“My dad always tells me, ‘Stop making work about 6/4.’ He thinks it’s too political, that no one cares about the past anymore,” said artist Larry Li. But with all due respect, in recording his own family’s story amid Chinese history, Li is establishing an essential conduit. Combining found photos, drawing, and collage into his medium of painting, he tells a story that is both personal and inclusive.

Li was born in Mountain View and grew up all over the Bay Area, spending his formative years in Palo Alto. After graduating from Gunn High School in 2016, he completed a BFA at the University of Southern California’s Roski School of Fine Arts (2020). He went on to receive his MFA from Otis College of Art and Design in Los Angeles in 2022. Though currently a resident of Los Angeles, his family resides in San Jose and Li says he will always consider the Bay Area home.

“Over the years, I’ve been able to meet so many amazing artists in Los Angeles and really immerse myself in the community there. There’s no question that my work has been influenced by the vibrant visual language of Southern California. But I like to think I carry a little Bay Area swagger with me wherever I go, hopefully in my work as well,” Li told 48hills.

Li has kept a connection to Bay Area artists and particularly resonates with friends and fellow artists Maya Fuji and Esteban Samayoa. One of his biggest inspirations is Chinese contemporary artist and Bay Area legend Hung Liu (1948-2021) who left a sizable influence and legacy during her tenure at Mills College from 1990 to 2014.

“I have a deep admiration for the Bay Area arts community. Growing up here, especially in a city like Palo Alto, I feel there’s an urge to leave the bubble that you’ve been surrounded by. Los Angeles seemed like the place to go to pursue a career in the arts, and I think it was the perfect place for me to develop myself, but it’s an amazing feeling to know I can always look to home for inspiration,” Li said.

Li’s parents immigrated to the United States from China in the early 1990s and he credits them with being a primary influence on his subject matter as an artist. Like many immigrant families, Li says they arrived here with no knowledge of English, not much money, and worked extremely hard to raise him to the best of their ability. His parents’ journey deeply informs his art.

“Oftentimes my work takes me to places in history that my parents are often confused by, for example, my obsession with the Tiananmen Square Massacre on June 4, 1989. The student protests occurred during the time when my parents met in grad school in Beijing. They witnessed firsthand this traumatic generational event that created such an impact on western impressions of China. But to them, it’s something that they might not want to think about too often,” Li said.

Li says his family did not come from a background in the arts—his parents were both chemistry students. But even if his passions weren’t, strictly speaking, among their interests, they have always supported him in his creative pursuits.

“They know a lot of the work I do is about them, but we often don’t talk about it. There’s a mutual understanding that some things don’t need to be discussed, but are understood. I know they are proud of me and they know I look to them and our family for constant inspiration, but we will always keep that understanding at a comfortable distance, always awkward but never too tender,” Li said.

Beyond drawing from his own lineage, Li researches Chinese history, the Chinese American dichotomy, and cultural iconography, which he conflates and compresses into one picture plane.

“I think of my work as historical sampling. The same sort of sampling as referred to in hip hop music, the collaging of different parts of old songs into new beats. My paintings are essentially collage,” he said.

Li’s compositions are produced through digital collages that are then further realized through an integration of painting and photo transfers.

“There’s an almost problematic dependence and reliance on photography and sampling in my work. Everything draws from something that already exists in the world, there’s little in my work that is solely produced by my own imagination, but I doubt there’s anything in the world that is truly original now,” he said.

In sourcing images, Li says he “leans into and riffs off of” historical propaganda posters, kitschy Chinese auspicious symbology, journalistic photography, and family photographs.

“The work has always been an ongoing unraveling of cultural amnesia brought upon by the diasporic assimilation of our modern times. It is a pursuit to find visual language for third culture existence,” Li said.

Li points to the first piece he created in grad school, titled “My Government Has Gone Mad,” in which he juxtaposed a reinterpreted photograph of a mother mourning her son during the Tiananmen Square Massacre with a Chinese calendar backdrop dated May 25th, 2020, the date George Floyd was murdered.

Li’s studio is located in downtown Los Angeles in the creative hub of Mohilef Studios, a former industrial building that houses a community of approximately three dozen emerging artists. Having worked there for the past two years, Li says he is surrounded by artists, mostly painters, to whom he looks up.

“I have a lovely space with nice windows and natural light. I am a shy person, but my studio has no fourth wall and no door. It’s an open format where anyone moving through the rest of the floor will have to walk by my studio and say hi,” he said.

Li has come to appreciate this layout that urges a cross-pollination of sorts, because he says that if he was in an enclosed workspace, he would likely never be seen by anyone. Noting the solitary and sometimes lonely experience of being a painter, Li values the opportunity to be part of the Mohilef artists community. Earlier this year, Li sublet his studio while living in Shanghai for a two-month residency at the Swatch Art Peace Hotel.

“This was my first residency and I really got to experience the joy of not having any expectations other than to make work. It was an amazing opportunity to have a studio right across the hall from where I lived, waking up every day and being able to just spend the whole day at the studio. That’s something I’m not really able to do in my regular life,” Li said.

In the span of two months in Shanghai, Li created 17 pieces that he says are all very dear to him. He approached the residency without a specific plan or project in mind, allowing himself the freedom to create whatever he felt in the moment. This was in stark contrast to the work he amassed for his past four shows and later compiled into one large body of work, most of which has focused on the Tiananmen Square massacre and its role in his own family history. More recently, his work has shifted towards a viewpoint on Chinese propaganda art.

