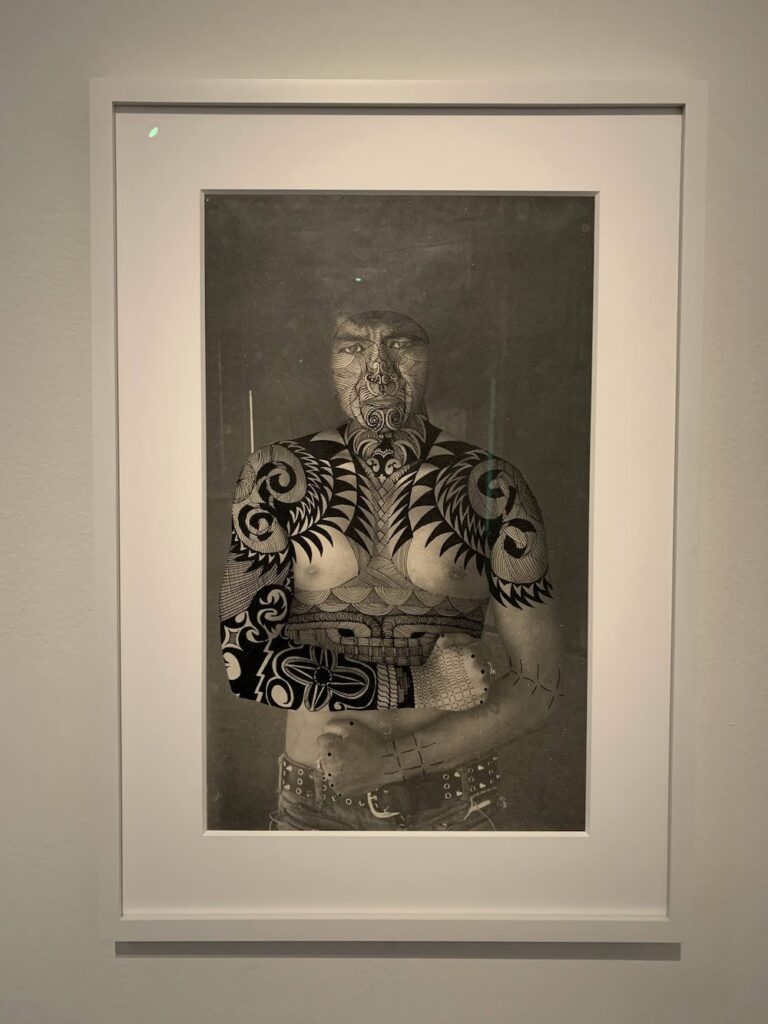

Another key piece is “Tat2” (1971), a commanding self portrait photograph of the artist being shown at the Asian Art Museum that is overlaid with pen and ink drawings resembling tattoos. A version of this work called “XXXTat2” was painted in the form of a mural last year by one of Villa’s former students, Mario Ayala, in the Tenderloin at 350 Turk Street.

Villa’s work later became even more expansive, zooming out through time and space, resulting in the large-scale multimedia pieces for which he is known. These works draw connections between the ancient land masses of Oceana and the African continent. Here, Villa goes deeper into his ancestral inquiry, past the colonial powers of the United States and Spain, which, in his chosen scale, are relatively-recent arrivals.

His contributions to San Francisco’s art world, to the creation of the category of “Filipino art,” and to the field of art education, are enormous. It was high time for a large retrospective of Villa’s work such as the one that was initially planned to span over three significant San Francisco sites.

But the would-be retrospective triptych of Villa’s life work is missing a major, and majorly symbolic, panel. A third exhibition was planned for the Art Institute, timed to celebrate the institution’s 150-year anniversary. The exhibit, though it continues to be advertised, was never installed. Art Hazelwood, union steward for the art institute’s adjunct faculty, told 48hills that the institute’s trustees fired instructors and curators at the end of July and there are no plans for exhibits, including Villa’s, to go forward.

Though the remaining two exhibits stand on their own, it’s hard to ignore this missing component, an indicator that something is seriously wrong with San Francisco’s art world. Villa’s hometown retrospective is occurring during the dissolution of one of the oldest and most-highly-regarded art schools in the country, the place where Villa dedicated four decades of his life to teaching and mentoring generations of students.

The closing of the San Francisco Art Institute, its gorgeous campus, open studios, and historic Diego Rivera mural to young students and to the general public is a loss for San Francisco and to the legacy of Villa. If San Francisco truly loves its artists, it must honor their commitment to art.

Carlos Villa was on to something, and the questions raised by his life’s work as an artist and educator are far from settled. Villa’s art goes beyond the personal and beyond the present—it is historical, it is futuristic, it evokes ancestors, and luckily for us, leaves traces for future generations.

CARLOS VILLA: ROOTS AND REINVENTION. Runs through Sat/3. San Francisco Arts Commission Galleries. More info here.

CARLOS VILLA: WORLDS IN COLLISION. Runs through October 24. Asian Art Museum, SF. More info here.