Imagine there’s an answer presented at the family-friendly brainiac game show “Jeopardy!”: “All of them.” The snappiest bell-ringing contestant might say, for the purposes of this imagined competition; “What events at Litquake 2023 are most intriguing and offer spectacular fun?”

Certainly, the 50 events in the Bay Area’s largest annual literary festival (which runs October 5-21) and at least 44 events planned for its closing night in the Mission, Lit Crawl—all of them—are collectively spectacular. But that doesn’t preclude one particular gem receiving a moment in the spotlight. The Verdi Club on October 13 plays host to “Porchlight: Tricks Up My Sleeve.”

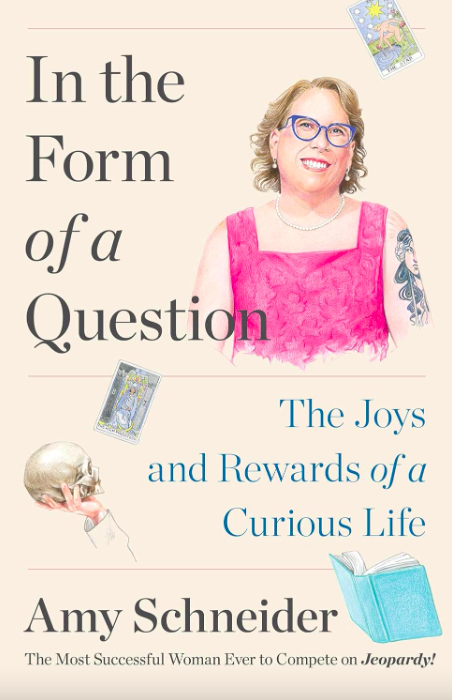

Among the writers telling their stories live with no notes will be “Jeopardy!” winner and author Amy Schneider. The 2022 champion is the most successful woman and trans person to participate on the show, and won 40 consecutive games. Her new memoir In the Form of a Question: The Joys and Rewards of a Curious Life (Simon & Schuster, $28) was released in early October.

In 21 short chapters that read like essays, Schneider plays a reverse “Jeopardy!” game, responding to questions such as, “When Did You Know You Were Trans?”; “How Did You Lose Your Virginity?”, “How Are You So Smart?”, “What Are You Going To Do With the Money?”, and others. (She won $1,382,000 during her two-month run.) Schneider’s writing style is candid, buoyant, and bluntly honest. If the book’s structure zigs and zags—and it does—it could be a reflection of the ADD she describes, and in part credits for her game show success.

Schneider’s always-curious-about-everything mind and the narrative arc bounce unreservedly between bold declarations on serious issues like being polyamory and the open marriage with her wife Kelly, to lighthearted statements of fact that speak volumes: “Trans people are just people. They need to pee sometimes.” An add-on section entitled “Let them,” drawn from her thoughts about gendered bathroom arguments, becomes both “potty humor” and pointed political education.

Asked in an email interview about the privileges and responsibilities of being a high-profile trans person, Schneider has much to say.

“It’s impossible to be a trans person without being a ‘trans activist.’ Trans people exist. They’re not lying when they describe their own experience and believing them doesn’t actually hurt anyone. Every time I walk out my front door wearing a dress, every time I introduce myself to someone as ‘Amy,’ every time I use a public restroom, I’m being an ‘activist.’ While I won’t deny that being on national television was a bit intimidating, because it gave exponentially more people the opportunity to attack me for my ‘activism,’ it wasn’t fundamentally any different from the life I already lived.

The only possible argument against trans people is that we’re lying, that (for example) trans women are actually men, pretending to be women in order to achieve some kind of nefarious desire. And that’s simply not true. So all any trans person has to do to fight that hatred, is simply be the exact person they actually are. It doesn’t take any effort for a trans person not to be scary. You just have to live your life exactly the way you want to. There’s nothing to be afraid of.”

