It’s been a very long COVID winter for the San Francisco Silent Film Festival (Thu/5-Wed/11 at Castro Theatre), which could hardly go the online “virtual cinema” route of many other such annual events: Absolutely key to their whole mission is the commitment to showing movies the old-fashioned way, projected onto a big screen in an honest-to-gawd movie palace, with live musical accompaniment even.

Ergo the 25th anniversary SFSFF, originally announced for 2020, then 2021, brings to the Castro Theatre a backed-up plethora of treasures including no less than 19 recent restorations over a full week’s course. Some of those restorations were done under the auspices of the festival itself, starting with an opening night world premiere of a restored Foolish Wives, accompanied by the SF Conservatory of Music Orchestra playing Timothy Brock’s newly commissioned score.

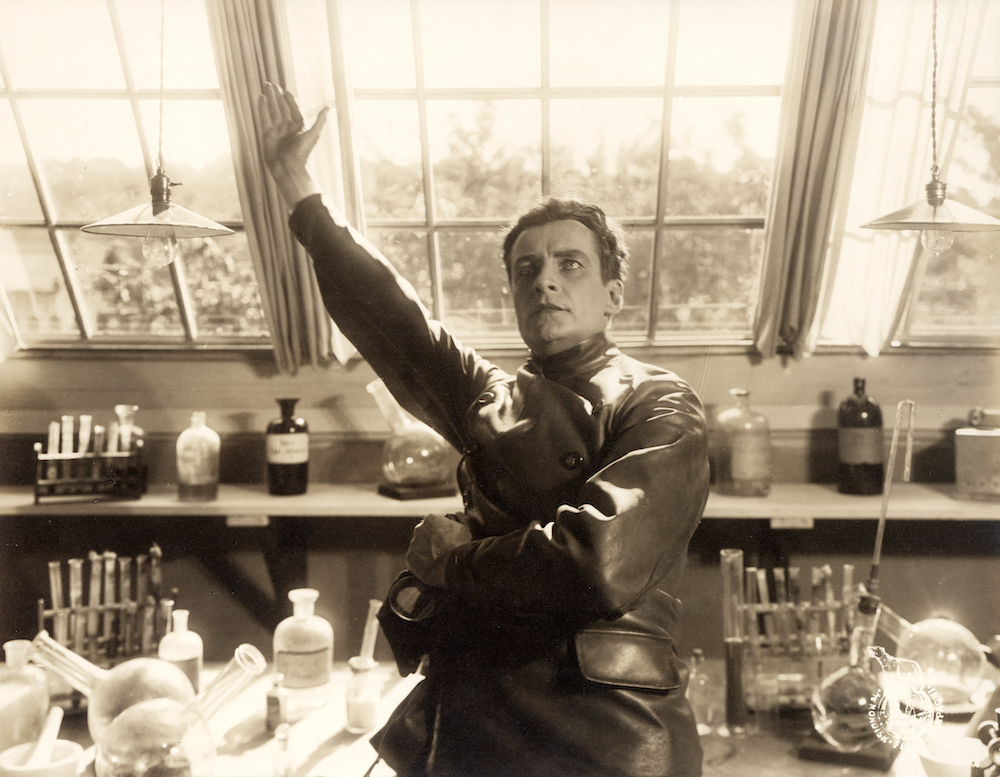

An endeavor by both the Silent Fest and New York’s MoMA, the refurbished Wives was the motion-picture scandal of 1922—and a Hollywood industry scandal before that, as director/writer/star Erich von Stroheim’s perfectionist shooting and editing processes drove production costs sky-high. For audiences, at least, that paid off in a lewd extravaganza pitting American innocence against European decadence, as the monocled, chrome-domed auteur played a sleek con man bent on seducing (and defrauding) a bored diplomat’s wife in Monte Carlo.

Von Stroheim had a vast mockup of the posh casino capitol built in Monterey, but it was the racy innuendos that got Wives denounced from pulpits nationwide. His legendary extravagance would put the kibosh on his directorial career by decade’s end, despite his films’ prestige and popularity—they were simply too expensive to turn a profit. The day after this kick-off, SFSFF is also showing the man’s debut behind the camera, 1919’s Blind Husbands. Telling a very similar story on a less grandiose scale, its runaway success amongst thrilled/shocked viewers turned “The Man You Love to Hate” into the talent studio executives were most tempted and tormented by throughout the Roaring Twenties.

