They were still fine-tuning during the preview for the Museum of the African Diaspora’s fall exhibitions (which mostly run through March 3.) Almost none of the identifying cards were up, the screening room was closed with tech issues, and one exhibit was being installed on the third floor just as I was leaving. I was probably the only press guest arriving straight from home, with most others coming from a similar season preview at the de Young that morning.

As much as I would have loved to see what the de Young has coming up (especially since I haven’t been there in ages), I was probably more eager to see what the MoAD had in store. Highlighting marginalized voices is something the de Young can, with the right effort, do well, but it’s the MoAD’s raison d’être. To my pleasant surprise, the works I saw resonated with me deeply as I continue to watch my hometown take some very disturbing (and racist) turns—under a Black mayor, no less.

Most of the second floor is dedicated to “Spectrum: On Color & Contemporary Art” curated by Key Jo Lee, who has stepped into the MoAD’s newly-created role of chief of curatorial affairs and public programs. Lee told us that the exhibit means to ask, “How do we elevate, through color, everyday Black life?” Visitors are immediately greeted by Johanssen Projects alum Sheena Rose’s “Salt” (2022, acrylic on canvas). Rose’s style tends to stick to two-dimensional images and solid colors (though not all primary) in creating images of Black folks. In this case, we saw two Black women in white dresses in front of a long table, their hair obscuring the tops of their faces. Our hair remains a controversial topic, and Rose’s pieces embrace this by hiding her subjects’ identities. Their hair is their shared defining trait, yet they’re often shown in positions of power to which the hair seems a natural addition—certainly not a hindrance.

Basketball has a noticeable presence in “Spectrum”, starting with “I Want to Take You Higher” (1970, acrylic on canvas) from the estate of Barkley Hendricks. I had a tough time guessing the shape of the Pan-African-flag-colored piece, but the use of those colors seemed to compliment Felandus Thames’ “Motion in the Ocean #2” (2021-’23, Basketball rim, metal, soldering, and powder coating), featuring multiple basketball rims painted white and distorted out of their usual shape. It’s as if Black folks have become so ubiquitous with the sport, for better or for worse, that white representation almost seems like a distortion of the popular conception—an impression that was punctuated by the work’s close proximity to Hendricks’ piece.

Not many of the “Spectrum” artists were on hand that day, but their mostly-primary-color patterns lit up the MoAD’s second floor in their own unique way. (One particularly striking piece was Manyaku Mashilo’s new acrylic-and-ink “Grandmother’s Teachings,” an Islam-inspired piece that leans into the term “blood red.”) One artist who was on hand—with her family, no less—was Tawny Chapman, who typically works in photography.

