The Regional Housing Needs Assessment (RHNA), a product of the Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG), assigns to each Bay Area Jurisdiction quotas of new housing. Each city is urged to incentives and permit construction of its assigned number of new housing units, with some reserved for “very low,” some for “low,” and some for “moderate” income households. The majority of units to be built are supposed to be market rate units. Most of this new development is planned to take place in designated “priority development areas.”

These quotas, sometimes erroneously called a city’s “fair share” of new housing, are taking on steadily greater legal significance. There are pushes these days in Sacramento, such as Scott Wiener’s “streamlined approval process” bill (SB-35), which are meant to make RHNA quotas mandatory by reducing local control over development decisions. Wiener’s bill would make certain project approvals automatic in cities that have not met their assigned RHNA quotas.

Perhaps this anti-democratic push at the state level might be justified if, in fact, the RHNA quotas were designed to protect and enhance the public welfare. Alas, they are not.

I think if more policy-makers discussed what the RHNA math and maps imply, our local housing policies might be very different.

RHNA, looked at carefully, is a pro-displacement, pro-gentrification policy which — by design — will permanently destabilize low-income community in the Bay Area. I’ll explain how, with particular attention to the example of Berkeley.

In the short term, the RHNA demands that the most affordable parts of the region become less affordable. Let’s consider the case of Berkeley:

Using Census Bureau data (from the American Community Survey), ABAG determined that, around 2009, about 32% of Berkeley’s households were “very low income” (or below), compared to the Area Median Income.

ABAG also found that in the region as a whole, only about 24% of households were “very low income.”

Because Berkeley currently has a larger share of very low income households than the region as a whole, ABAG demands that Berkeley build:

- A disproportionately large number (47%) of housing units for “Above Moderate” (i.e. high income) households.

- A disproportionately small number (18%) of units affordable to very low income households.

What does this imply? First, if not a single household were displaced while Berkeley achieved its RHNA allocations, Berkeley would nevertheless become less affordable. Second, in reality, displacement is occurring at a fast rate, and ABAG demands that Berkeley try to provide greater options for high income households, and fewer options for very low income households.

In the short term, Berkeley’s loss of very low income households is ABAG’s plan functioning as explicitly intended.

From the Regional Housing Need Plan, San Francisco Bay Area, 2014-2022:

Allocating a lower proportion of housing need to an income category when a jurisdiction already has a disproportionately high share of households in that income category, as compared to the countywide distribution of households in that category from the most recent decennial United States census. The income allocation method compares each jurisdiction’s household income distribution to the regionwide household distribution, based on data from the US Census 2005-2009 American Community Survey. A jurisdiction that has a relatively higher proportion of households in a certain income category receives a smaller allocation of housing units in that same category. For example, jurisdictions that already supply a large amount of affordable housing receive lower affordable housing allocations. This promotes the state objective for reducing concentrations of poverty and increasing the mix of housing types among cities and counties equitably.

Berkeley is steadily losing existing affordable housing units through a mix of rapid turnover in rent-stabilized units, loss of rent-stabilized units, and loss or turnover of other units with historically low rents or low owner-occupant expenses. Following ABAG and Sacramento, Berkeley has wholeheartedly embraced the strategy of income-restricted housing.

I see a problem with that.

