In the introduction to her essential new anthology of “garden poems,” Leaning Toward Light: Poems for Gardens and the Hands that Tend Them (Story Publishing), Tess Taylor—a poet-gardener herself—quotes Gwendolyn Brooks’ 1970 poem about the preternatural effect of the great Paul Robeson’s thundering voice and the creeping human bond that entwines us, reminding that:

we are each other’s

harvest:

we are each other’s

business:

we are each other’s

magnitude and bond.

“In gardens and poems we find figures for grief and surprise, for loss and regeneration. Gardens and poems help us dwell and abide,” Taylor writes of the fertile mesh of earth and experience. Over the course of 200 pages, Taylor traces the furrows plowed by wordsmiths ancient and contemporary, global and next-door (often now both), bringing forth an efflorescence of ideas, emotions, and instructions on how to live (and die).

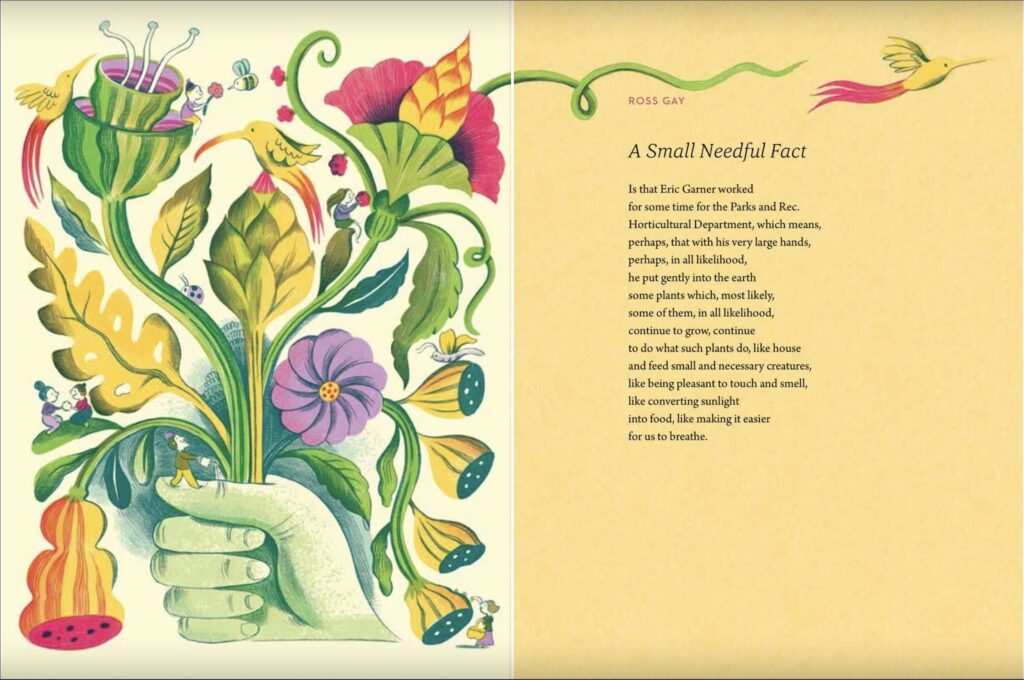

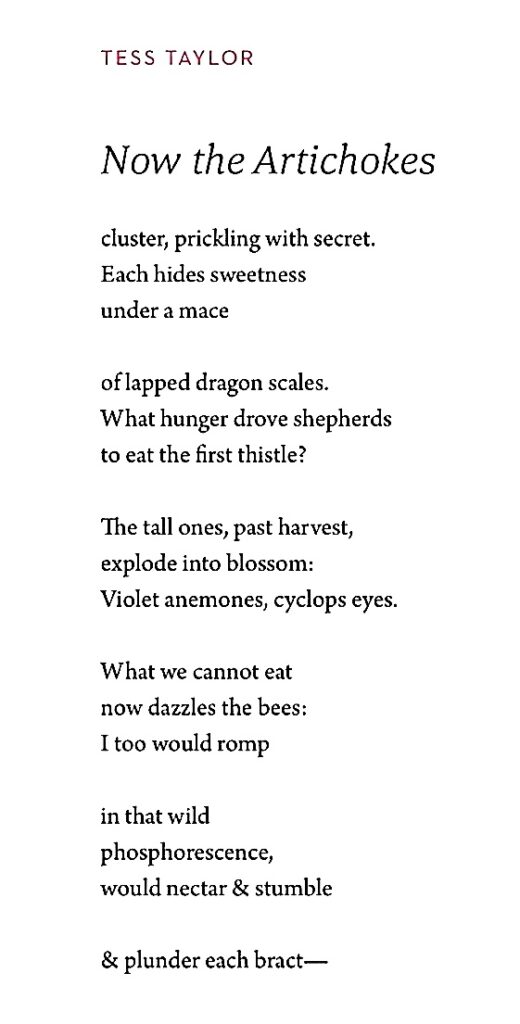

Young local poets like Alan Chazaro find space in the field next to historical giants like Virgil (the book ends with his ode to “fat, pleasing to Peace” olives) in sections like “Planting & Sprouting,” “Weeding & Wilding,” “Grief & Release,” “Wintering & Turning Again,” which echo farmers’ almanacs and epic poem cycles. Colorful pastoral illustrations by Melissa Castrillon, rustic recipes from some the contributors, and a layout that faintly recalls old Sunset gardening manuals add to the delightful effect, even as Leaning Toward Light takes on deep subjects like refugee trauma, climate crisis, and the effects of industrial agriculture.

Taylor is hosting a reading and concert to celebrate the anthology’s release at the UC Botanical Gardens at Berkeley’s Redwood Grove, Thu/24 at 5:30pm, and we’ll hopefully see more of her and her tremendous contributors around town as the launch continues to roll out. I asked Taylor about how she put the book together and how it reaches beyond the obvious metaphors to gather together the human experience through tenderness and careful attention.

48 HILLS I love that in her foreword, writer Aimee Nezhukumatathil points out that the word “anthology” is etymologically rooted in the phrase “gathering of flowers.” How did this book come about? I know you mention you were asked to do it—and as longtime poetry reviewer at NPR’s “All Things Considered,” the author of five books of poetry, and a gardener yourself you are certainly qualified.

TESS TAYLOR I love that fact about “anthology,” too—and it was certainly fun gathering this bouquet of poems, which is so beautifully illustrated by Melissa Castrillon. The anthology came about this way: A friend of mine, who knew me in the days I was working on a farm in the Berkshires in Massachusetts, called me about a year into the pandemic. She felt that there was a hunger for an anthology like this in the world, something diverse, earthy, contemporary, about what it feels like to tend plants now, why we do it. She thought I might love the project.