The rest of anniversary Silent Fest program includes some other famous titles, including “Man of a Thousand Faces” Lon Chaney’s breakthrough costume epic The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923), episodic German Expressionist classic of the macabre Waxworks (1924), and the inevitable Buster Keaton showcase, his 1928 last truly great feature Steamboat Bill Jr.

More on the notorious side is 1922’s Oscar Wilde-derived Salome, a showcase for stage legend Alla Nazimova whose extreme Aubrey Beardsley-inspired designs (by Natacha Rambova, then Rudolph Valentino’s spouse) and purportedly “all-lavender” cast made it arguably the movie most permeated by a gay sensibility that Hollywood would allow for decades. There’s also D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, the film history milestone and racist-propaganda nadir, offered in a “live remix” by Paul D. Miller aka DJ Spooky dubbed Rebirth of a Nation. His 70-minute deconstruction should be considerably easier to take than the three-hour original.

Fabled filmmakers who lasted well into the sound era are represented by Japan’s Miklo Naruse (1933 very late silent Apart From You), France’s Julien Duvivier (1929’s The Divine Voyage), insanely prolific Hollywood lifer William Beaudine (who went from the respectable delights of 1923 Penrod and Sam to such later no-budget wonders as Jesse James Meets Frankenstein’s Daughter), and German expat Ernst Lubitsch. That last-named was the only person, no doubt, who could have miraculously kept Wilde’s wit intact in a dialogue-free 1925 version of Lady Windermere’s Fan, which closes the festival on Wed/11.

In addition to the nations whose film industries were already flourishing in the silent era, SFSFF’s current edition features works from locales as far-flung as Sweden (A Sister of Six), India (1925 spectacular Prem Sanyas aka Light of Asia) and Brazil (Limite, see below). As ever, each program will have live musical accompaniment, whether from a variety of soloists on the Mighty Wurlitzer or from ensembles including Club Foot Hindustani, Classical Revolution, and the Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra.

Here’s just a few of the lesser-known titles on tap that are well worth a trip to the Castro:

Arrest Warrant

Set in the days of civil war just after the Russian Revolution, this 1926 production from the Ukraine has the wife (Vira Vareckaja) of a Boshelvik combatant left alone with their son and some top-secret documents when he goes off to fight. Soon this border town is captured by enemy White Army forces, she’s arrested, and her refusal to betray the cause gets brutally tested. Hearhii Tasin’s drama starts out less radical in style than more famous Soviet films of the era. But as the heroine unravels under pressure, it begins piling on a full array of expressionist and proto-noir stylistic gambits to illustrate her disintegrating sanity.

A nonfiction complement to that fictive narrative can be found in Man With the Movie Camera director Dziga Vertov’s earlier The History of the Civil War, a 1921 compilation of on-the-fly combat footage that apparently hasn’t been seen in full-length feature form for a century. The fest is also showing 1930 quasi-documentary Salt for Svanetia, a poetical look at village life in the Caucasas Mountains that was an early effort for the visually innovative Mikahail Kalatozov, whose most famous films (The Cranes Are Flying, I Am Cuba) lay decades ahead.

Dans la nuit

Charles Vanel was already a movie star (and pushing 40) when he made this first, and unfortunately last, directorial feature. Set in his father’s hometown, shot there for budgetary reasons that greatly enhance the film’s almost neo-realist style, it has the hawk-nosed actor as a miner who whose raucous wedding to his sweetheart (Sandra Milovanoff) proceeds from cafe reception to carnival to carriage to conjugal bed. That inebriated, highly cinematic merriment consumes a full first half hour here, and it’s dazzling.

Perhaps inevitably something of a letdown is the ensuing hour of melodrama, in which our hero is severely disfigured in a workplace accident, leading to Lon Chaney-style pathos and conflict. Still, that section is strong on its own terms (despite a conspicuously tacked-on “happy ending” apparently forced by the producers), and it is a great pity Vanel did not continue to work behind as well as in front of the camera. Probably that was due to Dans la nuit’s fate: Despite critical enthusiasm, it was released (in 1930) at a point when silent films no longer had any commercial value in France. Incredibly, he kept acting for another six decades, until his death in 1989 at age 96.

The Fire Brigade

This 1920’s version of Backdraft trades in Irish ethnic stereotypes and classic poor boy-rich girl romantic conflict as well as something rare in the silent era: Color. Charles Ray plays the youngest in a family of firefighters whose head is turned by a debutante (May McAvoy, who the next year would be in “talkie” breakthrough The Jazz Singer). Unfortunately, her wealthy father is mixed up with the corrupt city commission that is allowing a construction company to skirt fire-code regulations—resulting in lethal tinderboxes that may include a newly-built orphanage.