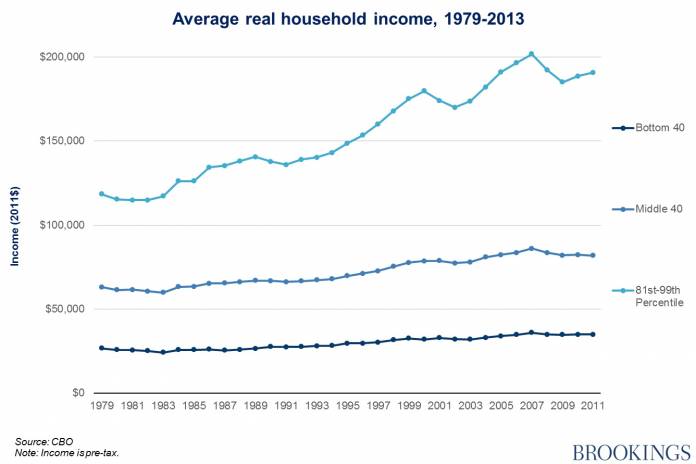

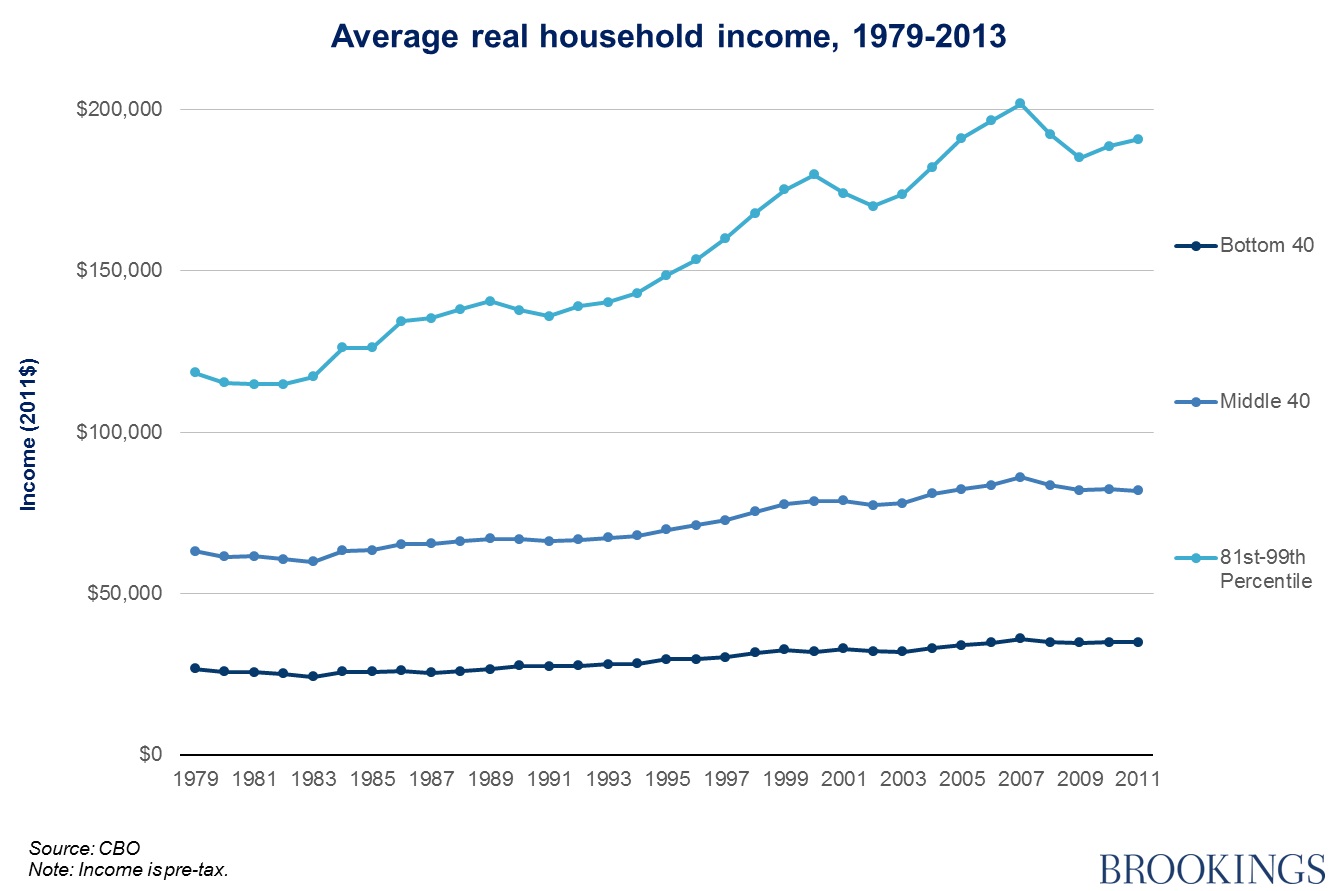

For decades, wage growth has followed this pattern: The income of high income households increases much faster than the income of middle income households. The income of middle income households increases somewhat faster than the income of low income households.

As a consequence, over time the rise in the median income moves many moderate income households to the lower income category, and many lower income households to the very low income category.

The number of income-restricted housing units available for each category is not changed by that change in incomes, but the range of incomes in each category change. For example, the upper limit on incomes that qualify for very low income housing rises, and it rises faster than the incomes of households currently in those units.

Even though income-restricted units are allocated randomly among qualified applications (i.e. by lottery), the tendency over time will be for competition for very low and low income units to grow, faster than new units can be created.

The odds that a displaced income-restricted person can relocate within the region, never mind her local community, will continually fall.

Every step of the way, politicians who are unconcerned about that human reality will be able to point to the large pool of income-restricted units. They can say — following the dubious method of measurement used by the UC Berkeley Anti-Displacement Project — that displacement has not taken place because the percentage of poor people remains the same, even though poor households are constantly being expelled from the region and replaced with newly poor but higher-income households.

Here is a straw-man policy proposal. It is not meant as a fully worked policy. It is not meant to convince you such a policy is definitely possible. It is a just a way to point out that there MAY be better options.

Instead of income-restricted units, Berkeley could emphasize the need to grow a large pool of social housing whose rents could be flexibly determined, such as through means-testing.

Social housing does not have to mean “housing projects” meant solely for poor people. Social housing can be available, in various degrees, even to high income households – households whose rents then subsidize very low income households as necessary.

Such a system could help to stabilize communities. It could help foster economic growth that rises from the community rather than growth which is alien to and imposed upon the community.

Whether social housing is the future or not, though, the ABAG plan is a recipe for permanent displacement, always putting capital ahead of community.

Thomas Lord abides in Berkeley, for some reason.

“no one is making the argument that development doesn’t increase displacement on a neighborhood or block level”

Then I’ll make that argument. Housing development doesn’t increase residential displacement on a neighborhood or block level. The Urban Displacement Project at UC Berkeley explicitly tested the hypothesis that market-rate housing increased block-group-level displacement, and found no connection. See http://www.urbandisplacement.org/sites/default/files/images/udp_research_brief_052316.pdf, page 7: “Comparing the effect of market-rate and subsidized housing at [the block group level], we find that neither the development of market-rate nor subsidized housing has a significant impact on displacement.”

No matter how many times slow-growthers repeat the claim that market-rate housing development increases residential displacement, it remains false.

My favorite recent entry in the bullshit economics category is the recent paper co-authored by a guy from Cal (UC Berkeley) that YIMBYs and partisan journalists are mis-characterizing as proving that zoning has cut GDP in half over the past 50 years or so. Where do you even begin trying to unravel that kind of rubbish? At least the promoters of such headlines turn out to be pretty woolly-minded if you get them talking, amIright Dirty Burrito?

