New dance work from David Herrera Performance Company takes personal, tangible approach to immigration issues, April 2-4 at Z Space.

By Marke B.

BAY STAGES The “one step forward, three steps back, push a little, jump way over to the side while Republicans freak out” ritual of our nation’s enraging approach to immigration reform is a dance in itself — featuring rootin’ tooting’ nativists jangling their spurs in a two-faced stomp, while the undocumented duck and weave, often terrified, in and out of the shadows at the back of the stage. (Some bravely rush forward into the light, only to be beaten back by the blows of an implacable bureaucracy.)

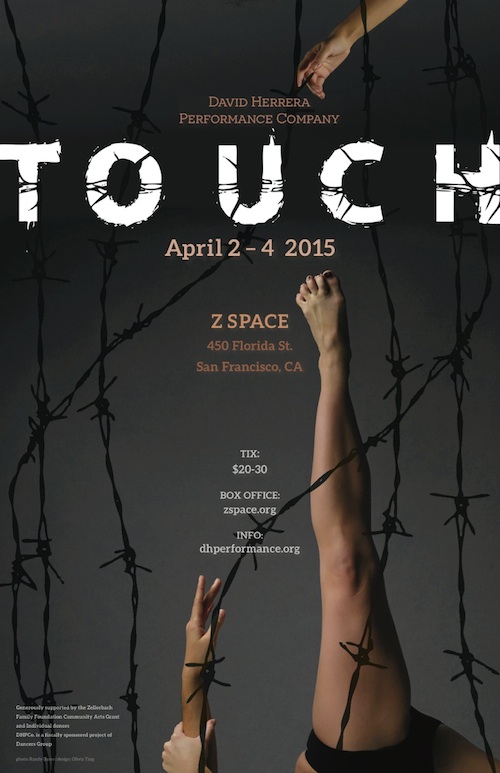

In its seventh season, the ever-sharp David Herrera Performance Company is taking on the frustrating whirl of fear and separation, hope and community with an ambitious new dance piece called “TOUCH”, at Z Space, April 2-4.

“The concept for “TOUCH” is a part of my personal history,” says David Herrera, choreographer and director of the company, which “promotes Latino American voices via modern American movement.”

“My parents were immigrants to the United States and as a family we had several experiences in which border crossings, separation, and fear of deportation were a reality.”

Using intense research and oral history of forced separations, the piece itself is built around a haunting image:

“The inspiration for “TOUCH” came from a particularly striking series of photos of people reuniting at the Mexican/US border fence. In these photos and videos, I noticed one person (presumably on the US side) reaching through the fence.

“That same person was being ‘hugged’ in return by someone on the other side. I thought to myself, whose arms were these? What did this other person look like? How is it they ended up on the other side of the fence? Will this be the only way for tangible connection for these two individuals? Coupled with my personal experience and background I new that I had to bring this situation to the forefront of my art as this part of the immigration story goes unnoticed and unreported.”

48 HILLS Tell me a little bit about the piece — how many dancers are involved, and what shape does it take?

DAVID HERRERA “TOUCH” is a 60-minute work. The cast includes nine dancers, two commissioned musical composers, a commissioned writer/poet, a light designer, a costumer, and a set designer.

The piece is presented in a series of moments that highlight the experience of forced separation: togetherness of family (or community), the physical forced separation, the sense of being distanced, detached, and isolated, and lastly, the strangeness of reunification at the border fence.

In order to accomplish the desired effect it was decided that the set and audience layout was of utmost importance. To help audience members understand this event we wanted to ensure they would be immersed in the dance experience by bringing them directly onto the stage.

By doing so, this effectively breaks down the fourth wall effect a traditional theater setting presents. To push the boundaries of immersion and separation even further, we placed seats independently of one another throughout the stage, thereby making each seat its own island. Two additional visual set pieces, a transparent curtain and a border fence replica, will intensify the existing division among audience members.

48H How did the idea come to you, and how did you develop it for the performance?

DH In addition to the company’s own personal research and my family’s accounts, the production is supplemented by oral histories shared by the student member of IDEAS at UCLA. IDEAS (Improving Dreams, Equality, Access, and Success) is the official voice of undocumented students at UCLA, members of whom DHPCo. interviewed during the creative the process.

During one such interview, a student revealed that she is unable to establish and maintain lasting, intimate relationships (both romantic and platonic), the result of her mother’s absence during infancy. She recognizes her fear of attachment, choosing to be alone rather than deal with the potential loss of intimacy (e.g. having relationships taken away from her). After reuniting, she recalls viewing her mother as a stranger, hiding from her and crying when she tried to hold her. Even though she acknowledges her mother did not choose the separation, it still took her years to develop trust and establish security with her mother.

“I get sad… I avoid it as much as I can. I put it all inside a box and throw that box away,” stated another student who hasn’t seen his father in six years. He explained that he still does not feel comfortable speaking about his father who is unable to come to the country. Despite the challenges of growing up without his father, he recognizes the benefits and opportunities afforded to him by remaining in the U.S. As an immigrant, he too, is fearful of deportation.

These interviews were incredibly valuable, allowing DHPCo. to better understand the lasting impact of forced separations.

48H Can you share any more about your personal connection to this piece?

DH Having been born to immigrant parents, I do know first hand the day-to-day fears immigrants living within the US experience. I have memories from my childhood where on returns home from visiting my grandparents in Mexico my parents had to be smuggled back into the country via “coyotes.” My sister and I (both American-born) were told to cross and remain with family “friends” until we would be reunited with them hours and sometimes even days later.

I remember my parents speaking in hushed voices at night about “that person” who was deported. I remember the fear that overtook them when they would hear of another factory in Los Angeles being raided for “mojados.” The words “La Migra” terrified them.

Though my immediate family is no longer in danger, and the fear and shame are now distant memories, the experience came back into my family’s fold via my aunt’s experience several years ago. We witnessed as my aunt, my mother’s sister, was caught in the increasing I.C.E raids in the 2000s. Though she was going through the naturalization process at the time, she was still an immigrant and had to make the heartbreaking choice to stay a family unit and return to Mexico along with her American children or face being separated.

She reluctantly chose to take her kids with her to Mexico. Had she not her children would remain in the United States either adopted by another family member or face being scattered in the foster home system. If the children remained in the country they would be separated from her indefinitely.

48H In what ways do you think dance has a unique capacity to address these issues — issue like immigration reform and deportation?

DH As a dancer and choreographer, I rely on my body for communication. I truly believe that our bodies record our memories. From the tingling sensations of awkward first kisses, to the rage of anger, to the stomach aching sadness of losing a friend or family member, our bodies do indeed remember.

Dance has the inherent ability to speak directly to issues of forced separations as the phenomenon is a uniquely physical one. In the studio we worked on the ideas of body recall, the sensation of touch and its emotional capacities, and translating the stories shared with us into movement vocabulary.

We hope “TOUCH” will bring much needed awareness to the forced separation phenomenon affecting thousands of American and immigrant families. Dance being a physical and often times communal experience is primed to inform, engage, and activate our audience, via movement vocabulary and stage design, to think critically about the issues we present while making the subjects’ stories as tangible as touch itself.

TOUCH

April 2-4, 8pm, $20-$30

Z Space

450 Florida, SF.

Tickets and more info here.

Like this story? Please donate to help us write more like it.