You can guess what happens at the climax. That big action setpiece is accented by the flaming hues of hand-tinting, while an early sequence at a charity ball features early two-strip Technicolor. William Nigh’s 1926 MGM production is a fun popcorn entertainment whose thrills are only lent further charm by some rather crude back-projection effects.

King of the Circus

Frenchman Max Linder was a very big star worldwide in the medium’s early days, a small, limber, dapper man with a singular persona as a tuxedo’d swell trying to maintain his dignity while forced into riots of physical comedy. Here he’s “Count Max of Pompadou,” a cheerful dipsomaniac who tells a chastising relative “My dear uncle, I cannot marry. I am a vegetarian.” He changes that stance upon falling for a trapeze aerialist (Vilma Banky), undertaking the trials of ridiculous acrobatic training when her father decrees she can only wed “another circus artist.”

This 1924 Austrian production was Linder’s last feature, and it is so funny you’d hardly guess at the unfortunate circumstances around it. World War I service had severely compromised his health a decade earlier, and despite support from admirers like Chaplin, an attempt to re-establish his career in Hollywood was a failure. When subsequent European ventures also fell short, he and his wife carried out a suicide pact just 18 months after King’s premiere. It was a great loss, not least because all his later “flops” now look thoroughly delightful, this one included.

Limite

An extraordinary anomaly, this was the sole film made by Brussels-born Brazilian avant-gardist Mario Peixoto, who was just 22 at the time. Two women and a man are adrift in a boat at sea, seemingly in dire straits, despairing of rescue—or do they even want it? As they waste in the glaring sun, they think back to their lives on land, depicted in sequences no less cryptic and abstract.

With its languid pace and nonexistent “plot,” these two hours ought to be a pretentious slog. Yet there is nothing quite like it, certainly not in the silent era; it’s a photographically beautiful, mysterious, evocative film whose experimental poetry (and techniques such as solarized images) anticipate later innovators like Jean Vigo and Maya Deren. It languished in obscurity for decades, despite the admiration of figures from Eisenstein and Welles to Scorsese, before being restored in recent years.

Smouldering Fires

A great stage star who’d successfully transitioned to film a decade earlier, Pauline Frederick was beginning to “age out” of leading roles when this 1925 Universal drama appeared. It has her as Jane Vale, the very “mannish” chief of an inherited manufacturing company, a brusque and humorless taskmaster sensibly clad in men’s suits. When an enterprising low-level worker (Malcolm McGregor) has the chutzpah to stand up to her, she naturally falls hard. And while he harbors no romantic interest, his loyal defense of her to factory gossips somehow gets misinterpreted as a marriage proposal, which he’s too nice not to follow through on. Alas, Jane has a collegiate kid sister (Laura La Plante) whose insipid youth and beauty naturally stir True Love in the husband’s heart.

This elegant soap opera ought to be hokum, but director Clarence Brown (who would go on to numerous Garbo vehicles, as well as classics like National Velvet and The Yearling) doesn’t treat it as such. And despite the plot’s somewhat anti-feminist gist, complete with climactic “noble sacrifice,” Frederick makes Jane a figure of wisdom and dignity rather than some “bossy old maid” type. It’s sort of a Joan Crawford role, and indeed the actress would have a last major success playing that lady’s “sophisticate” mother in talkie This Modern Age six years later.

A Trip to Mars

Though arguably no silent film is more famous or widely seen today than Metropolis, sci-fi was seldom seen onscreen in the era. One major exception is this 1918 Danish feature by local industry titan Holger-Madsen, in which the conveniently named “Captain Planetaros” (Gunnar Tolnaes) accepts a dare and builds a zeppelin to reach the Red Planet. Upon reaching it, his drunk, panicked crew immediately make a mess of things, prompting Martians to decree “War and sin! Killing and blood! This must be atoned for!” They, you see, have long since evolved beyond such primitive behaviors, and live in a sort of neo-classical utopia that looks like an Isadora Duncan training institute (with a little Midsomer tossed in).

This pacifist prelude to the likes of Queen of Outer Space and Nude on the Moon is equally daft in its way, with a scientifically laughable notion of space travel. But it’s also great fun, as well as cinematically advanced for its time, and impressively large in production scale. The mind reels at the fact that this elaborate endeavor was just one of eight films Holger-Madsen released that year alone.

THE 25TH SF SILENT FILM FESTIVAL RUNS Thu/5-Wed/11 at the Castro Theatre. For full program, schedule and ticket info, go to www.silentfilm.org.