By Tim Redmond

DECEMBER 4, 2014 – The California Public Employees Retirement System, the largest pension fund in the country, announced this fall that it will stop investing in hedge funds, which are lightly regulated, opaque, and have a mixed performance record.

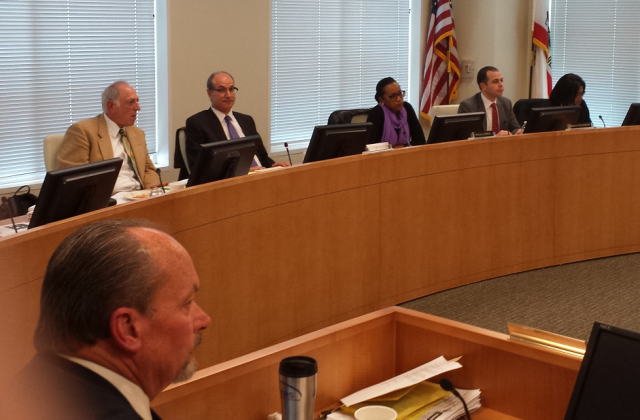

But the San Francisco Employee’s Retirement System is going the other way: It’s considering shifting as much as 15 percent of its $20 billion in assets into hedge funds – and yesterday, a room full of retirees argued against the plan.

And it sets up an interesting challenge: Will the board, made up of elected and appointed members, follow the advice of its consultants – or will it do what the people whose money is on the line want?

The concept has been in the works for months. It’s driven by the SFERS staff and board chair Victor Makras, who argue that the current investment strategy isn’t bringing in high enough returns.

The retirement fund has a target of 7.58 percent, and its current portfolio is coming in a bit below that. Hitting the target would allow the fund to reach the level where all current liabilities are covered. Right now it’s a little more than 90 percent funded.

We’re not talking disaster here: The returns are close to target, the funding level is close to target, and nobody’s missing a pension payment. But the city has to make up the difference when the returns fall below the necessary level, and in past years, that’s cost the taxpayers hundreds of millions of dollars.

It’s also led to calls for pension reform that have uniformly hurt the city’s unionized workforce.

The fund currently has 65 percent of its money in the stock market, 25 percent in bonds, and ten percent in real estate and cash, a report presented to the board shows.

But in this low-interest economy, returns on bonds and cash are very low. The stock market has been doing well – but nobody expects that to last. And a bust could have a major impact on the health of the fund.

“Two large declines have caused our funded status to decline from 178% in 1999 to 93% at June 30, 2014,” a memo from the board notes.

Hedge funds are different from traditional investments in the stock market. The fund managers take greater risks and thus offer (sometimes) greater rewards. They also use complex financial instruments to guard against losses when the overall market performs badly.

Since they’re only sold to institutions and wealthy individuals who can afford to take losses, they’re not as tightly regulated as traditional stock-market funds.

The SFERS consultant, Angeles Investment Advisors, recommended that the board put some money into hedge funds, and some board members agree.

Board member Joseph Driscoll, a captain in the Fire Department, noted that “hedge funds are designed to reduce risk. Hedge funds are less risky.”

But Board member Herb Meiberger, a certified financial analyst and retired city employee, had a very different perspective. He’s asked the board to ban any investments in hedge funds, and said that the information provided to the board at this point wasn’t objective.

“We need an objective analysis, not blinders,” he said, “not ‘I want a hedge fund and we need data to support it.’”

He also said that an investment advisor should look at what’s suitable for the client. “The customers are in the audience,” he said. “And they are clearly unhappy with this.”

Cynthia Landry, chair of the Retirement Security Committee at SEIU Local 1021, told the board that “there is a tremendous amount of uncomfortableness with this.” Not only of the dozens of speakers – mostly retired city employees – who spoke on the issue supported the idea of their pension dollars going into hedge funds.

One issue: The risks. Hedge funds have done very well in the past, but of late haven’t done as well at all. Part of the reason is the fee structure: The managers tend to take two percent of the assets and 20 percent of the profits as annual compensation.

CalPERS found that with the fees deducted, the returns weren’t as good as the more traditional portfolio.

There’s also the problem of transparency. The city can decide, for example, not to invest in defense contractors or tobacco companies – but hedge fund managers don’t tell their clients where the money’s invested. Hedge funds could be putting city workers’ retirement money into real-estate syndicates that are buying and flipping houses and causing evictions in the city – and nobody would know.

Makras and the board staff say that hedge funds provide a middle ground – higher returns than bonds, but less volatility than stocks. And there are other private and public pension funds that are moving in that direction.

But Rebecca King-Morrow, a Department of Public Health nurse, argued that “just because others are jumping off the cliff doesn’t mean we should.”

The retired city employees and their unions – at least, the ones who showed up yesterday – are pretty unanimous that they don’t want to go forward with this policy. Normally, an investment advisor whose clients nix a recommendation has an obligation to back off.

The members I met today are a pretty well-informed group. They know the importance of return on investments; they know the consequences if the fund doesn’t meet its goals.

And they don’t like this proposal

The board is not clear on how to handle the situation. “We have not had a solid conversation about our priorities and risks,” Sup. Malia Cohen, an ex-officio member, noted. “I’m not going to articulate my position today.”

It didn’t help that the latest proposal from Angeles arrived just a few days ago – not enough time for the staff or the critics to analyze the numbers.

So the board agreed to postpone a vote on hedge funds until January or February. But the overall issue – how to balance the desires of the constituents and the financial proposals of investment advisors – isn’t going away.