UPDATE: Due to flooding, the “Dale is Dead” program at the Lab has been postponed to a future date. Stay tuned!

The new year is still young, and it makes sense that some significant local film events this week should having a looking-backward focus—though for the most part it’s considerably further back than last year. 2022 was, however, when San Francisco lost Dale Hoyt, who by his own account “came of age” in the early 1980s as a student in the San Francisco Art Institute’s newly formed performance-video department, then taught there for years afterward.

He was a video artist whose work reflected the tone and aesthetics of the peak SF punk scene he was very much a part of, as well as a curator (including a brief staff stint at NYC’s famed The Kitchen), writer, music-video director, and prolific practitioner in other media. A longtime SRO tenant at the El Dorado Hotel, he succumbed to cancer while still in the middle of programming the ’80s retrospective Punk/Performance in the ‘Loin, which gallery exhibit opened at the nearby Tenderloin Museum last May, just weeks after his death at age 61. Its off-site elements included a reunion concert at Great American Music Hall by original SF punk/New Wave faves Flipper, The Mutants, and Longshoremen.

San Francisco Cinematheque further commemorates this “crazy, brilliant” artist’s career this week with several programs, all curated by former Pacific Film Archive video curator Steve Seid. The on-site one, Thurs/12 at The Lab, is Dale Is Dead (more info here). It pulls together nine video works by Hoyt himself, from 1981’s pastiche of camp-melodramatic despair Your World Dies Screaming through a couple Reagan era magnum opuses (Over My Dead Body, The Complete Anne Frank—latter features Tuxedomoon’s Winston Tong as a Nazi), past a dormant period to some 21st-century efforts.

Available from that day through January 31 is the online program Chaos Theory (more info here), a survey of frequently prankish, performance-arty videos from Hoyt’s local contemporaries and frequent collaborators from four decades ago, including Andrew Heustis, Marshall Weber, Cecilia Doughtery, Paula Levine, Azian Nurudin and Leslie Singer.

Finally, there’s the publication of zine An Urgent S.O.S. Through a Sea of Static: Writings by Dale Hoyt and Natalie Welch (more info here). Welch was Hoyt’s occasional print pseudonym, one he used to playfully critique fellow video artists’ “simultaneously refreshing and exasperating” work—a description that could well have served for his own—including a group show he curated himself. Other essays address XXX erotica in the VHS age (he’s unimpressed), and the then-new (in 1985) phenomenon of MTV—which he decried for, among other things, its “despicable depiction of women” as “either succubi or dingbats.”

Though his works were shown and collected in some high-profile US and overseas institutions, Hoyt remained to the end proudly resistant towards any artistic complacency or conformism. A BAMPFA series ending this week showcases a stubbornly avant-garde artist who rebelled within the Japanese commercial film mainstream and was punished for it, finally emerging triumphant with his sensibility intact. Before the holidays, Elegy to Seijun Suzuki (more info here) showed features from the titular late maverick’s early career, including 1966’s classic yakuza thriller Tokyo Drifter. But by the time he completed Branded to Kill the next year, Suzuki’s escalating experimentation with narrative and style was viewed as “incomprehensible” by his studio, Nikkatsu. They terminated his contract, and he sued—successfully, albeit at the cost of being blackballed throughout the industry for a decade.

The last two films in the Berkeley series, playing this weekend, show his reemergence after that forced sabbatical, which had made him something of a cult hero amongst forward-thinking Japanese cinephiles. 1977’s A Tale of Sorrow and Sadness (Fri/13, more info here) is a satire of advertising manipulation and empty celebrity, chronicling the rise of a female golf pro whom a sleazy promoter sculpts into a media star. Eventually it becomes a sort of All About Eve revamp, with a vindictive female fan blackmailing her way into the heroine’s life. Not one of Suzuki’s best, negotiating a somewhat wobbly path between melodramatic sexploitation and critique, it still bears the distinguishing mark of his idiosyncrasies.

Much more assured is 1981’s Kagero-za, (Sun/15, more info here) which followed in the vein of the prior year’s comeback hit Zigeunerweisen as a period ghost story/romance—though typically for Suzuki, even that supernatural premise is clouded by hall-of-mirrors storytelling. Its central “mystery woman” conflict keeps being acted out in different ways, including (at one point) as a children’s stage play. Never mind logic: “Who talks of realism here?” says one character, before cackling madly. More key to the film’s long, serpentine, surreal effect is its frequently stunning visual schemata, which the director would extend even further in such later works as Pistol Opera (2001) and Princess Raccoon (2005). Ill health nudged him into retirement eleven years before his 2017 death at age 93. Both Berkeley screenings will be of imported 35mm prints.

Starting this Thurs/12 and running through February 25 is a new BAMPFA series, The Cinema of the Absurd: Eastern European Film, 1958-89 (more info here). It encompasses movies both from the region’s fabled “New Wave” flowering in the 1960s, and from the more restrictive period following the Soviet crackdown on “Prague Spring” protests in 1968. Before and after, absurdism remained one way to tiptoe around the government censors, masking political critique in seemingly nonsensical storylines and humor—though that underlying intent may seem fairly obvious to us now.