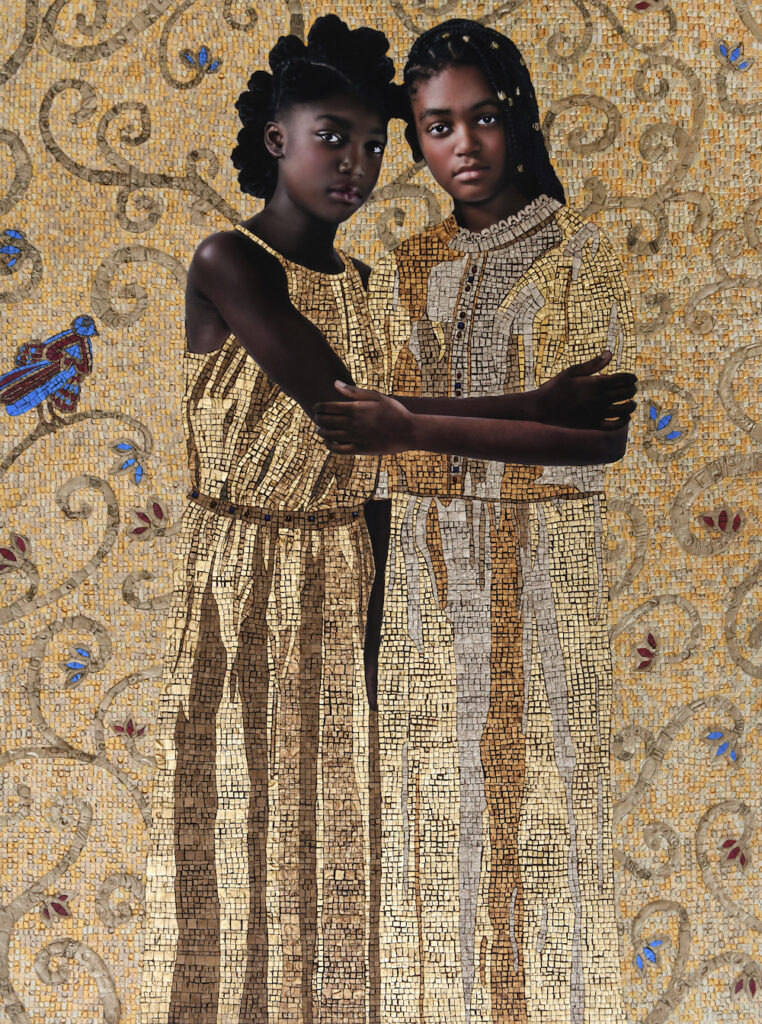

Chapman was noticeably adorned in gold during her visit, something that easily identified her as the artist behind the new piece “Iconography/A Hopeful Truth.” The photorealistic acrylic portrait of two Black girls features their dresses and background accentuated with (per the description) “24k gold leaf, 22K moon gold, semi-precious stones, and other mixed media on archival pigment print.” Chapman, who told us of her discomfort with public indifference to Black deaths, does nothing short of giving literal gold value to lives often regarded as worthless. Garish, perhaps, in its shiny excess (seriously, the piece literally “lights up the room”), but an intriguing inversion of that public perception.

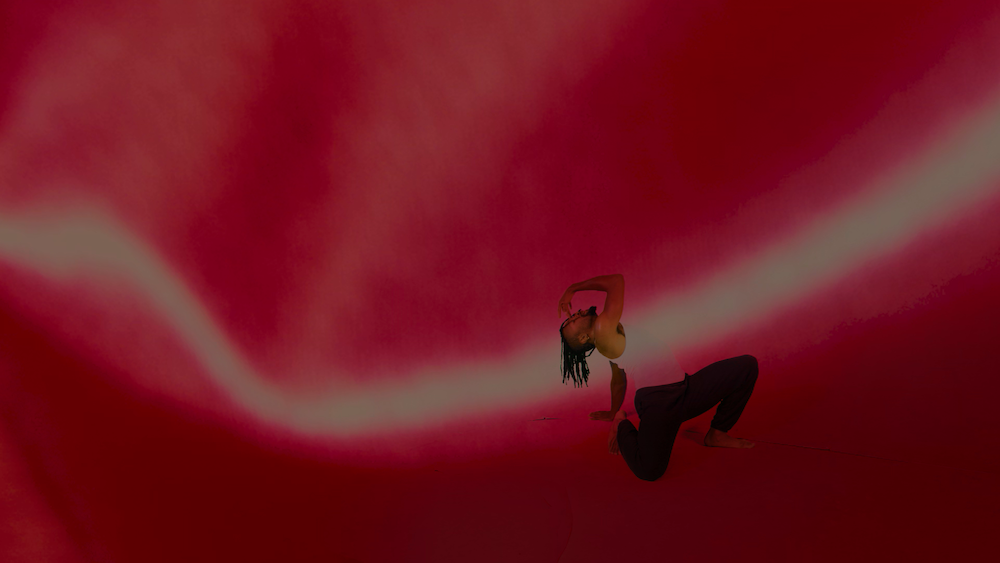

“Blood red” also figures into the emerging artist showcase for Salimatu Amabebe. Their solo collection “SON” (which, unlike the other current exhibits, only runs through December 10) finds the MoAD Salon fully decked out in burgundy, from the painted walls to the carpeting. It was inspired by the artist finding an old video of themself at age three dancing with their late father. A framed screenshot of it greets us upon entering the salon. It had them thinking of the power of learning through movement and repetition. What’s more, their recent gender-affirming top surgery led them to notice how much they resemble their father. To that end, most of the pieces in “SON” are tank tops coated in an adhesive to hold them in place, like the handprint of a ghost. Several of them are shaped into the form of a chair facing the wall, on which we see projected the image of Amabebe, adorned in a tank, dancing—perhaps as they once did with their father.