Here’s a video for you:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PtBy_ppG4hY

1. Sorry, I should have said “wtf does being bombed in WWII have to do with the high rate of housing production in Tokyo?”

2. Regarding the data from the PDF, you are correct, I misinterpreted the meaning of those numbers. That doesn’t change my view that per-unit land costs, which account for the bulk of housing costs, can be drastically reduced.

3. “You have implied, in this context, that building a much larger number of units per unit of land will be sufficiently profitable as to motivate investors to build decent housing for lower income households.”

I didn’t mean to imply that. There will always be a segment of the population that the market will not build for, the problem right now is that segment of the population is very large.

4. You have assumed that land use reform in San Francisco would be sufficient to eliminate the scarcity of land relative to demand.

Not the scarcity of land, the scarcity of housing relative to demand. More on this:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228180251_Zoning's_Steep_Price

Anyway, I’m tired of talking to you, you’re tired of talking to me, so I’ll leave you with a nice video.

“How an Average Family in Tokyo Can Buy a New Home” (detached)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iGbC5j4pG9w

Why are you talking about “ability to build housing”? What the heck is “ability” to build housing in this context?

Honestly, you seem like you have no argument but stubbornly persist.

(Aside: if you edit your comment and get rid of the bogus newlines, it will be much easier to read.)

Your misunderstanding is not just getting that one dollar amount wrong. You misunderstand the logical structure of Glaeser’s argument there.

Glaeser compares San Francisco to an idealized market in which land offered up for development is plentiful, and regulation imposes little cost above that. Glaeser notes that construction in hilly San Francisco is more difficult than construction on flat, open land and tries to take that into account. On the basis of this comparison, Glaeser reaches a conclusion that should surprise absolutely nobody:

Buying land for development in San Francisco is very, very expensive and this tends to drive up the cost of producing new units of housing there.

Yes, a similar theorem is proved more simply in The Big Book of D’uh, No Kidding, but Glaeser has formalized what was already obvious.

What Glaeser does not and can not show is that the price premium on land is caused by the land use regulatory regime. For example, he explicitly makes no attempt to rule out alternative hypotheses such as that the tighter regulation and the land scarcity have some third cause(s) in common. (See page 9 beginning with “With respect to the implications…”)

Your original statement — which is false — is:

That is your, not their conclusion, and to reach that conclusion you have snuck in at least one additional assumptions:

1. You have assumed that land use reform in San Francisco would be sufficient to eliminate the scarcity of land relative to demand. This assumption disregards private options to constrain that supply, and disregards the legal, political, geographic, and technological limits of reform.

Really, I think you make a second assumption, or at

2. You have implied, in this context, that building a much larger number of units per unit of land will be sufficiently profitable as to motivate investors to build decent housing for lower income households. That is an entirely unsupported view, though. It is contradicted by the real situation in countless cities. It is contradicted by Patrick Kennedy’s micro-unit offer to Berkeley. It is a problem that Glaeser et al., repeatedly, decline to even take up — hence their concern with affordability-of-new-construction, not affordability-of-tenancy (see the discussion of this in the introduction to the paper).

You have a short memory.

You said Tokyo has a “political history” that is “vast, complicated and unique,” and then pointed specifically to the bombing of Tokyo as one of the differences that could account for their housing production.

I then pointed to London as an example of a dense city that has been bombed like Tokyo, and does not have a high level of housing production.

The point is having being bombed 70 years ago should have nothing to do with the ability to build housing.

“This article is about the RHNA in this region.”

We haven’t been talking about your article for a while now. RHNA is not zoning reform.

That sounds like your misunderstanding of that paper.

You’re right, the difference is not $533k, it’s $441,765.

“San Francisco is a relatively high physical construction cost market, but that is not what makes

its homes cost so much. The self-reported price associated with the median price-to-cost ratio in

this market in 2013 is $800,000. That HP/MPPC=2.84 implies minimum profitable production

costs of $281,690. Using the fact that MPPC=1.46*CC from Section II, we can further impute

16

that physical construction costs for this unit were $192,938.

25 That leaves a ‘free market’ land

price of $48,235. Stated differently, that is what we think the underlying land would cost in a

relatively unregulated residential development market. Land and structure costs sum to

$241,173 for this unit and the builder’s 17% gross margin makes up the rest to get to $281,690.

Because the scarce factor is land, not building materials or construction labor, what makes San

Francisco housing so expensive is the bidding up of land values. Developers cannot actually

earn super-normal profits on the margin. Our formula suggests that the land underlying this

particular modest quality house cost about $490,000—roughly 10 times the amount presumed for

MPPC calculations.26 ”

http://realestate.wharton.upenn.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/802.pdf

As we are looking at the snarled traffic, and considering the why’s of blended water, one must question what kind of lifestyles we are giving up and what quality of life we will have if we are forced to “take” more people and cram them into this small plot of land instead of spreading out a bit so we can appreciate our life and our air, and our water, and maybe even preserve a few views, that brought us here in the first place.

This article is about the RHNA in this region.

That sounds like your misunderstanding of that paper. Incidentally, that paper doesn’t address any of the issues raised in this 48hills article.

Also, it’s spelled “Glaeser”.

And? Connect the dots here. Your thesis is that if London had land use policies like Tokyo, that the supply functions for new housing would be the same in Tokyo and London?

This is your thesis?

(And it relates to displacement and gentrification, how?)

jim hoch, why do you take such cheap shots like that? You know I didn’t say this:

What kind of position is YIMBYism that you have to lie, so? Your position is that weak? Why do you bother, then?