The day she called I’d been out in my yard putting in these cool fog-resistant tomatoes that our neighbor starts in his backyard and then shares with the whole neighborhood. I garden in our front yard and it’s a way of talking to people and coaxing the possibility and abundance out of what would normally be a lawn. It was still deep pandemic time, such that talking to a neighbor at a distance and sharing tomato starts felt like the kind of thing that could get you through a day.

My parents taught me gardening at a community plot near the graduate student housing in Madison Wisconsin. I’ve gardened everywhere I’ve lived—Berkeley, Brooklyn, and again on that farm—and I did youth programming for a community center that helped do both gardening and food outreach to at risk youth. I have worked in farmer’s markets, and even for a little while at Chez Panisse.

I am pretty passionate about the places where when we take care of the soil and the food we can build more abundant community. So when I had this chance for my poet self and my radical food gardener self to hang out, well, I leapt at the chance!

48 HILLS Can you explain a little by what is meant by “garden poem” and what are some examples you may have grown up with or that still inspire you? For me Marianne Moore’s famous observation that poems are “imaginary gardens with real toads in them” sprang to mind.

TESS TAYLOR You know, people have a deep relationship with plants and with cultivation, and with cooking and with eating, and also we love gardens, so there was a lot to think about.

The word “paradise” means walled garden in Persian, and you could think of the story of Adam and Eve as a poem. And then there are the “green shades” that show up in Andrew Marvell, and theoretical gardens in Moore. Add to this that poems and gardens share a kind of congruence: They are dense, cultivated spaces that let us see something—a plant, a word—with greater attention. So there’s also the idea that there are those kinds of overlap as well.

In the end, I probably could have made huge volumes of poetry, a whole history of poems that touch on or weave through gardens. What I chose, though, was to pick mainly contemporary poems that really had something of the hand to the soil in them, planting or picking or cooking or, sometimes watching and waiting. Some older friends—Virgil, Lucille Clifton, John Keats, snuck in—to remind us of the long conversation we’re in. I also wanted diverse voices. There’s been a lot of “ye olde” garden books out there; the fact is this is a beautiful and diverse tradition, and becoming ever more so as poets writing in English hail from more places on the globe. I wanted this garden to call to the body, to find the body gardening, and to welcome and represent everyone who came to feast.