“I’ve always been drawn to old poster artworks that evoke social realism, while visualizing an idealized society with expectations of sincerity that always fall short through the almost forceful smiles in the working figures,” he said.

Li says he has always loved the colors, compositions, and deep skills implemented through this time period by sometimes nameless artists who were commissioned by the government to create work for the masses.

“I’ve been interested in sampling such works and taking this style that is so ingrained in culture and history, yet almost feels like a lost art, and reversing its role. Something once meant for government sanctioned art for mass consumption is now used to tell very personal stories about one individual’s family,” he said.

In this newer pursuit, Li has prompted himself to step away from his research and work about Tiananmen Square to take a deep dive into the art styles of 20th century China.

“Maybe part of me realized I can’t be making art in China about Tiananmen Square unless I want to have some very uncomfortable conversations, that were already not the easiest topic of discussion. I purposely chose to create new works that are more about highlighting culture rather than [being] bhistorically and politically charged,” Li said.

He admits that his interest in the story of Tiananmen Square will always be present in his practice but adds that it was never about the event itself, rather its proximity and role in his personal narrative. As his work continues to change and develop into new realms, one theme remains constant: family.

“My wife and I had our first child in June. To say this has affected my life and perspective would be stating the obvious,” he said.

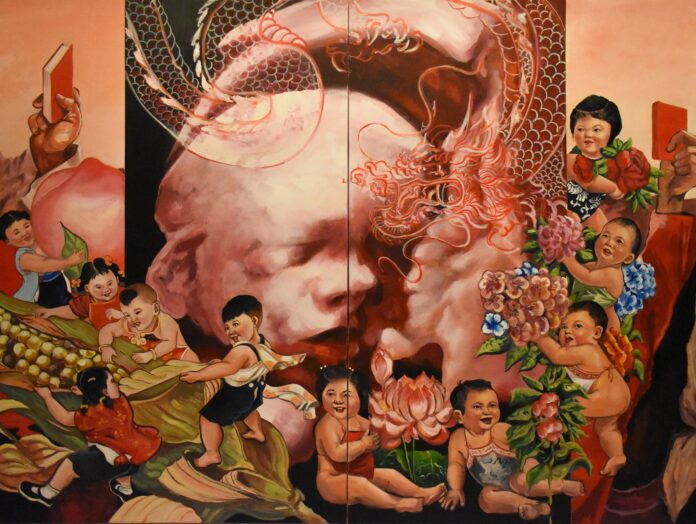

This awareness about the primacy of kin in his art first seeped in when Li arrived in Shanghai for his residency, and the first painting he created was titled “What’s a Dragon to a Dragon,” a portrait of his unborn son’s first 3D ultrasound with a superimposed image of a dragon—the animal representation of the Chinese New Year of 2024.

“Chinese baby cartoons that were collaged from different sources surround the large head of my baby. I see the babies holding flowers and harvesting corn as little angels guiding him into this new world. In the back you see two hands holding up Mao’s little red book, another sampled section of an old propaganda poster. I’m reminding him that he comes into the world with inherited histories that he has no choice but to carry, just like me,” Li said.

The rest of the work created during the residency emanated from that starting point, reiterating themes of time and family, significant moments between generations but inclusive of an aspect of looking forward. Li created numerous portraits featuring himself, his parents, and his sister as babies, as well as many pieces with the Chinese calendar.

“It seems I was hypersensitive to time and intergenerational moments,” Li said.

Li says that while initially excited but scared about the prospect of becoming a father at the young age of 25, he took his time sharing the news to allow time to process it more fully. He has since worked out that it will ultimately move his career forward.

“My work is so ingrained in my life and my family, and my family just got bigger. We welcomed our beautiful baby boy on June 5th at 4:48am. It has been quite a journey already. Lots of learning, adapting, sleepless nights, and unexplainable joy. His name is Kaden and he is a handful. He has a big attitude like his mama, but looks just like his pops.”

Li’s first solo show was “Ask Your Ma about ’89” at Residency Art Gallery in Los Angeles, which has represented Li since 2021. He will be included in a group show at Charlie James Gallery in September. He is currently working on his first mural commission for Destination Crenshaw, on a building owned and operated by AADAP, the Asian American Drug Abuse Program.

“AADAP was founded in the 1970s in South Central Los Angeles at a time when a lot of Asian American youth were especially at risk with drugs and violence. The organization has asked for a mural that highlights Black and Asian solidarity that promotes social justice in the Crenshaw neighborhood. My design titled Finding Siblings features a tiger and a black panther in front of a blooming orchid. The mural is set to be completed later this year,” he said.

Artist Larry Li says people have different reactions to his work. He has been told that his work is too specific and therefore limiting, the opposite of what he has always intended. But too, people of all backgrounds have reached out and told him that his work makes them reflect on their own culture and family—his favorite thing to hear about his work. Li believes that creating work about his own experience will continue to feed his soul, and also be an avenue towards reaching others.

“What I’ve come to realize making this work is that people are more similar than different,” Li said. “I believe as long as you focus on your own work and do what you want to do, other people will notice, and others will relate. Never pander to others—unless it’s the Chinese government during your two-month residency in Shanghai.”

For more information, visit his website at larryli.myportfolio.com and on Instagram.