What I said … here, let’s just take a look:

You can pretend not see the difference between what I said and your cheap shot, but you can’t fool people.

So if people from Ohio and Texas are not part of the community then we should deport people who come from even further away, such as Mexico, Haiti or South America?

So had London.

And now the Tokyo metropolis manages to out-build all of England with just 1/4th the population and 1/60th of the land.

“The zoning reforms typically suggested would raise land prices and somewhat lower regulatory costs.”

What’s important is per-unit land costs, not absolute. Also, I’m not talking about ” zoning reforms typically suggested,” I’m talking about Tokyo style land use regulation.

“The fact that current new production is already at through-the-roof market prices mean that per unit costs would have to plummet to see significant new development. ”

Much of that per-unit cost is land, very roughly 70% in places like San Francisco and Tokyo. Construction costs can only be lowered by building smaller units or using lower quality finishes, but per-unit land costs are highly malleable.

What you’re not accounting for is the fact that land costs can be spread over a number of units, and the per-unit land cost can be lowered by increasing zoning density. E.g. in Land prices in the suburbs of Burnaby (Vancouver) and Edogawa (Tokyo) are comparable, but lots in Tokyo are a fraction of the size of the lots in Vancouver, and the cost of a single family home is proportionally lower. In Tokyo you are free to subdivide your single family home lot and build 2 or more single family homes where there was only one before, and people frequently do.

Glaser and Gyourko estimate land use reform in San Francisco could lower per-unit land costs by $533k, based on 2013 prices (http://realestate.wharton.upenn.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/802.pdf)This mechanism of lowering per-unit land costs, while not intuitive, is central to the YIMBY argument.

Talk about strawman! When I asked for details, I’m looking for textual evidence (i.e., the RHNA requires x, therefore Berkeley has to do y), not more non sequiturs and exaggerations.

I’ve yet to meet a YIMBY who can recognize a supply and demand argument when they see one.

My argument IS based on the laws of supply and demand.

We have, today, a certain level of production in reaction to market prices and their trends. The supply is famously, relatively, inelastic relative to changes in market price.

The zoning reforms typically suggested would raise land prices and somewhat lower regulatory costs. The difference between those two (if there is, indeed, any), when amortized over a few decades, is a good estimate of the maximum reduction in market price still consistent with new production. The fact that current new production is already at through-the-roof market prices mean that per unit costs would have to plummet to see significant new development. Zoning reform won’t do that.

What will YIMBY zoning reform do? Well, in its “urbanist”, RHNA, disperse-the-poors form it will lead to small increments of new housing production, largely at the cost of displacing those communities that can be displaced the cheapest — people on the poorer end of the spectrum.

By 1945, most of Tokyo had been destroyed by bombs.

In essence you insinuated it’s impossible for the market to produce that much housing, and I pointed to a place where it’s actually happening.

When confronted with that evidence you then pointed to “political history” that is “vast, complicated and unique,” as if there is something magical and irreproducible about Japan’s ability to produce housing.

Tokyo has a similar per-capita GDP and a similar population growth rate compared to the Bay Area. They are much denser than us so it should be more expensive to produce housing, yet per-capita housing production is 5x higher, and market rate prices are substantially lower. Additionally, home buyers in Japan have access to 1.25% fixed rate mortgages, which should put additional upward pressure on prices relative to the bay area.

“if you are allowed that ridiculous move, why then you can prove from your assumption that land use regulation accounts for all the difference.”

How is zoning reform ridiculous?

We’ve already performed the NIMBY social experiment in which little gets built and long time landlords and homeowners reap out-sized economic rewards, and housing costs are now among the highest in the world. I don’t see how it’s ridiculous to try something else.

“YIMBYs, one must conclude, believe in the laws of supply and demand when it suits them, and reject them when they do not.”

The only people I’ve encountered who reject supply and demand are anti-growth activists.

Translation: “You propose a solution but I want to proceed as if you had not so I say it doesn’t count.”

As the article says, production of social housing includes market rate production. The question you should ask is to where should the profit of market rate housing be directed, to which I have answered: All of it should go towards the production of social housing.

I see people making arguments against the “ABAG” housing quotas as a veiled argument against more market rate housing development. You raise what you see as a problem, but then propose no solutions (well, one, but more as a possiblity). In your future ideal, what do you see as the role of new market rate development?

Yes, and as the article points out, the RHNA is designed to make that kind of thing permanent and normal.

This past weekend, there was a lottery for 32 affordable units in Alameda, 12,000 people applied. That means that 11968 people will continue to live in market rate units that they struggle to afford. Ignoring the “market rate” helps no one but land owners.

Here, “Dirty Burrito” (suitably anonymous), you give a fine example of YIMBY party pseudo-scientific lies.

The political history that produced modern Tokyo is vast, complicated, and unique. You reduce that history to nothing more than land use regulation for the sole reason that if you are allowed that ridiculous move, why then you can prove from your assumption that land use regulation accounts for all the difference.

YIMBYs, one must conclude, believe in the laws of supply and demand when it suits them, and reject them when they do not. Or else, alternatively, perhaps they simply don’t understand those laws.

” Speculative development will not produce that much housing because it would require investors to make facially stupid investments.”

If that’s true, please explain how Tokyo produces 28 times a much housing as the San Francisco–Oakland–Hayward Metropolitan Statistical Area, in one third the space?

