For Anthony Discenza’s exhibition “Daemonomania” (runs through April 13), the entry to Et al.’s gallery space has been cordoned off with a dark green door made from floor-to-ceiling PVC strip, occluding its interior spaces from view. Typically used in the context of welding, these curtains protect the sight of those working in the vicinity of welders from the sparks’ harmful UV light, and related flash burns. This divider, muffling light and sounds between the spaces, marks a threshold. Other famous dividers like the green velvet curtain shrouding the Wizard of Oz and the iron curtain come to mind. Whether or not this Emerald Curtain is a direct reference, Discenza is suggesting not just a physical but an ideological or metaphorical protective barrier, one that urges us to suspend disbelief as we walk through Et al.’s front-of-house bookstore and into the artist’s speculative world.

On the other side of the portal, the first room of the exhibition is staged as a waiting room of sorts, complete with several rows of sleek airport seating. The inhospitable-by-design backless benches remind us not to get too comfortable here. But what are we waiting for? Aural clues point to a banal dystopia or purgatory, a not-too-distant riff on our current reality. A commercial beverage dispenser installed on the ground filled with dark brown sludge (asphaltic petroleum) whirs as it is slowly blended, and we hear siren-like calls from harmonizing feminine voices emanating from the next room. The waiting benches themselves are positioned towards an acrylic wall-mounted magazine holder filled with many copies of a publication created by the artist, which viewers are allowed to look through, but not take.

This publication is our first view into Discenzia’s approach to “synthetic images”. It’s filled with full-bleed photographs of artfully composed tablescapes in darkened rooms, laden with platters of meat, fruit, flowers, and tapered candles emitting wafts of smoke. Visually referencing the long tradition of vanitas still lifes, there is significance to be unpacked about the symbolism of each individual element. But the important takeaway is a reminder that we will die (and should all probably repent for our amorality while we’re at it.) This isn’t a dentist’s waiting room—we can’t escape this train of thought by switching to a copy of People magazine—the entire rack is filled with the same grimly beautiful publication. The subtle changes across the different still lifes represent a more interesting approach to AI-generated images than I’ve seen so far on the internet, one that emphasizes process and brings the changes wrought by hair-splitting prompt details into the physical realm. Flipping through the magazine brings to mind the idea of “trying on” different memento mori, just like one would visualize oneself in different outfits while flipping through a fashion magazine at the airport. (And what are we memorializing here anyways? Our own mortality, the destruction of the environment, or of the significance of images as we thought we understood them?)

A small ambrotype leaning on a shelf in the first room entitled Summonings depicts a woodsy scene with a cloud of smoke (or is it an apparition?) hovering between a clearing in the trees.

The ambrotype process is distinct in that the photographs function simultaneously as positives and negatives. Essentially underexposed collodion negatives on glass, they only appear to us as “positives” when mounted against a dark background. This callback to older photographic processes starts an interesting conversation when juxtaposed with the AI generated images in the nearby catalogs, but there is more in common between the two than first meets the eye. “Synthetic images” have been around ostensibly since the advent of photography as a medium, like Victorian-era spirit photography, which attempted to freeze the space between the living world and the next life into tangible form. The etymology of the term ambrotype itself comes from the Ancient Greek words for “immortal impression.”

Stepping through another Emerald Curtain, the quotidian dystopia continues. This room’s installation is immersive, with an entrancing melodic AI-generated vocal track (Somewhere, someone) transmitted through black cylindrical bluetooth speakers that are peppered on the ground throughout the space, and echo against the walls of Et al.’s cavernous galleries. An aluminum heat sink, typically used to dissipate the heat generated from electronic devices, is installed seductively on one of the empty walls like a ready-made Donald Judd minimal sculpture–a small protective gesture against the environmental hazards of technology.

On the floor near the back wall is a pile of 7,200 4″x6” glossy photos. The scattered images are vernacular in nature, not only because the form of the work replicates the quality and scale of a same-day photo service you might use to print images from a disposable camera at Walgreens, but also because of the contents of the pictures. The 72 repeating synthetic images in the suite of Burn Rate depict messy interiors in which coffee tables and kitchen counters are covered in crumpled papers, alcohol bottles, and detritus. The clutter is not quite hoarder-level, but it will be in a few years, if things keep going in this direction. There is a sinister, solitary quality to the scenes depicted, especially as a collection (one doesn’t get the feeling that this disarray is the momentary result of last night’s party with friends.) These overflowing eerie interiors echo with the earlier vanitas images, but with all of the abjection of confronting our own unsustainable consumption and waste, and none of the romance. Watching over the space, mounted high up on the walls of the gallery and adding to a sense of paranoia, are numerous motion-activated security lights entitled (Always) Touched by your presence dear. They flicker on-and-off, in a sequence that seems more unruly and uncanny within the context of the other sounds and images invoked into the room. I had to remind myself that there was no telepathic connection present when the gallerist jump-scared me by coincidentally walking out of the back office the moment I activated the lights.