Even so, she felt apprehension being a “Famous Celebrity Trans Person.” Initially, there was fear of being physically or verbally attacked, targeted for IRL or online hatred.

“But once that backlash didn’t develop, I started feeling a different pressure,” she admits. “In a way, I worried that I was too well-liked. What I mean by that is: what people knew of me was what they saw on ‘Jeopardy!’. And being on ‘Jeopardy!’ is one of the most normal, non-threatening ways a person can be famous in America.

While I was my authentic self on ‘Jeopardy, I wasn’t my whole self, in all of its complexity. Which isn’t a bad thing; “Jeopardy!” isn’t intended to show people in all of their complexity, it’s a nice family-friendly game show. But the fear became that my ‘Jeopardy!’ persona could be used as an unfair standard for other trans people to be held to. Like, ‘I can’t be transphobic, I like that nice Amy lady on ‘Jeopardy!'” Why can’t they all just be like her?’ I wanted to show that trans people can have complicated, messy lives, while still being ‘that nice Amy lady on ‘Jeopardy!”’ That became a major factor in writing this book.”

In addition to escaping the rancor she had anticipated, Schneider was struck by a topic that has not received as much attention.

“I did expect more people to have a reaction to my discussion of drug use in the book. Maybe it’s just a holdover from all the D.A.R.E. presentations I was forced to attend in childhood, but I thought that people would be more freaked out by the fact that I’ve partaken in, and enjoyed, psychedelics and cocaine. Apparently, we’ve moved farther on from War On Drugs hysteria than I (or most policymakers, apparently) had realized.”

Schneider loves to learn and expectedly, writing the memoir provided a load of lessons, from how hard it is to write a book to reshaping how she thinks about arrogance and heroism.

“I’ve enjoyed writing my whole life, but I’d never seriously expected my work to be seen by a wide audience. I knew more or less what I wanted the book to be like, and I was confident that I could do it, and that I knew what my voice would be. But once the deal was signed, and I knew that the words I was writing were destined to be printed on paper and sent all around the country, the pressure was paralyzing for a while.’

“The other major thing that didn’t turn out like I expected was that, when I first started out, I didn’t expect the biographical aspects of the book to be so dominant. As I said in my pitch meetings, ‘There will be some memoir-ish elements to it, but I’m not arrogant enough to think my life is all that interesting.’ But over the course of writing it, I realized that I’d just been expressing the reflexive self-deprecation I’d been raised with.

“First of all, everyone’s life is interesting, if you really look into it. We’re all the heroes of our own story, and since I don’t believe that there’s anyone from whom I feel I have nothing to learn, I can’t then say that other people wouldn’t have something to learn from me. And secondly, I really do believe that my life has been interesting. I feel like I’ve learned a lot of lessons that other people could benefit from, and my desire to talk about my life isn’t (or isn’t only) self-centered, but also stems from a desire to give others a shortcut to lessons I had to learn the hard way.”

In the Form is 272 pages long and Schneider originally aimed at an even higher page count, hoping to include more philosophical pieces. Eventually, reaching the “time’s-up” buzzer, she ran with chapters she believed were complete and successful. Her comments as the interview comes to an end confirms there’s another book waiting in the wings. “I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about the nature of language and communication, about the nature of money and its implications for capitalism and society, and a few other topics. If I’m fortunate enough to have the opportunity to write another book, my hope is to be able to go back to those topics. Learning is all well and good, but how can we ever have confidence that what we’ve learned is really ‘true’? I have thoughts.”

Our final hypothetical “Jeopardy!” game therefore needs no guesswork predictions. With “Amy Schneider has thoughts,” as the prompt, the question posed will be, “How can we ever have confidence that what we’ve learned is really true?” Hopefully, we won’t have to wait too long for Schneider’s answers.

PORCHLIGHT STORYTELLING LITQUAKE EDITION: TRICKS UP MY SLEEVE October 13. Verdi Club, SF. Tickets and more information here.