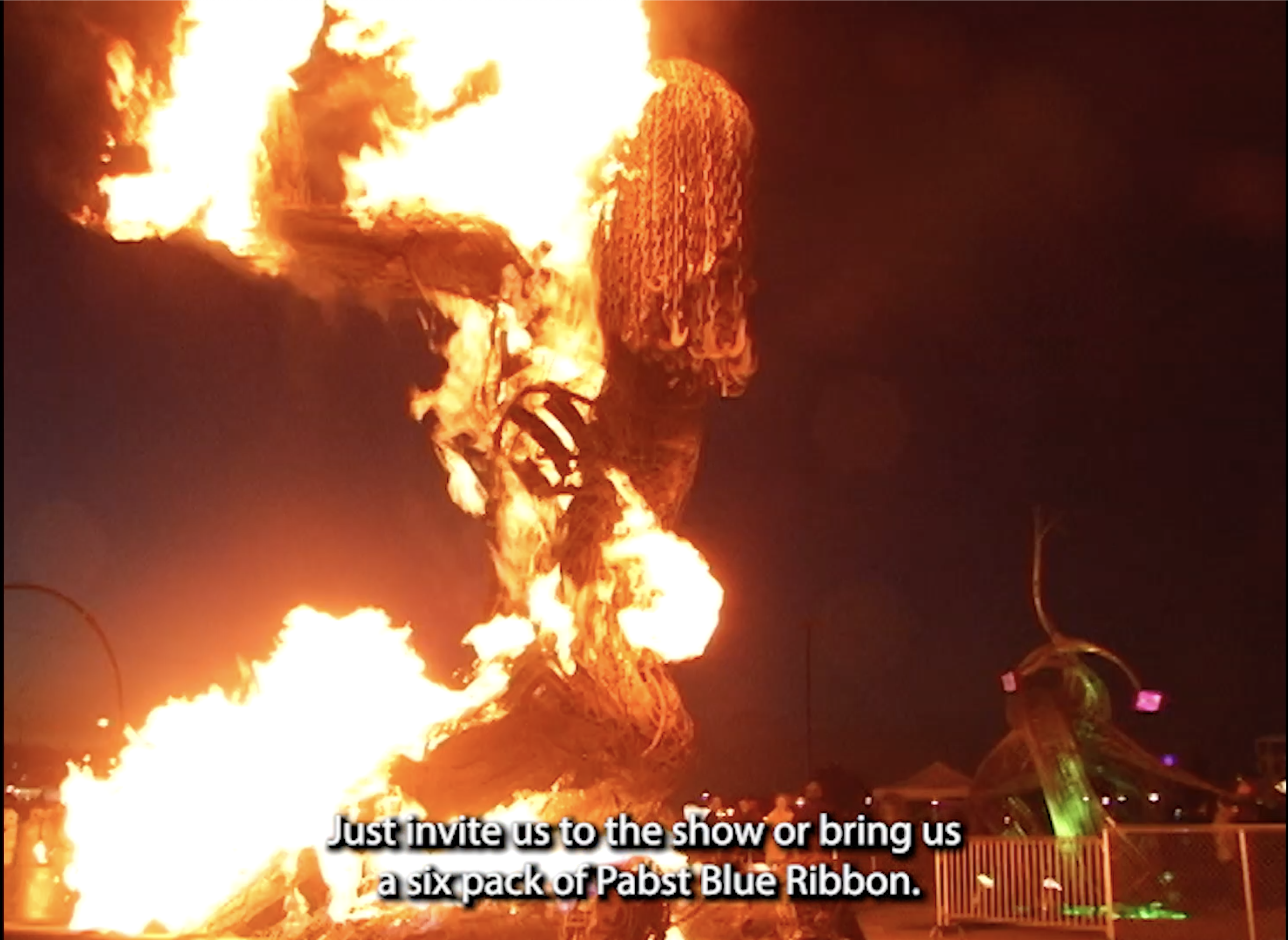

Artist Yasmin Mawaz-Khan was working with the Flaming Lotus Girls to make big art for Burning Man in the mid-aughts when she came to know and love Ace Junkyard (a.k.a. Ace Auto Dismantlers) in Bayview. It was a place where outsider artists could repurpose materials and find inspiration from the community of makers, visionaries, and weirdos in its orbit.

Today, such spaces in the Bay Area are rare, and only getting rarer, with serious threats to the survival of off-beat community hubs like Box Shop and American Steel looming large. Mawaz-Khan’s documentary Ace in the Hole—slated for release next year, assuming that its current crowdfunding campaign is successful—documents the Ace Junkyard’s quixotic effort at the end of 2009. The film narrates a battle for the Bay Area’s art community that rages to this day.