Beyond the third and final curtain, Et al.’s smallest gallery space contains a bundle-wrapped palette of bagged anthracite from the Pennsylvania company Blaschak, whose logo is none other than jolly Santa Claus himself, waving as he pops out of a chimney, bundle of coal in tow. Aside from the implication that we have been naughty boys and girls (a mere ton of coal is a merciful punishment for the anthropocene’s transgressions), the raw materials related to petroleum products are some of the only elements in the exhibition that aren’t referred to by the artist as synthetic.

Anthracite is sometimes called blind coal, perhaps because it has a relatively “clean” burn compared to some other fossil fuels. Underground deposits of the material have been known to spontaneously combust underneath the surface of the earth, and can stay smoldering for decades. Thinking about these underground fires going unnoticed causes me to revisit the Summoners ambrotype, now seeing its smoke signal in a new light. The crude oil and the anthracite are both deemed “familiars” in their titles, a term which has multiple meanings but often refers to a spiritual guardian/daemonic entity that attends and obeys the commands of a witch. Discenza’s speculative environment is not far off from our late-capitalist reality that oil has such a disproportionate power on our society that its influence verges into supernatural territory.

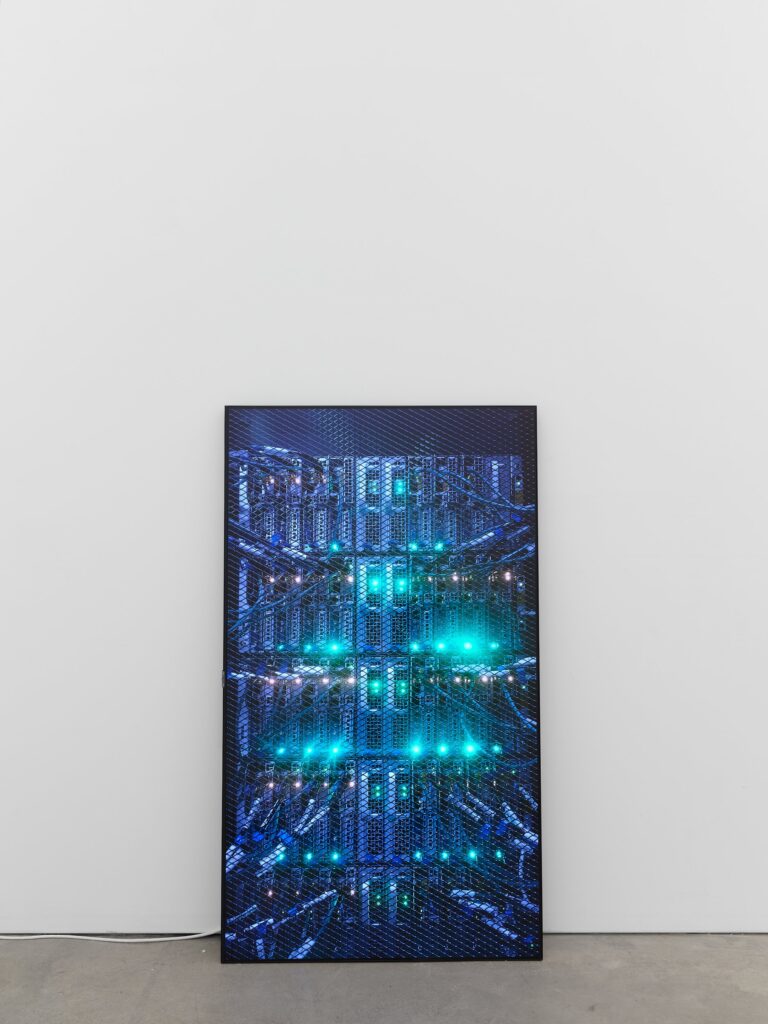

A nearby broom (Servant) adorned with a sticker of a smile sticking its tongue out winks to the sorcerer’s apprentice, a scene in Fantasia in which Mickey Mouse casts a spell in an attempt to make a broom to do his work carrying water for him. The animated brooms multiply and go too far, quickly escalating from loyal helpers to antagonists. We don’t even begin to understand the implications, joys, and pitfalls of outsourcing our labor to AI, Discenza reminds us. Not to mention, there is a very real material connection between fossil fuels and the data centers, one that is very easy to lose sight of as we press refresh on the seemingly endless possibilities of generative AI. We are left to reflect on a large vertically-oriented monitor displaying a 4K video of real-or-imagined server racks blinking intermittently, leaned against the wall like a mirror, entitled For Thou Wast a Spirit Too Delicate.

DAEMONOMANIA runs through April 13. Et al., SF. More info here.