Data:

https://www.ft.com/content/023562e2-54a6-11e6-befd-2fc0c26b3c60

https://www.curbed.com/2016/2/24/11102278/bay-area-housing-crisis-bubble

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/San_Francisco%E2%80%93Oakland%E2%80%93Hayward,_CA_Metropolitan_Statistical_Area

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tokyo

“The state has no policy lever to compel speculative development to produce that much housing. ”

It does, and it’s called zoning reform. I’m sure you’re aware of the 2002 urban renaissance law in Japan.

“The profitable development that YIMBY policies do bring about is displacement from and redevelopment of neighborhoods with concentrations of lower income households. ”

Right, like the “Apartments at Deer Hill” in that ghetto known as Lafayette, that were the subject of a lawsuit brought by sfbarf.

The “ghetto clearing” you are referencing is due to middle income people buying houses in the poorest areas, because they can no longer afford to buy anywhere else. This is the direct consequence of a lack of inventory, not some developer plot to cleanse the ghettos. If you’re looking for someone to blame, look in the mirror.

“To combat displacement, and promote community welfare, government’s option is to act directly, both by intensifying anti-displacement protections, and by expanding the supply of social housing.”

Hong Kong took this path and they are now 49%+ public housing. My understanding is housing consumes a very high percentage of income for both market rate and public housing occupants.

It’s pseudo-scientific rubbish. It has enough fudge factors that its outcome is almost entirely political.

Your alternative is to use the violence of the state to force out the people you’ve decided should not reproduce based on their wages. Own that.

Jim, where I live in Berkeley, the community contains lots of kids who are growing up together, a lot of lower-wage working people (including their moms and dads) who support each other in various ways, some elders providing social anchors, a lot of built-up social capital about how to deal with petty crime and more serious crime, annual traditions, mutual understandings, some shared projects, multiple-generations of history (some remembered even on a national or international scale) and so on. It’s like that for miles in some directions. And yet… Nearly every family and household in my immediate area is one set-back away from displacement from the region. The community as a whole is in a precarious state.

Sometimes some YIMBY partisans tell me my community — the people I just described — is rich and selfish and that we should think about giving up hour homes to make room for the burning hoards from Ohio and Texas who are “displaced” from their desire to take over this neighborhood. No, I don’t think those theorized migrants are part of any community here. They are an abstract demographic category, used for propaganda purposes, based on vulgar economic superstitions. They are a weapon of cynical speculators.

The current housing crisis is engineered. The same capitalists who bloat the payrolls of tech firms capture those burn rates on the back end with their shares in real estate trusts and personal holdings. It’s the same scheme their predecessors started running more than a century ago, the main difference in the modern age being that they’ve pretty much run out of undeveloped land around the Bay.

The state has no policy lever to compel speculative development to produce that much housing. Speculative development will not produce that much housing because it would require investors to make facially stupid investments.

The profitable development that YIMBY policies do bring about is displacement from and redevelopment of neighborhoods with concentrations of lower income households. That is why many “priority development areas” attack lower income and often less white neighborhoods. It is also why speculators by up large inventories of distressed lower-income housing. It is nothing but ghetto clearing by a new name.

To combat displacement, and promote community welfare, government’s option is to act directly, both by intensifying anti-displacement protections, and by expanding the supply of social housing.

You’re right that the RHNA extrapolation and allocation process is somewhat hard to follow, but it still mostly fits on a few spreadsheets. It does not use particularly complicated economic and greenhouse gas models, like Plan Bay Area does for example.

Can and should “native” residents have a greater right than migrants to form a family in the Bay Area? Practically speaking, in the housing market, when we make housing unattainable to migrants, it also makes housing unaffordable to the families who grew up here.

Supporting the construction of low income affordable housing, as you are, does not make one a non-segregationist.

If, like Zelda, you oppose development on the scale that can make a real impact on market rate prices, a scale that prevents white, middle class San Franciscans from bidding up the last bits of affordable property in East Oakland, then you are promoting displacement and economic segregation on a grand scale.

Creating a few thousand units of affordable housing when you’re short 100k units per year does not even begin to make up the difference. It’s the equivalent of Donald Trump slashing the NPS budget by $1.5B, then donating $78k of his own money to make up for it. Worse yet, you’re the guy on Fox news vigorously arguing which parks are most deserving of Trumps donated salary.

So people who might rent or buy market rate housing are not part of “the public”? They are also not part of the “community” either?

“if, in fact, the RHNA quotas were designed to protect and enhance the public welfare. Alas, they are not.

Many segregationists are not as frank as you.

I would again refer you to the article. (Did you read it?)

What these cities are planning is a permanent destabilization of lower income communities.

Misc. replies:

For example, the assumptions:

1. that land use policy interventions can cause private sector housing production to yield planned quantities of housing and housing in certain planned ratios of affordability.

2. that it is equitable to promote the dissolution and dispersal of concentrations of lower income households.

These land use policy interventions can’t cause the quantity and quality of development “planned”, but they can accelerate land-grabs out from under lower income communities.

Great. Population growth is dependent on much more than housing production. For example, it depends on the relative attractiveness of labor demand in various parts of the world.

While you paint a sentimental picture, it is not an accurate statement of the purpose of the legislation.

Even if it were, no change in land use regulation would cause that level of new housing development to become sufficiently profitable.

It is part of my role in Berkeley to help develop housing policy which promotes housing affordability and helps to prevent people from becoming homeless. Protecting existing community, especially existing lower income households, is critical to such policies. The RHNA, in my view, in practice, is an obstacle — an attack on housing affordability.

As discussed in the article.

Without downzoning of vulnerable neighborhoods, upzoning the hills will have little impact. It is more profitable to buy and redevelop cheaper land, distressed properties, rent stabilized stock, and so on.

