People who’ve watched a couple seasons of Orange Is the New Black sometimes think they have a savvy understanding of what it’s really like in prison. It’s a panopticon that’s also like a de facto segregated middle school cafeteria, where long stretches of boredom are punctuated by acts of caprice and cruelty—and for every tireless do-gooder who believes the inmates are capable of re-entering society on their own two feet, there’s at least one sociopath.

The San Quentin Project: Nigel Poor and the Men of San Quentin State Prison, a collaborative exhibit at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (through November 17), complicates this picture somewhat through the use of found photography. Poor, who’s taught photography at the facility since 2011, has had to make up for the fact that her incarcerated students are not allowed to possess cameras, and the resulting collection comes from a cache of unarchived (and, in many cases, bizarre) photographs she was given access to by the prison authorities, presumably after earning the administration’s trust. Constrained by the inability to instruct people about apertures and f-stops, she taught them to perform close, often psychologically canny, readings of images.

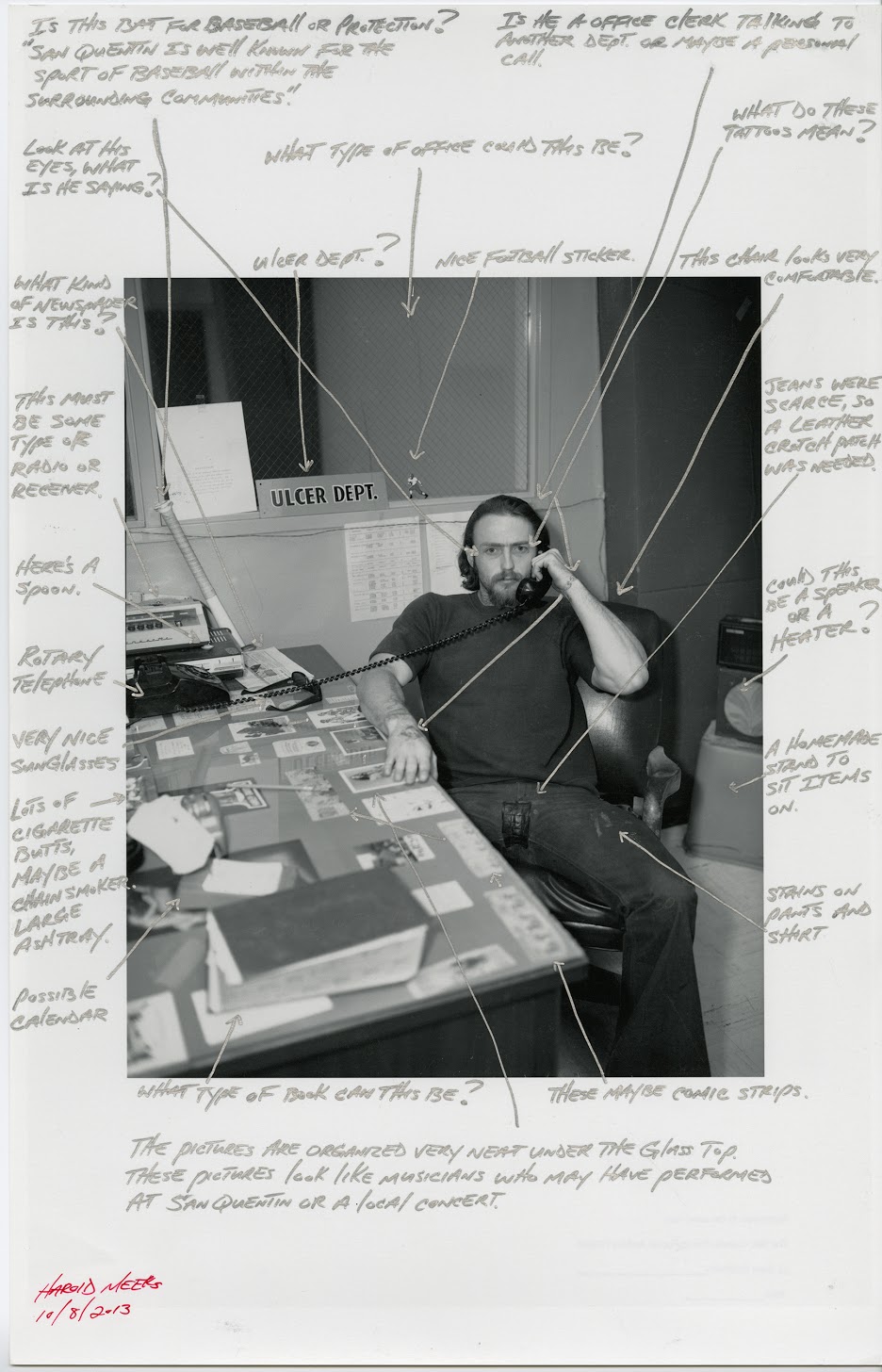

Unfortunately, the exhibit, which premiered at the Milwaukee Art Museum, isn’t always mounted in the most easily comprehensible way; viewers see the original photograph on one wall and then a heavily marked-up version, full of inmates’ marginalia, somewhere else. But the composite effect is strong, as a picture of life inside San Quentin accumulates from all perspectives.

Established in 1852, it’s the oldest prison in California, and the site of the state’s death row—inactive since 2006, and probably kaput, after Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a moratorium on capital punishment earlier this year. The “minimum-maximum” facility houses some 4,000 people. But most of the photos are from the mid-20th century, a time of fights, unlikely camaraderie, and sad Christmas trees decorated with paper (because anything sharp or breakable was almost certainly contraband). We learn that as recently as the 1950s, San Quentin had its own school, for the workers’ children. It’s impossible not to read the naughty expressions in a 1958 class picture and wonder if they would later return to San Quentin in a different capacity.

Of the shots taken within the prison walls, the photographs are often tender but seldom happy. If anything, happiness in prison is highly suspect, as in the image of a professional-looking man smiling into a cell. There’s no one else in the frame, so is he a neatnik warden taking pleasure in a tidy space, or something more sinister?