48 HILLS As you refer to above, Leaning Toward Light has such a terrific breadth of contributors—well-known poets like Walt Whitman, Thom Gunn, Cole Swenson, and Czeslaw Milosz, as well as up-and-comers like our own former contributor Alan Chazaro and many poets of color. How did you come upon them, and what were you looking for as you pruned down possible inclusions? Are there any stories of particular poems or poets you really felt it necessary to include?

TESS TAYLOR One of the beautiful things about gardens is they immediately make our lives more diverse. You’re stopping the monoculture of a yard and inviting in microbes and compost on the soil level, and pollinators in the air, and hopefully many colorful plants inbetween.

When we are loving our gardens, we just want more color and life in them. I just got this incredible bi-color amaranth that is pink and green—it’s gorgeous, and on top of that you can eventually steam and eat it like spinach. I cannot say how much I love this plant, how the fact that it is colorful and nourishing and good for the soil and attractive to other pollinators and harvesting good minerals I’ll eventually be processing in my own body brings me joy.

Guess what? When we love the arts, they also make our lives more diverse. The arts are a place where we want this dense diverse beauty as well and where sometimes we are able to celebrate our stories in their glorious fullness. So, this anthology is a bit like that. We have some of the nourishing old voices that help prepare the great substrate of our language. And we have the voices that are talking urgently and beautifully about tending the plants that are near them now.

48 HILLS I was taken by your inclusion of a section for grieving and release, something which, to me, digs deeper into our relationships with gardens than the more common metaphors. And I can’t wait to try the recipe for Rainbow Roasted Root Vegetables that Danusha Laméris includes in the section introduction! Why were you particularly drawn to include this part? And what inspired the inclusion of recipes as well?

TESS TAYLOR I love the incredible poem by Danusha that accompanies the recipe, about grieving her child. When I read it, I stopped in my tracks, and realized that of course, one of the things that we do in gardens is we go to grieve. This idea that we go to watch the substance of life be transformed, literally, that we understand that beyond any one death is the material of new life—well, there’s a real reckoning there, with our own mortality, and fragility and also with the fact that we’ll also become soil and ash and air one day. Stephanie Burt once said we turned to poems to make the idea that we’ll die more bearable. I think we do that with gardens, too. That in the beautiful and unexpected transformations in gardens we also are able to perceive and have a kind of reverence for our own lives.

As for the recipes: I’m such a cook, and everyone was writing all these food poems, and it seemed like a good way to anchor us in time and season, to help ground some of the poetry in some of our other daily practice—cooking, eating— the place we touch the earth and its seasons, every day.

48 HILLS The nature art in the book by Melissa Castrillón is lovely, and it’s so cool you are doing a reading here at the UC Berkeley Botanical Garden. How did that come about, and will you be doing more events at other botanical gardens?

TESS TAYLOR Yes! Her illustraions are amazing. I had no idea about that, the press just found her and we worked on it and it was…. incredible. She’s just such a dreamy whimsical artist. As a parent I can tell you that one of the joys of small ones is being near beautifully illustrated books again. But why not more gorgeous illustrations for adults, for poems, for all of it? We deserve that place to breathe and bathe in color, too!

Collaborating with Melissa was just one cross-pollination. The other one that excites me is finding my garden friends across the country, and across the world. I think that all of our art forms are stronger when we cross-pollinate, so I am so excited to read at the Garden of Roses in Cleveland, and the Princeton Farminary, with the amazing thinker Camille Dungy. The Farminary is a place where seminarians do farm work and think about how that labor brings them closer to their calling. This kind of event makes my heart sing. Again, it’s an example of art and poetry being a vehicle that weaves us into stronger diversity, into community, into deep conversation about care and repair.

By the way, I just want to say that one of the reasons I added a section about grief is that we live in a time when we all carry a lot. The losses of this pandemic. The great sad days of climate grief. I have held a lot of tha—sometimes enormous numbness or sadness. Gardening alone doesn’t make it better, but there’s not a time when I garden that I don’t come out with a bit more willingness to try and to love, and something that I saw for which I’m grateful.

And poetry helps me access that kind of willingness to feel, to risk, and to love, as well. The great thinker Allison Gopnik says that we don’t care about what we love, we love what we take care of. When we plant a seed, when we dare to write down our world in a poem, we are actually building up that love. And for me, that’s been the exciting part of this journey—building a book that, even in this difficult moment, dares to hope.