Redevelopment has always been about dispersing lower income communities.

It is not a shortage permits that is cause the lack of housing affordable at and below the median area income.

Look, no one is making the argument that development doesn’t increase displacement on a neighborhood or block level. The only argument is development puts downward pressure on housing prices regionally (eg bay area).

“State projections of population growth are aspirational in nature”

Regardless, the population is growing much faster than the housing supply

i wonder if Berkeley is a good example for assessing the number of lower income households. Berkeley has a large student population and recent graduates whose incomes are “naturally” lower. Many are aspirational and individually improve their relative income standing over time. Most of them consider their housing temporary and live in increased density, e.g. sharing units or bedrooms in a communal fashion. Those households compositions are continually changing and shouldn’t really be considered in this discussion other than by the institutions they attend that have an obligation to support their housing needs.

Seems to me that delving into and addressing the reasons for growing income inequality and reducing it is much more important than simply assuming “the poor are always with us” and build for that. If income inequality is unaddressed and keeps growing along with total population, housing will be the least of the social problems as poverty will have no floor and the 25-40 percentile will look wealthy to the 10-25 percentile.

You write: “But the goal of the RHNA is pretty straightforward: California intends to accommodate the children who grow up here and the net migration at the historical rate. If we do not permit at least enough housing for the kids who are already in high school and college now, then we are guaranteed to have displacement.”

First, there’s nothing straightforward about the calculations behind the RHNAS, as demonstrated by the attached document from ABAG.

But the goal of the RHNA is pretty straightforward: California intends to accommodate the children who grow up here and the net migration at the historical rate. If we do not permit at least enough housing for the kids who are already in high school and college now, then we are guaranteed to have displacement.

http://abag.ca.gov/planning/housingneeds/

Secondly, it’s one thing to talk about housing current residents and their descendants and quite another to talk about housing prospective migrants. How can not accommodating people who don’t live here foster displacement?

Again, the essential thrust of SB 35 is putting legal teeth into the RHNAs–a profound change in state housing law. Had Wiener openly declared his intention to pursue that change if he got into the State Senate, you can be sure that would have become a hot topic in his race with Jane Kim. Not only did he stay mum; as I reported, he ignored my query to him, posed after his election but before his swearing-in, as to whether he intended to follow just that course.

Sorry, I don’t understand; what assumptions about capital are in the Housing Element law?

To some degree, this is true; population growth in the region is dependent on housing production, and in the private housing market there is no way to ensure that the newly constructed housing goes to the populations that the Housing Element intends to zone for.But the goal of the RHNA is pretty straightforward: California intends to accommodate the children who grow up here and the net migration at the historical rate. If we do not permit at least enough housing for the kids who are already in high school and college now, then we are guaranteed to have displacement.Personally I would support the RHNA until someone proposes a better alternative.

No insult was implied.

Again, is there any specific way that the above moderate income quota hurts Berkeley? Where in the law does the RHNA compel the destruction of communities? And couldn’t Berkeley decide to upzone the hills instead of downtown?

Integration has never been about dispersing toxic objects. And you didn’t answer the question. Do you think it is proper policy to require higher-income cities to plan for more low income housing growth?

I get that you think Berkeley should provide more low income housing. Great! Let’s imagine that Berkeley were to permit more than its fair share of very low, low, and moderate income housing and zero above moderate income housing, with the sum of housing permits equal to the total RHNA target. Would the state Housing Element law prevent them from doing this? I don’t think so, but I’m willing to read any evidence you have. Do you know of some way that any action under state law could be brought against Berkeley in such a scenario?

Sorry, I meant that decisions such as the identification of PDAs (such as the San Francisco’s PDAs which you identified as being approved by the BoS earlier) and the identification of housing sites in the Housing Element.

I’m sorry, I don’t follow. Wiener’s SB 35 streamlining is more restrictive than Brown’s Trailer Bill 707. If Wiener supported (with amendments) the governor’s bill that would have allowed streamlining in every city, how is it deceptive that his own bill allows streamlining in those cities that have not met their RHNA?

“Perhaps ABAG and MTC policies are complicated enough that they warrant separate elections and staff, but their land use decisions still have to be negotiated and approved by their respective city councils.”

Really? That’s news to me. Please document such approval.

Wiener’s votes at the BoS on housing streamlining do not equate with making the Regional Housing Needs Allocations legally enforceable. On this issue, he ran a devious campaign.

First, thank you for reporting on this issue because I do agree that whatever happens with Plan Bay Area is important for the health of our region. I would counter that the people most left out of the process are the commuters that have no vote in the cities where they work. For people who cross two bridges to get to work, their only representation for land use decisions near work is at ABAG, MTC, and the state legislature. For commuters, ABAG and the MTC are more democratic than Silicon Valley city councils. See Alon Levy’s blog post on commuter disenfranchisement for more on this argument.

This is one of the challenges of government. I don’t get to vote directly for any number of commissions or committees that my elected officials sit on or appoint members to. Perhaps ABAG and MTC policies are complicated enough that they warrant separate elections and staff, but their land use decisions still have to be negotiated and approved by their respective city councils. I don’t think this is reason enough to call Plan Bay Area “un-democratic,” any more so than we would introduce the Supreme Court or United Nations as un-democratic. If you are proposing some reform that involves direct election to the council of governments, I may support that.

Scott Wiener’s work at the MTC and his position on housing streamlining were clear prior to the 2016 election (as evidenced by the BoS hearings on the resolutions by Peskin against the Governor’s streamlining bill and by Wiener in favor of streamlining), which Tim Redmond reported on briefly. Wiener’s and Jane Kim’s positions on housing were absolutely factors that I considered when voting.