Ace wasn’t just a junkyard filled with dormant machines. It had a scene all of its own, a place where builder geeks would stage the annual Power Tool Drag Races in which they turned grinders, circular saws, and other tools into drag race cars. Impresarios held strangely compelling events like Cyclecide’s Bike Rodeo or Chicken John’s Lost Vegas, and fundraisers for big art projects. The vibe could be very San Francisco—owner Bill “the Junkman” Kennedy would regularly don drag for parties, appearing as alter ego Belinda.

But Ace Junkyard was also doomed. Like so many San Francisco industrial art spaces, gentrification, and eviction were coming for it.

“When I started to make this film, it was foreshadowing what was to come,” Mawaz-Khan said, citing a long list of iconic Bay Area burner and builder spaces that would also be closed down or converted to commercial uses in the years to come: NIMBY Warehouse, Cyclecide, The Shipyard, Survival Research Laboratories, the central waterfront space where Kal Spelletich built his robots, Michael Christian’s Xian Space, CELLspace, and big art studios on Treasure Island. Add to this list American Steel, whose new owners, Oregon investment firm SKG, are courting Big Tech in their sale of the property—and didn’t once mention “art” in the recent press release announcing the sale.

“It was the same story over and over again,” said Mawaz-Khan, who interviews all the builder/artist luminaries behind these spaces for her film. “And it’s been tragic to see it. There just aren’t any more spaces to explore and try things, like you can in a junkyard.”

I met Mawaz-Khan in 2005, when we were working with the Flaming Lotus Girls to build a big installation for Burning Man in the Box Shop on Hunter’s Point (which I wrote about in “Angels of the Apocalypse” in the San Francisco Bay Guardian and later my book The Tribes of Burning Man.)

The Box Shop, owned by artist Charlie Gadeken, is still the thriving home to the FLGs and other artist collectives. It seemed to be the exception to San Francisco’s downward trend of big industrial art spaces. The space has commissioned and displayed 110 murals by local street artists. Gadeken himself is fresh off his city-commissioned, critically acclaimed “Entwined Meadow” art installation in Golden Gate Park, and is preparing to install a new version of the work in GGP starting December 1.

“The Box Shop is the only remaining industrial art space in San Francisco,” Mawaz-Khan said. “It’s a special place.”

Unfortunately, the Box Shop’s days might be numbered as well. Gadeken feels the forces of gentrification closing in on him, and said the three-year lease he recently signed—with its staggering $6,000 per month rent increase—will almost certainly be his last.

“We’re pretty much going to lose our space in a few years,” Gadeken said. “The owner wants to put condos there. He wants to make more money.”

Gadeken, who has become a renowned installation artist, isn’t worried about his own art. He says he’ll probably rent a smaller art studio for himself in the East Bay, where many of San Francisco’s large scale artists have already fled (some of the latest examples being Gothic Raygun Rocketship and art car builder Sean Orlando, who just bought Richmond’s Seaport Studios’ where he will install 15 art and fabrication studios—most of which are already spoken for by future tenants.)

But Gadeken worries about all the smaller artists and art collectives that rent space at the Box Shop to bring their creative visions to life. The demand for more housing is squeezing out creative spaces in San Francisco.

“San Francisco is housing first, always,” he said. “That’s what they care about and that’s what it is. But we’re running out of places where people can make this kind of art in San Francisco.”

Mawaz-Khan finds it ironic—and a bit maddening—that there’s more demand than ever from big installation pieces in the commercial spaces that big corporations develop, yet fewer and fewer places to make that art here.

“It’s a question of what’s valuable,” she said. “Many corporations want big art now, but they won’t support the infrastructure where that art is being made.”

It isn’t just about the art. At issue is the survival of the communities that come together to make this weird, outsider art and in so doing, find an adoptive family—a theme that resonates among the characters profiled by Ace in the Hole. Kennedy came from a conservative upbringing and found support and acceptance for pursuing their gender identity and expression amid the wrecked cars, fiery parties, and nascent robots, art cars, and installation art. Mawaz-Khan has a Iranian-Pakistani background that also left her feeling like an outsider in the Bay Area before finding her groove and her people in Burning Man art world, and at Ace Junkyard.

“I finally felt like these are my people and I can be who I want to be,” Mawaz-Khan said. “That’s the heart of this film, these outsiders finding a place to belong.”

Ace in the Hole is almost halfway to meeting its final $30,000 fundraising goal to complete the film, a campaign that ends November 4. To contribute, visit this website. To learn more about the film (and watch its long trailer), go here.