Weirder still is the image of an inmate, his new bride, and a clergyman all touching a marriage certificate. Facing to the side, the officiant is smiling, but the woman’s eyes are full of resignation over the life she’s about t embark on, an expression belied by her meretricious flower brooch. This one could be a Garry Winogrand, or even a Weegie—as could the one of a veterinarian (we assume) holding a stethoscope up to a cat that an inmate is holding.

Without few notations from San Quentin officials, Poor passes these photos onto us, to share in the wonder as to why these minimally catalogued images were even taken. But that’s what makes it interesting. And it’s clear some of the inmates had fun, too, combing through the prison’s past and offering a great deal of insight. Some of their speculations can be jarring, as when someone scrawls that a picture has been re-created or otherwise staged. A shot of a person, wedged in a crate of “tomato catsup” tins with only their hands and legs visible, looks a little too-perfect, less like an escape than someone demonstrating how to make an escape. It’s not all fun, of course: A cord tied almost in a mini-noose that dangles into the prison yard from a parapet suggests a lynching and a reign of terror.

There are bodies all throughout “The San Quentin Project,” often documented as if for medical purposes. Beyond the guys boxing or lifting weights, there are images of bruised, lacerated, swollen, wounded, and scarred men. A guard with an abrasion on his cheek looks ready to kill whoever did it. But the best photographs are the ones that leave you slightly confused, like one of a sad-eyed guy on the phone in some prison office. It looks to be the 1970s, and he’s manspreading so that we can see the crotch in his jeans has been patched. Behind him, there’s a baseball bat, and a sign on the windowsill reading “ULCER DEPT.,” a piece of self-aware office humor from the days before Dilbert clippings. Why was something so banal worth capturing? It wasn’t then, but 40 years later, it sure is, and Poor’s student Harold Meeks had a field day documenting every last detail, from the rotary telephone to the guy’s tattoos.

The most magnificent image—also from the ’70s, based on the hairstyles—is of a Black family, a smiling young man and his late-middle-aged parents. Everyone’s dressed up, so there’s no indication if the young man is an inmate or a staffer. But his mother’s body language and weary half-smile seem to suggest a prison visit. Her pained expression says she prays for her son, who she knows deep down to be good. It’s called “Mother’s Day.”

“The San Quentin Project: Nigel Poor and the Men of San Quentin State Prison”

Through November 17

Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, Berkeley

Tickets and more info here.