While this article does not dive deeply into the question (because it is a large topic), I would argue that California’s housing element law is fatally flawed, based on false premises about the state’s capacity to manage capital.

State projections of population growth are aspirational in nature and the rationales given for them are pseudo-science.

It is cheap of you to argue by association though there is no insult in being compared to Ms. Bronstein.

Your strawman (“all state laws are anti-democratic”) is equally offensive.

State housing law is increasingly making mandatory the forcible destruction and dispersal of real existing communities. The rationales for this intervention lie first in prioritizing capital over people, and second in false theories of the state’s relation to capital. Consequently, state housing law is nothing but a corrupt cesspool of political wrangling over land-grabs out from under real existing communities.

No wonder you have only such cheap rhetorical tactics to defend it.

And? The people in the neighborhoods being crushed by these laws happen to want more housing but housing that will allow the existing community to expand rather than to be pushed out.

You propose that one place is as good as another and that the commodity category of low income household is an object — slightly toxic — to be dispersed as thinly over the region as possible. How utterly inhumane of you.

The housing element system should be thrown out.

The article names some. Have you read it?

The legal regime of so-called afforcable units that are income restricted to a range tied to area median income is a nation-wide scheme.

And he calls surrounding bills “anti-democratic” without any explanation (echoing Zelda Bronstein). Does Thomas Lord think all state laws are anti-democratic because they preempt local laws?

My criticism of Plan Bay Area as un-democratic in the story to which you link has plenty of explanation. The problem is not that this so-called blue-print is mandated by state law (SB 375), but first, as I reported, that its provisions have never been vetted by the people whose lives it most directly impacts: the residents of the neighborhoods designated as Priority Development Areas.

Secondly, the officials approving PBA are not elected to their positions on MTC and ABAG; they are (mostly) city councilmembers and county supervisors. They have no regional staff. They have all they can handle governing their respective jurisdictions. If the citizens of a Bay Area city don’t like the actions these officials take in their regional capacities, they have no redress.

When Scott Wiener ran for State Senate, he said nothing about putting legal teeth into the RHNAs. Yet hours after he was sworn into his new office, he introduced SB 35, which would do just that. This would be a major change in state housing law. Clearly he knew he was going to push it; he should have said so during his campaign.

And he calls surrounding bills “anti-democratic” without any explanation (echoing Zelda Bronstein). Does Thomas Lord think all state laws are anti-democratic because they preempt local laws?

My criticism of Plan Bay Area as undemocratic, set forth in the story to which you link, has plenty of explanation. To wit, the problem isn’t that this so-called blueprint is mandated by a state law (SB 375), but that its provisions have never been vetted by the people whose lives it will directly affect. As I reported, the Priority Development Areas in San Francisco were approved by the Board of Supervisors in 2007 without any consultation with the affected neighborhoods. Ditto for the humongous growth forecasts for San Francisco as a whole and for each PDA in PBA 2040.

When Scott Wiener ran for the State Senate, he never indicated that he was going to sponsor legislation that would make the RHNAs legally enforceable. Nevertheless, only a few hours after he was sworn into office, he introduced SB 35, which will do exactly that. This would be a major change in state housing law. Clearly Wiener knew he was going to push it; he should have said so during his campaign.

Housing is a human right. Period. A whole slew of social problems are ameliorated when people have access to safe, guaranteed housing. In addition, ALL housing should be affordable housing. Rent/mortgage pimping is theft. Even if someone is working for a big company and earning a fat salary, how much more money would that person be spending locally, and in general for services, amenities, hobbies, products, a business of their own, if they were not forking a hefty part of their salary for an (alleged) “luxury” apartment? ? Profits from real property do not benefit communities and, as is quite clear, tend to destroy them. The real estate developer investment class commits violence on the community in their pursuit of profits, particularly considering the shoddy craftsmanship, and poor management of most new multi-unit buildings. People are displaced, communities destabilized, palms greased.

I’m not sure what Thomas Lord is getting at here. He uses a lot of phrases which need clarification and evidence. And it’s not clear how much of his criticisms are directed against the 1980 Housing Element Law in general, or specifically against the Sustainable Communities Strategy (2008 SB 375, Steinberg) or local inclusionary housing ordinances.For example, he says the RHNA is “erroneously called a city’s ‘fair share’.” Does he only object to the income share details? Does he also take issue with the concept of dividing population growth among cities? And he calls surrounding bills “anti-democratic” without any explanation (echoing Zelda Bronstein). Does Thomas Lord think all state laws are anti-democratic because they preempt local laws?

Yes, it’s true that the RHNA allocates housing shares in inverse proportion to the existing income distribution (see the spreadsheet under Additional Resources Gov. Code §65584(d)(4)). So while Berkeley is not expected to produce as many low and very low income housing units, other cities such as Pleasanton and Palo Alto receive a greater RHNA allocation of low and very low income housing units.Is Thomas suggesting that the allocation should not put more of the low-income quota in high-income cities? What is his preferred alternative?Is there any specific way that the relatively higher above moderate income quota hurts Berkeley’s Housing Element or policy? I should note that the RHNA strengthening bills, SB-35, Wiener and SB 167, Skinner, do not do anything to enforce the above moderate income quota. They only compel cities that have not met their very low, low, and moderate income fair share to approve more.The rest of the complaints appear to be with Berkeley’s local inclusionary housing policy, not something that the RHNA forces. If it wanted, Berkeley could produce more low-income housing or rent-stabilized housing than is required by the RHNA, so I’m not seeing any objection to the RHNA there.I agree that there are problems with the Housing Element Law, but I think the problem is the opposite of Thomas Lord’s complaints. The problem is that the Housing Element is not strong enough. Thomas’s quote, “the tendency over time will be for competition for very low and low income units to grow, faster than new units can be created,” applies not only to low-income households but also households of all incomes. Even Tim Redmond and Fernando Martí and Peter Cohen of CCHO have gone so far as to state the need for wealthy cities to do their fair share of housing production (although they don’t seem to support the proposals on the table). The RHNA should translate to unit construction (SB 35). The Anti-NIMBY Housing Accountability Act should be enforceable (SB 167). And Housing Elements should include a low income feasibility analysis.

