The atmosphere outside Zellerbach Hall on the UC Berkeley campus Sunday afternoon was tempestuous and unpredictable, with raindrops and temperatures falling and gusty, horizontal-slicing winds emptying the streets and sending pedestrians scurrying for cover. Inside the sold-out 2100-seat auditorium, the Bay Area premiere program of Pina Bausch’s searing 1975 The Rite of Spring, and a warm, elegant duet, common ground[s], choreographed and danced by Germaine Acogny and Malou Airaudo, brought all degrees of heat and eternal rituals to the theater.

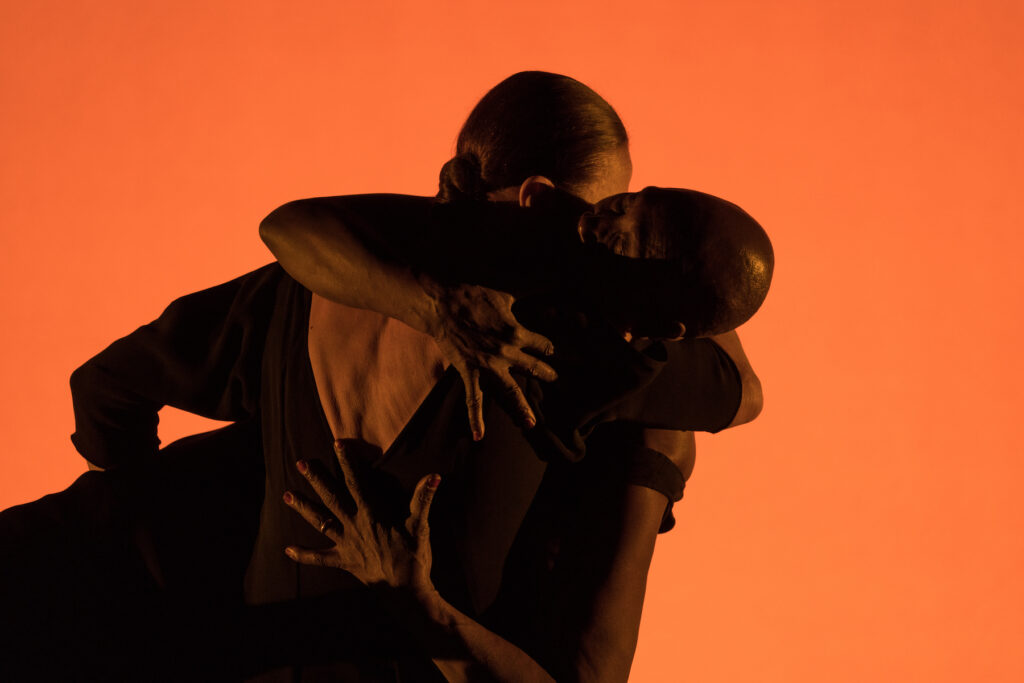

The performance in Berkeley that eventually rose to riotous ferocity—expectedly, as Igor Stravsinky’s score famously caused a ruckus at its 1913 premiere—began with the gentlest of tones. Complete darkness gradually dissipated as a coal-red glow spread across the backdrop and two dancers seated on simple wooden stools became evident. They faced upstage; their backs turned to the audience causing the form of Airuado’s torso to serve as first introduction and Acogny’s bare-back dress showing the power of the human body’s musculature.

The two septuagenarians are well known in their home countries: Acogny at age 79 is recognized as the “mother of African contemporary dance,” and Airaudo, 74, in Germany as a longtime dancer with Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch. If they are less familiar to American audiences, the stories told through their 30-minute, slowly unfolding duet’s physicality and a brief spoken interlude were infinitely universal and recognizable. These were two women opening up the wonder and weariness of motherhood, exchanging secrets and humor in friendship, displaying hard-won wisdom, responding to and finding respite from wicked world forces, and making softly visceral the profundity of whispering and peace found only by releasing oneself to relaxation.