The series does encompass a couple early shorts by subsequently famous directors: Roman Polanski’s Two Men and a Wardrobe, and animator Jan Svankmajer’s live-action The Garden. But otherwise it avoids the familiar—such as Milos Forman’s The Fireman’s Ball or Vera Chytilova’s Daisies, which recently came in at #28 on Sight and Sound’s “Greatest Films of All Time” poll—in favor of lesser-known works. This is all to the good, as you can never dig too deep into the celluloid riches of a period that was liberating for cinema almost everywhere, quite remarkably so in nations of the Eastern Bloc. (Except Russia itself, where some fine films were made to be sure, but censorious control didn’t relax much until later.)

A particular revelation is Lucian Pintilie’s 1968 The Reenactment (playing Sun/Feb. 19 more info here), which is not obscure in Romania—local critics once voted it that nation’s best film ever—but remains little-seen abroad. At once a simple narrative and a subversion of that narrative, even of storytelling and cinematic conventions themselves, it ostensibly focuses on the titular event one afternoon at a ramshackle lakeside resort area. There, two youths have been brought by the authorities to reenact a drunken brawl they had for some sort of cautionary “educational” film.

But as the hapless duo’s minor scuffle is reprised in increasingly warped form, they (and we) realize they are just pawns in a system that will surely crush them to “save” them. What starts out as a loose, anecdotal, bucolic comedy of the Forman type gradually acquires layer upon layer of complex indictment. That was not lost on the real-life authorities, who shelved The Reenactment upon its completion, allowed it briefly shown, then pulled it from Cannes and banned it entirely. (Stalled for some years thereafter, Pintille’s career would eventually revive itself, particularly with 1992’s immediately post-Ceausescu The Oak.)

Very much a product of its production moment in terms of Godardian fourth-wall breakings and quasi-verite touches, this is one of the most artistically successful narrative experiments on film ever made. Also exceptional is Peter Bacso’s 1969 Hungarian The Witness (Fri/27, more info here), whose equally corrosive satire of an ineptly, overzealously policed society likewise went unseen by the public for years.

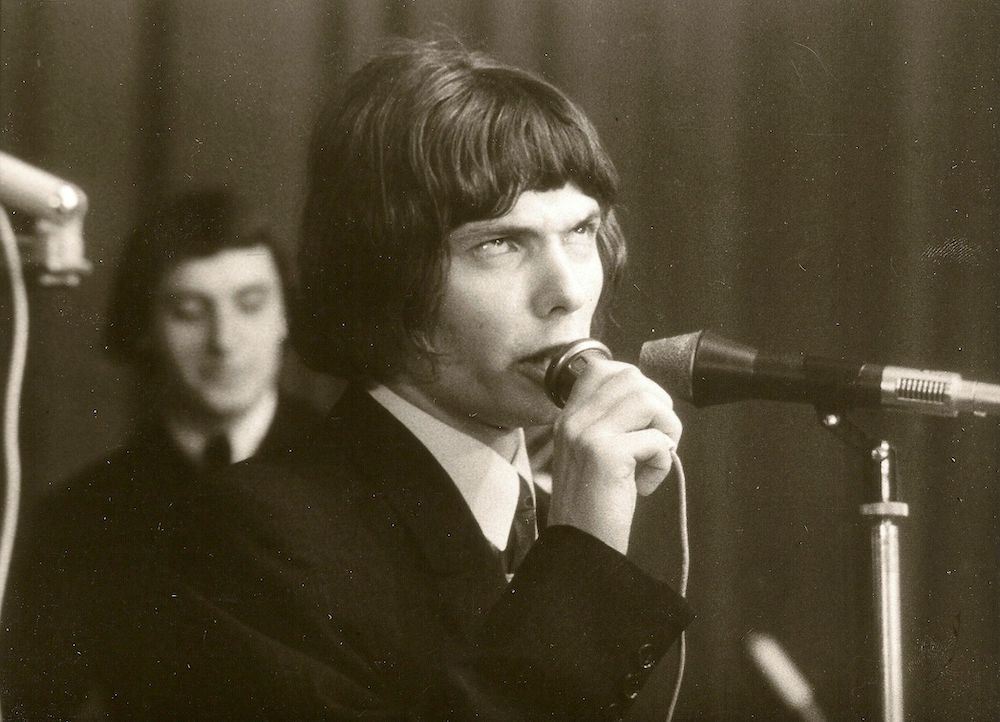

Other films in the series are somewhat more conspicuously light-hearted, including 1971 Polish slapstick construct I Hate Mondays, the 1967 Latvian rock ’n’ roll musical Four White Shirts, 1965 Lithuanian anti-war whimsy March, March! Tra-Ta-Ta!, and 1960 East German farce What Would Happen If…? You might wonder how 1964’s Czechoslovakian The Barnabas Kos Case managed to get made, with its tale of city orchestra power-mongering an obvious allegory for corruption at the top. Even more so 1970’s Case for a Rookie Hangman—which did earn blacklisting for Pavel Juracek (another Czech), who never got to direct another film.

On the other hand, Kira Muratova’s Ukrainian 1989 The Asthenic Syndrome (Sat/25, more info here) came late enough that it was allowed to provide a bridge to presumed new freedoms, dubbed both the “last Soviet film” and the “first post-Soviet” one. Her 153-minute epic blurs all lines between realism and fantasy, comedy and tragedy, experimentation and analysis, channeling the prior decades’ institutionalized repressive madness into a cri de coeur at once outrageous and resigned. It is a match held to the bonfire of the outgoing Soviet Union, revealing nothing but disunity. In a better world, Ukrainians and Russians alike could now regard its eccentric vision as a gravestone for an era happily long-gone…but, er, well. The more things change, the more they stay the same, right?