Not that I know of. The City of Vancouver has made two small experiments of this sort. One is a pool of social housing built decades ago and generally considered to be a success. The other is brand new.

No, that’s not correct. Because social housing can yield a net income, it can be self-funding. Governments role is to facilitate and help finance it (by enabling private investment in social housing). Even the financing, since it is backed by a real asset, will carry little risk to the public.

You answered my question below. Social housing is public housing. The government builds the housing with tax money.

Is there anyplace in the Bay Area where the third way exists and who is the landlord or owner?

We have some sense of the level of displacement based on quantitative facts like rates of known evictions and foreclosures, and from qualitative facts like the changes over time in the case loads seen by housing counselors both at the Rent Stabilization Board and at some of our non-government organizations.

Berkeley makes it difficult to demolish existing rent stabilized housing and even so, we have seen demolition-by-neglect used to accomplish that aim.

Throughout the Bay Area there is publicly owned housing which is exclusively reserved for lower income households. I think that in every case this older form of public housing is reliant on subsidy in the form of welfare transfers from local, state, and federal government. This form of public housing — needlessly limited to lower income households — is expensive to provide and is a permanent financial liability.

The current system of requiring “inclusionary units” or mitigation fees is itself a system of using higher-rent tenancies to fund the creation of lower rent units. The problem is that this system, based on private ownership, is incapable of meeting the need AND it is expensive for cities to monitor. Only a tiny fraction of the net income goes towards housing affordability, and even that fraction requires a regulatory overhead.

The third way — social housing that includes higher rent units — has the potential for being financially efficient, self-funding, and not reliant on welfare transfers from local, state, and federal government.

Currently there are lots along commercial corridors that can be developed not impacted much by regulation or neighbors. I am thinking of that 3 stories over retail building across from Safeway on Taraval. Why is that not happening more.

I understand that tearing down existing housing causes displacement. I was thinking of SF where it is often a commercial building or an empty lot where there is new development. How is displacement in Berkeley measured. Is it from existing buildings being torn down?

So the higher income tenants pay extra for the lower income tenants? What does the cost of the unit mean? Is there anyplace in the Bay Area where social housing exists?

One point of “social housing” is that it is NOT exclusively for low income households. It can include units leased at or close to market rates. Net income from such units can cross subsidize housing costs for very low income households.

Households that may be legally recognized as “low income” — e.g., 80% of the area median income — don’t necessarily need a subsidy. Even if their rent is below market, they are still often able to pay a rent that exceeds the costs of their unit, yielding a net income to the public which can be used to subsidize poorer households, and/or expand the supply of social housing.

No, I don’t think it is an apt comparison. By “social housing” I mean simply housing which is publicly owned.

Consolidating ownership with the public means that rent prices can be set by policy. It also means that properties can cross-subsidize more easily (e.g., net income from high rent tenants paying upkeep costs for extremely low rent units).

1960s communes tended to be individually owned and autonomously run by residents. That is nothing more than private ownership property with a non-traditional household composition. It yields no particular public benefit of housing affordability.

Don’t buy into YIMBY strawmen:

In the article I make two arguments:

1. That development which destroys existing low income housing causes displacement directly, from those units which are destroyed.

2. That displacement is occurring (for any reason) at a very high rate, but the ABAG quotas tell Berkeley, which is experiencing considerable displacement, to build a reduced percentage of affordable units. ABAG has told Berkeley to further gentrify.

I do happen to believe that network effects also link some new development to displacement in the immediate vicinity, but that is not an argument I made in this essay.

The problem is not “compelling” developers to develop, its “allowing” developers to develop. Too many onerous regulations and cranky home owners preventing sensible density near transit.

Nothing is preventing them from doing anything, they have the choice to do what they want within reason. I fail to see this as any type of concern at all. If you’re worried about taxes, well, on average the millionaire home owners likely don’t pay anything significant due to their prop 13 deals. Replacing Becky O’Malley with someone who makes 50k per year would likely increase the tax base in the city LOL.

What is to prevent the millionaire homeowner class from moving out as the poor move in?

Who is going to subsidize the rents of low income households?

The intent is to get wealthy people to live in poor neighborhoods and get poor people to live in wealthy neighborhoods? Fat chance. Where has that worked? How does State or City require a developer to develop?

I don’t buy the argument that development causes displacement. High rents cause development. Development does not cause high rents.

Social housing reminds me of communes from the 1960’s. Is that a fair comparison?

Agreed! We should upzone all of berkeley and allow affordable housing to be built for all! We’ve given too much power of exclusion to the current millionaire homeowner class!

what is the difference from this and old style redevelopment “slum clearance”?

zoning instead of bulldozers.

market forces instead of eminent domain.

this is flat-out class war.