With a delicious score by Fabrice Bouillon LaForest and few props—river rocks, three long bamboo-like poles used separately or connectively by the pair, two washbasins, a towel and the low stools—and costume designer Petra Leidner’s simple black dresses, the dance is so easy to consume that its more dramatic moments might be overlooked. One example; Airaudo “writes” with a river rock on Acogny’s exposed upper back. Or, instead of mapping the contours of scapula and spine, she is scrubbing the skin, erasing scars? It doesn’t matter which because the moment creates supreme intimacy beyond any of the couple’s actual embraces.

Intermission before the second act was a moment unto itself. Or more accurately, a 30-minute interlude providing a “task dance” as a copious carpet of peat soil was meticulously spread across the stage. Some people watched the crew in fascination; others used the moment chat with friends or escape into the lobby or outdoors under threatening clouds before returning to their seats. Anticipation was palpable as the house went dark. The work about to be performed by a breathtaking ensemble of 32 dancers from 14 African countries resulted from a collaboration between Germany’s Pina Bausch Foundation, Senegal’s École des Sables, and the UK’s Sadler’s Wells, and represented the first-ever Bay Are staging of the seminal work.

Ever since its premiere in 1913 at The Théàtre des Champs Élysées, Stravinsky’s tumultuous score that rearranged the universe of 20th century classical music by “repurposing” traditional orchestral instruments to encompass his beloved folk music’s unique instrumentation, vocals, and percussion, has stunned audiences. Created for Sergei Diaghilev’s Les Ballets Russes and choreographed by star dancer Vaslav Nijinsky with lighting and costumes by Nicholas Roerich, the original choreography depicting a pagan ritual—the sacrifice of a young maiden or “Chosen One,” who dances to her death—mirrored the dissonance and high-pitched intensity of the music.

In 2024, the upper range of the opening bassoon solo and angularity and dissonance of dancers’ movements are no longer jarring, but their mournful intonations and pitched wailing resonate nonetheless. The same can be said of every note, cymbal crash, arched back, crawl, leap, or fall to follow.

As the lights come up, a woman lies prone, her body splayed belly-down atop red cloth. Women arrive alone or in pairs, garbed in barely-there, off-white dresses. They sink into deep pliés a la seconde, knees open wide to either side, hands caressing along thighs or clasped into fists and driving into their crotches or the space below. Soon, the red cloth is picked up and signals a pulsating unison section with solo dancers bursting out to briefly find escape from incarceration in the group. Fisted or clasped hands, running, and off-balanced movements become signature, recognizable motifs.

Bare-chested men in flowing black pants arrive, casting the women into wary, tension-filled partial stillness. The mens’ movements emphasize weighted gestures, rippling torsos, and necks held like royalty expressing pride and dignity, not the stiff aloofness associated with European monarchs. As the red cloth that is the dress soon to mark the Chosen One is passed from one dancer to another, the women’s movements vacillate between tense stridency and lyrical passages; the men’s phrases become overwhelmingly militant.

Often, large ensemble circles form only to be broken by seemingly chaotic—but actually meticulously mapped—episodes during which dancers run pellmell, fling themselves to the ground, and women spring astride mens’ shoulders and fall precipitously, only to once again run. Most effectively, dirt is thrown into the air by the dancers’ feet and hair. The women begin to sweat and the dresses that have shown no markings from laying in the soil gain dark brown stains and smudges. Every face has dirt patterning unique to this performance, this real-life moment in the Rite of Spring.

When the dancer who will dance to her death is selected—on Sunday afternoon, the fascinating, multi-faceted Anique Ayiboe, a professional dancer from Togo—her performance at first holds palpable fear, despair, desperation, and remarkably, hope. Hope is a vital component of the mix, because it makes more tragic its disappearance as exhaustion like a thief steals it. The dancers watching encircle her, standing like pillars. Their blank facial expressions are eerily believable, bringing to mind the impartiality of crowds that in modern times fail to intervene when immense violations occur—and people who no longer even notice, let alone assist, the unhoused people populating big city streets.

After multiple non-curtain calls, heading out into the bluster of a Bay Area storm, the audience was left to reflect on rituals and traditions followed, broken, or lost. A person who missed the rare appearance can hope a second staging of the work by Bausch is not too far off. In the meantime, start with another, or a first hearing of Stravinsky’s marvelous music. The Cleveland Orchestra recording made by Sony Classical with Pierre Boulez conducting used in this production is a fine way to begin.