Going into a preview—as I did for Cutting Ball’s Rossum’s Universal Robots (through November 12 at EXIT on Taylor, SF)—one knows to expect a work-in-progress: maybe a line will be spoken late; perhaps a lighting cue will be off; someone’s costume may even split at the seams. This particular performance saw the denouement of the show literally stuck in the dark when actor Rebecca Pingree’s prop flashlight wouldn’t, y’know, light.

It’s to Pingree’s credit that she rolled with it without missing a beat, having her character declare “Thank God, this is a preview” and asking we audience to “just pretend there’s a light on my face.” The lines got applause from the entire house.

Incidentally, such a tech SNAFU was keeping in-theme with the show itself, in which humanity’s hubris in mastering the mechanical comes back to bite ‘em in the ass. Based on landmark 1920 Czech play R.U.R by Karel Čapek, the text is where the word “robot” originally comes from. Its last Bay Area production was the stylish 2018 show Universal Robots by Mac Rogers, put on by the now-defunct sci-fi-themed troupe Quantum Dragon. That show took several liberties and advertised itself as “inspired by” the 1920 original. This new adaptation by director and Cutting Ball Collective member Chris Steele also takes liberties and modernizes the classic Paul Selver translation, with some mixed results.

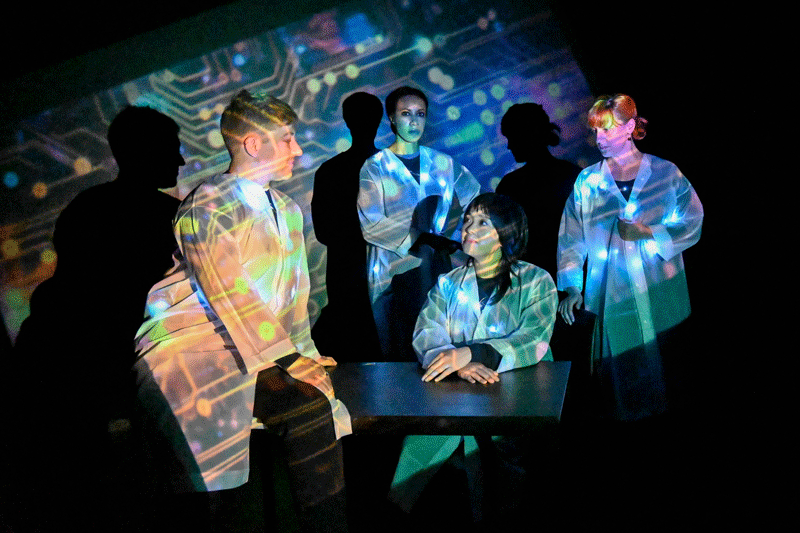

Before the show begins, we meet our four-robot ensemble (who walk out to music that I swear must have come from Captain EO) to tell us about the pageantry we’re about to witness. It’s about their creators, some species of bi-pedal meat sacks who once ruled the world before they were all killed. Each of our four—all with a device on the right side of their head resembling a cochlear implant with a blue LED—encourage us to discard outdated human concepts like gender, as they will be impersonating a number of characters outside the gender binary. (Some of the robots are played by pre-selected audience members who read their lines as projected on the screen.)

Eventually, we’re taken into the story proper, and the headquarters of the titular Rossum’s Universal Robots factory. Dr. Domin (Nic A. Sommerfeld) deals with a few customer complaints before finally welcoming the arrival of Helena Glory (Alexis Royeca), daughter of the President and a champion of robotic civil liberties.

Domin, though not quite Eldon Tyrell, is happy to boast of his company’s technological achievements, which have so lowered prices around the world (due to not having to pay automated workers) that he believes humanity is on its way to a post-scarcity society. But Glory sees the creation of a new caste system, one placed upon “workers” of humanity’s design rather than any traditional bias. She’s so bold as to argue that robots have souls which R.U.R execs are purposefully overlooking for the sake of avoiding any lingering questions of, well, humanity.

She may be more right than even she knows, but with her father now on shaky political ground, she may not be in a very strong position to make demands on the robots’ behalf. Not yet, anyway.

Although Steele and her collaborators create a visually interesting mix of the old and the new—the new script mentions the Internet and social media, while Carlos Antonio Aceve’s set has an old-school design reminiscent of ‘60s and ‘70s sci-fi—some of the problems of the classic text remain. For instance, although this play seems to allude to Stephen Hawking’s 2015 Reddit AMA (wherein he was asked about AI ethics and class warfare), using automatons as an avatar for the underprivileged creates the problem of the real underprivileged being seen as something other than human—this time literally.

Recognizing the “ghost in the machine” is a sci-fi staple, but there’s always a level of discomfort brought to the surface with stories that attempt to draw parallels to real-life bigotry, because it often oversimplifies that bigotry to “Can’t we all just get along?” pandering.

Another problem inherent to the text is that it’s too long. The epilogue is traditionally trimmed down or eliminated altogether, and it’s easy to see why: it begins to lean into the saccharine and conflicts with the strong—albeit apocalyptic—ending of the previous scene. In fact, Steele’s adaptation tries a bit too hard to inject humor in an attempt to lighten things up. Levity is fine, but there were definite moments of tonal whiplash in the show, as visually interesting though it may be.

Also a pleasant sight was the universal use of audience masks during the performance. I chose the final preview performance because it was the earliest of the too-few mask-required performances in the show’s run. Both audience members (including a grade school-age child, who wound up being one of the extra robots) and staff were good about keeping their faces covered, only occasionally shifting for drinks or snacks. It was a warm day outside and the comparatively-cool interior of EXIT on Taylor was a relief. Still, my Aranet4’s CO² levels were reading 2427ppm at the end of the two-hour-plus show (including intermission).

In a city currently infested with AI start-ups, South African oligarchs, and robot cars that regularly run over pedestrians (though they’re easily felled by traffic cones on their hoods), selecting R.U.R for adaptation seems prescient in hindsight. But many of the text’s problems remain as deeply imbedded as its most intriguing ideas. Even the best of intentions can only do so much with the sore-thumb parallels. Still, you have the chance be robot in front of your fellow audience members.

ROSSUM’S UNIVERSAL ROBOTS runs through November 12 at EXIT on Taylor, SF. Tickets and further info here.