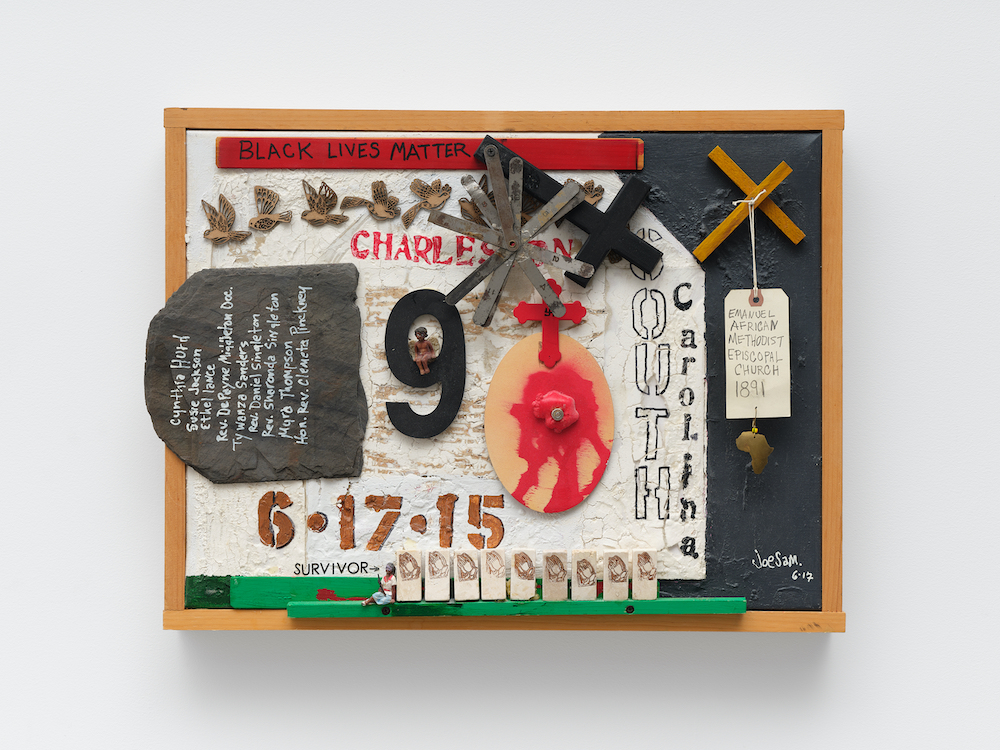

The top floor is dedicated to longtime artist and activist’s JoeSam’s found object showcase “Text Messages”, curated by Erin Gilbert. The name doesn’t allude to anything mobile phone-related, but rather, as Gilbert explains, “the message [the pieces] convey.” They feature everything from bullets and Confederate flags to piano keys and slave portraits, all collaged in a very Basquiat-esque commentary of popular Black imagery. (Speaking of Basquiat, his 1991 piece “One Quarter Self Portrait” features a version of Warhol’s “15 minutes” quote written in chalk.)

Standing in the middle of the third floor, with wood, electric, etc. images surrounding me on every wall, I couldn’t help but think of the recent homeless sweeps and proposed welfare drug tests that are more of a blight on San Francisco than actual tents. It may not be intentional, but considering the disproportionate number of Black residents caught up in those sweeps, it seems that our Black mayor is perfectly happy to criminalize both poverty and Blackness. It’s no surprise she never visits the MoAD for more than a photo op, nor that the striking images on display seem out of step with her policies. She’s probably already forgotten Banko Brown.

Sadly, I didn’t get to partake of the online exhibit, “The Only Door I Can Open: Women Exposing Prison Through Art and Poetry.” The exhibit (curated by Tomiekia Johnson and Chantell-Jeannette Black) was both created by and focuses on incarcerated women. I hope I’ll have time to do so soon.

In any case, the MoAD has a strong crop of material to showcase into the next year. Let’s hope that this new year finds the worlds outside and inside the museum resembling one another in a different way.

MOAD’S FALL 2023 EXHIBITIONS run through March 3—except for Salimatu Amabebe’s “SON,” which runs through December 10. Museum of the African Diaspora, SF. Tickets and more info here.