By Julia Carrie Wong

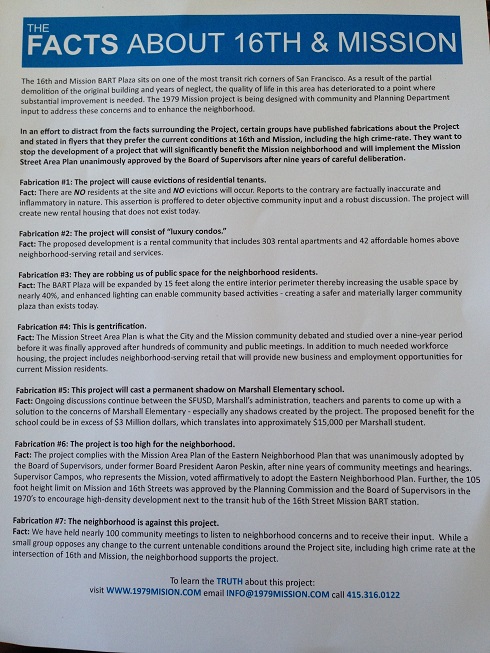

June 15, 2014 — Almost 100 people attended the meeting of the San Francisco Board of Educations’ Buildings, Grounds, and Services Committee Monday night to hear a presentation from Maximus Real Estate Partners on the impact its proposed development at 16th and Mission Streets will have on the adjacent Marshall Elementary School. Conspicuous among the crowd of parents, students, and community activists was the business-casual crew from Maximus. They came armed with a leaflet entitled “The Facts About 16th & Mission” and wearing stickers that read, “1979 Mission Comprometidos con Marshall Elementary” (“1979 Mission is committed to Marshall Elementary”).

But if Maximus’s stickers were intended as a token of good will toward the families of students at Marshall (97% of whom are Latino), the gesture fell flat.

But if Maximus’s stickers were intended as a token of good will toward the families of students at Marshall (97% of whom are Latino), the gesture fell flat.

None of the developer’s written materials came with translation. The presentation was entirely in English. Instead, Spanish speaking parents huddled around organizers from the Plaza 16 Coalition for translation — and expressed all the more anger at Maximus during public comment.

One of the “Fabrications” Maximus intended to debunk in its leaflet was that “The neighborhood is against this project,” but Monday’s meeting provided little evidence of support.

Seth Mallen, the Executive Vice President of Maximus, and Leo Chow, the Skidmore, Owings & Merrill architect for the project, joined David Goldin, the chief facilities officer of San Francisco Unified School District, and Brent Stephens, assistant superintendent, to explain to the School Board commissioners their proposal to mitigate the impacts of the development on the school’s students and facilities.

Maximus intends to enlarge the BART station plaza to allow for storefronts, widen Capp Street’s sidewalk, and fully contain the demolition of existing buildings containing lead and asbestos (“not something that should be scary,” according to Mallen). Chiefly of interest to the school is a proposal to raise Marshall Elementary’s playground a full story. That would lessen the shadows caused by the new residential buildings and create 12,000 square feet of usable space below. Maximus emphasized that its proposal came out of meetings it has held with the “Marshall community,” including teachers, the school administration, and parents.

Mallen said that the cost of the new playground, which could total $3 million, would be borne by the developer. One parent of a Marshall student, Susan Cieutat, suggested that the offer is less than generous, since Maximus could deduct that amount from its mandatory community impact fees. However, Christian Lepley, the spokesperson for Maximus, told me that Maximus does not plan to deduct any of its spending on the school from any impact fees.

Of the dozens of respondents to Maximus’s presentation, the most succinct and adorable were three Marshall students who approached the podium to say, “I don’t need another playground because I already have one, and I like it the way it is.”

Of the dozens of respondents to Maximus’s presentation, the most succinct and adorable were three Marshall students who approached the podium to say, “I don’t need another playground because I already have one, and I like it the way it is.”

Most of the parents who spoke were concerned — not just about the shadow, but about the impact of construction and heavier traffic on their children’s learning environment (the project includes 160 parking spaces). Bianca Guttierez, a mother of two Marshall students, told the commissioners that, although Marshall had been her family’s first-choice school, she would request special dispensation to have her son moved to a new school because she feared the noise and shaking of heavy construction would exacerbate his health problems.

Throughout the evening, a deep level of anger and mistrust was aimed at Maximus. Several speakers said that Maximus is not to be trusted, and alluded to its track record using an investment strategy called “predatory equity.” Opponents of the project raised concerns that the market-rate residential units will lead to further gentrification of the neighborhood and expressed frustration at the developer’s plans to include only 42 affordable units, out of 345 total.

Several parents expressed frustration at those who are outright opposed to Maximus’s project. The current president of the Marshall PTA said, “I think it’s safe to say that all the parents at Marshall wish it weren’t happening, but there’s a group of us that are pragmatic and realistic.” Since the project will be approved, she argued, the best move for parents was to make sure they get the best deal possible from Maximus.

But Maria Zamudio, an organizer from Causa Justa Just Cause, says that this belief in the project’s inevitability is a result of misunderstanding about the process of approvals, fostered by a school administration eager to make a deal. According to Zamudio, many parents thought that Maximus and Marshall were engaging in formal negotiations, that the project had already achieved approval, and that the offer to raise the playground was take-it-or-leave-it. Zamudio told me parents felt pressured by school administrators to support the plan, and that they were told not to pass out flyers for the Plaza 16 Coalition’s community meeting on the project earlier this month.

Concerns about the process were shared by Sandra Lee Fewer, President of the Board of Education. Fewer began the meeting by chastising Maximus, Goldin, and Stephens for holding any kind of talks about school property away from the Board of Education. “Principals do not own school sites and neither do parents,” she said. Instead, the proper body to determine what if any kind of deal can be reached with the school belongs to the board in its role as “the elected, temporary stewards of public land.”

The nearly three-hour meeting did not appear to soften Fewer’s stance. At the end of the night, she dismissed any idea of Maximus’s magnanimity, saying, “I feel like a generous offer would be to build us a whole new school.”